Introduction

This campaign, executed by the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, covered almost all of the period of the Great War, from November 1914 through to the Armistice of Mudros on 30th October, 1918. No fewer than nine of our sixty fallen took part in this conflict. Throughout it was under-reported and the British public either knew little of the detail or simply viewed it as an unnecessary drain on military resources that could be better spent on the Western Front.

The conflict was similar to that in Mesopotamia”also a Cinderella’ campaign: the protection of British interests against threat from the Ottoman Empire which was backed by German and Austria. Both began to protect vital assets (Mesopotamia, oil and Egypt the Suez Canal) but expanded by mission creep into wider conflicts with high casualties from battle and illness.

At its inception, this campaign was restricted to Egypt”the conflict did not move north into Palestine until early 1917.

Background

Egypt was in a unique position at the outbreak of War. While it was nominally an autonomous vassal state of the Ottoman Empire, in practice it was under British control. The building of the Suez Canal, completed in 1869, left Egypt in crippling debt to European banks. In 1875 the debt burden forced it to sell its shares in the Canal to the British Government, leading to the imposition of British and French controllers who sat as part of the Egyptian Cabinet. The British controllers held the purse-strings and so became the power-brokers.

At the outbreak of War, the country was therefore compromised”an Ottoman territory controlled by the British. On 5th November 1918, Britain declared Egypt a British Protectorate. The Ottoman Sultan Abbas II was replaced by his uncle Hussein Kamel who was more amenable to British influence. The result was an Egypt that was neither fully ally nor independent. In practice, British and Commonwealth forces would have use of railways, ports and be able to use Egyptian workers, but there was no obligation on Egypt to give military aid. Britain would also be able to impose martial law on British and European residents and have authority to arrest and detain undesirable aliens.

Britain’s primary interest in Egypt lay in the Suez Canal, which was vital in simplifying logistics: supplies of men, oil and war materials from India, New Zealand, Australia and other Eastern colonies would be greatly hampered should this artery be cut.

This arrangement also gave Britain and its Commonwealth units much-need port and logistics facilities for the Gallipoli conflict, which was part of the Balkan Theatre of War.

Beginnings

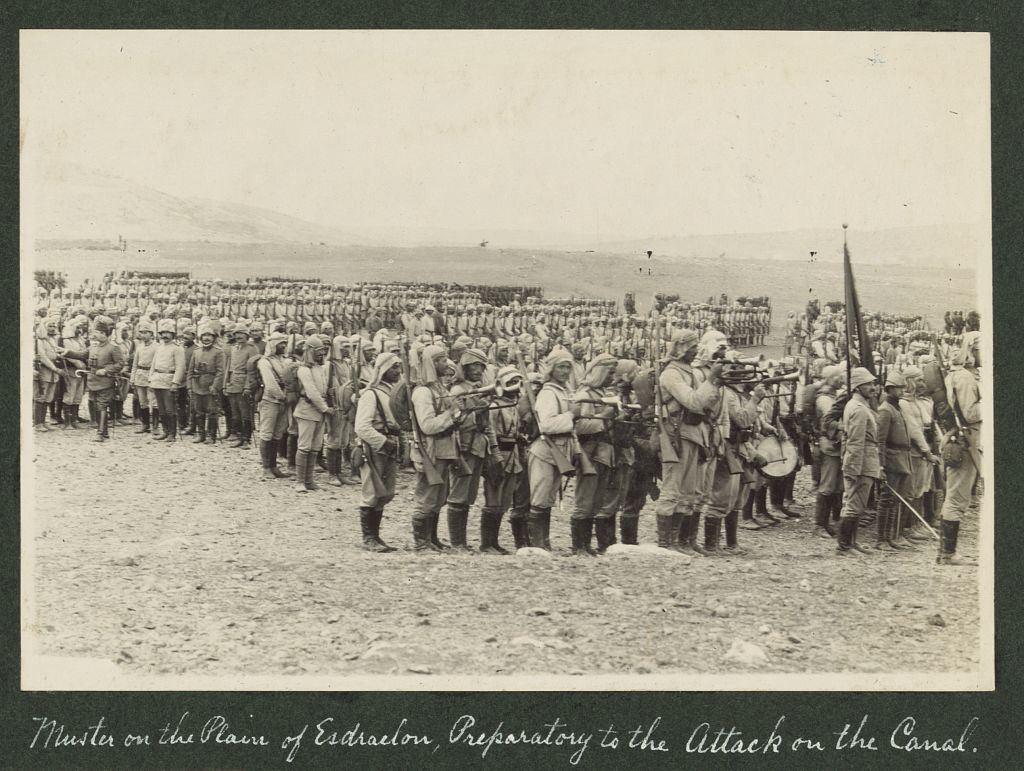

In the early phase, Ottoman forces assembled in Palestine preparatory to an incursion into Egyptian territory to disrupt or prevent use of the Suez Canal, with the first wave of attacks coming between 26th January and 4th February, 1915.

The defence of the Canal was initially in the hands of the 30,000-strong Imperial Service Cavalry Brigade, supported by Egyptian Army and Indian artillery. Sinai was largely undefended and the attacking Ottomans had a straightforward approach to the Canal from their territory in southern Palestine. In the first attacks, only two Ottoman Companies succeeded in crossing the Canal, and, broadly, the conflict quickly became one of warfare with two armies separated by the Canal. British and Commonwealth troops occupied the western side, and Ottomans the eastern shore. However, this allowed the attackers to disrupt any shipping passing through the Canal.

By the end of 1915 it had become clear that defending the Canal from the West Bank was impossible and the War Cabinet, following the advice of Lord Kitchener, authorised defensive lines to be moved across the Canal and at least 11,000 yards into the Sinai Peninsular. The buffer zone would keep the Canal safe from heavy artillery fire. An increase of men and equipment was also authorised to enable this and as a result shipping was again able to pass unmolested.

In December 1915, the ignominious ending of the Gallipoli campaign resulted in men and materials being withdrawn, much of it to Egypt, where, by early 1916, 400,000 infantry and cavalry were stationed. All resources were brought together under Sir Archibald Murray as a new Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF). While generally these troops provided and Army Reserve for all Theatres of War (including the Western Front), they provided the means to control Ottoman ambitions in Egypt.

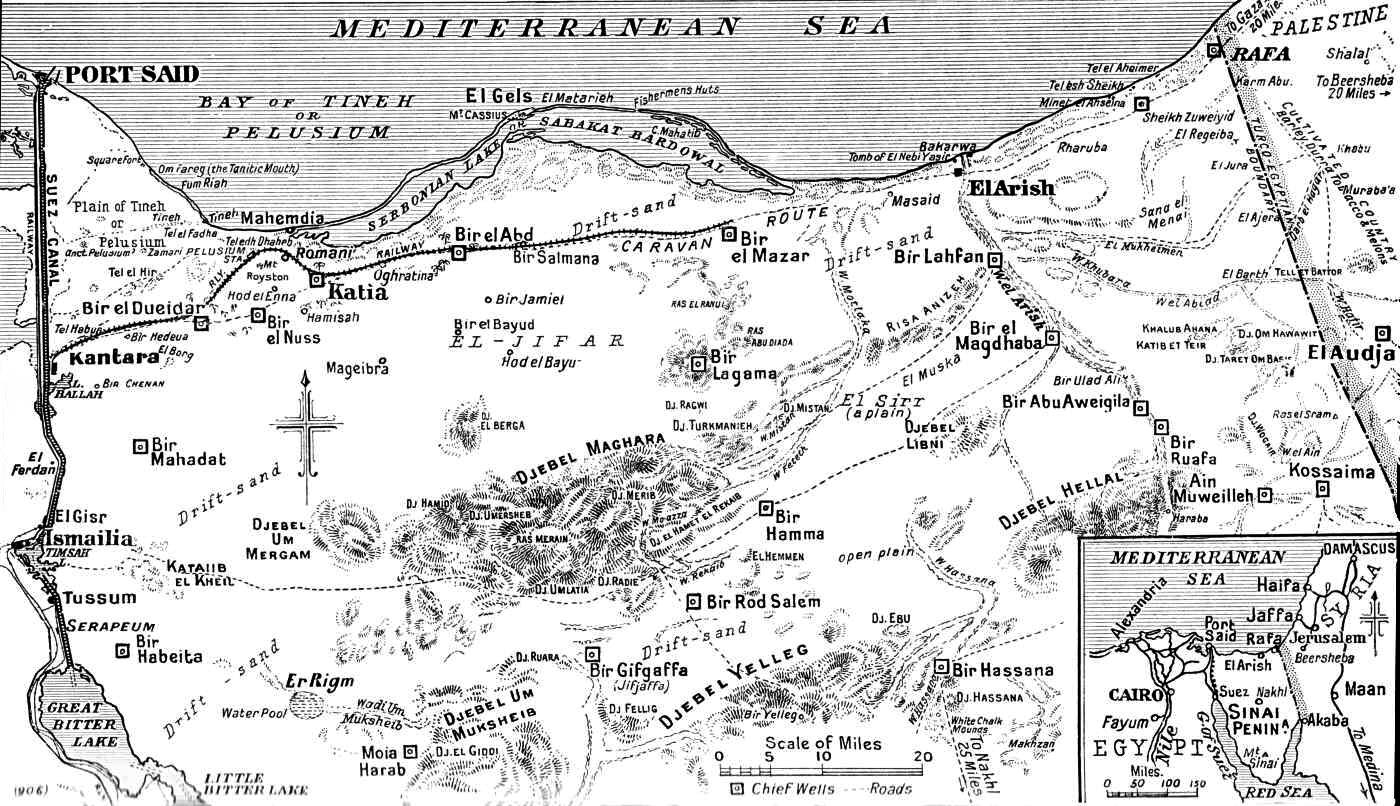

The Retaking of Sinai

Murray’s strategy was clear from the outset: a move to recover all of the Egyptian territory of the Sinai was more sustainable than maintaining the static defence line just east of the Canal. In particular, by controlling all oases in the peninsula, it would become a natural geographical barrier to further incursions if they were able to deny attacking troops access to water. The isolated wells and water cisterns of the interior were destroyed or drained rather than garrisoned and defended. This left central Sinai inhospitable and therefore only the northern coastal route needed to be defended. These actions, including the Raid on Jifjafa (April 1916) and the Battle of Romani (April/May 1916), were carried out with the assistance of Australian and New Zealand units. The clearing of Sinai had begun well, although troops from both sides suffered much from the Summer heat. The Ottoman response came in the form of sporadic raids and the use of aircraft to bomb British and Commonwealth positions. The Royal Engineers are particularly worthy of mention at this time, working tirelessly to provide railway and water pipelines across inhospitable terrain and ensuring that supply lines matched advances.

The clearing of Sinai was a staged campaign, with steady advances along the northern coastal route, taking Ottoman positions one by one and allowing supply lines to keep pace. There were few major battles, but those of Magdhaba (December 1916) and Rafa (January 1917) were the last, and mopping up operations concluded the securing of Sinai in February.

In parallel to the ejection of Ottoman forces from the peninsula, a second front opened up to the West. The Germans and Ottomans incited the Senussis”a Muslim sect in Libya and Western Egypt who, up to this point, had friendly relations with the British in Egypt”to declare jihad against British forces. There was also an unrealised hope that the Senussi uprising might draw Egyptian Muslims into conflict with what was effectively an occupying force. The conflict was small-scale, widespread and sporadic, confined to the Western Desert and Mediterranean Coastline. The Senussi numbers are difficult to esitimate but probably around 5,000-6,000 combatants.

Into Palestine

Knowing that operations in Sinai were coming to a succesful conclusion, Murray proposed to continue the momentum of the campaign and keep the Ottoman armies on the back foot. The War Office however, told Murray to consolidate, and ordered him to release his 42nd Division for action on the Western Front. Perhaps this cautious response was as a result of the lesson learnt in the disastrous headlong pursuit of the Ottomans in the Mesopotamia of over a year before (see special feature on the Mesopotamian Campaign).

Within six weeks this decision had been overturned. A Franco-British conference (Calais, 26th February 1917) decided that all fronts in all Theatres of War should push the enemy hard. Unfortunately for Murray, the turnabout came one week after the despatch of the 42nd Division, no further resources were made available, and he was told not to begin the advance into Palestine until 26th March thus losing the impetus of recent gains and the advantage of fighting an army in the chaos of retreat. While the hiatus gave opportunity for rest, equipping and further improvement of supply lines, it also gave the Ottoman forces time to strengthen its defenses in Southern Palestine. The garrison at Gaza in this short time was increased from a strength of 3,500 rifles to 10,500.

The First Battle of Gaza on 26th March, 1917, was an inconclusive affair. Anzac and Imperial forces made early gains, taking all objectives before withdrawal at nightfall. Had the Command better understood their daytime successes they may well have had continued success. As a result, the Ottoman defences remained largely intact and a stand-off ensued, during which time the defences of Gaza were further strengthened, as was the whole of the Ottoman line inland to Beersheba. Murray’s problems were exacerbated by his loose wording in reports sent back to England”these led to an assumption of victory and orders to advance to take Jerusalem. The Second Battale of Gaza took place from 17th to 19th April, with troops attacking across open ground towards the newly constructed defences. Losses were heavy for little gain. The result was a stalemate and an entrenched conflict more redolent of the Western Front. Despite a well-fought Suez-Sinai campaign, these setbacks and failures were sufficient to precipitate Murray being relieved of his command and recalled to England. His replacement was Bloody Bull Edmund Allenby.

It was not until November of 1917 that the stand-off was ended with what became known as the Third battle of Gaza. Perhaps this is a misnomer as the actions referred to are mostly of the dismantling of the defences around Gaza itself, and the defensive lines that ran inland to the southeast, ending at Beersheba. Beginning on 27th October, a heavy six-day bombardment”the heaviest of WWI outside Europe”preceded night raids on strategic defences. Scottish infantry played a large part in the successes of the attacks which were at some cost.

This morning, at 3 o’clock, I attacked the SW front of the Gaza defences. We took them; on a front of some 6000 yards, and to a depth of some 1000 to 1500 yards. We now overlook Gaza; and my left is on the sea coast, NE of the town. The Navy cooperated with fire from the sea; and shot well. We’ve taken some 300 prisoners and some machine guns, so far.

Allenby, letter to Lady Allenby, 1st and 2nd November, 1917

The combined use of land and off-shore bombardment, aerial bombing, and infantry attacks on defensive tranches and strongholds around Gaza continued until, on November 7th, the EEF was able to take the city itself with little opposition”the Ottomans had withdrawn and left it largely unoccupied. The day before, Allenby had predicted this would be the case:

We’ve had a successful day. We attacked the left of the Turkish positions, from N. of Beersheba, and have rolled them up as far as Sharia. The Turks fought well but have been badly defeated. Now, at 6 p.m., I am sending out orders to press in pursuit tomorrow. Gaza was not attacked; but I should not be surprised if this affected seriously her defenders. I am putting a lot of shell into them, and the Navy are still pounding them effectively.

Allenby, letter to Lady Allenby 6th, November, 1917

The whole of the defensive line from the Gaza on the coastal plain to Beersheba had been systematically dismantled and the gateway to Palestine now lay open to the EEF.

There was still some hard fighting ahead. The Battle of Nebi Samwill (17-24 November) led to the Battle of Jerusalem (17 November-9 December) and its capture. The surrender read:

Due to the severity of the siege of the city and the suffering that this peaceful country has endured from your heavy guns; and for fear that these deadly bombs will hit the holy places, we are forced to hand over to you the city through Hussein al-Husseini, the mayor of Jerusalem, hoping that you will protect Jerusalem the way we have protected it for more than five hundred years.

The Mayor of Jerusalem, Hussein Salim al-Husseini

Allenby made his formal entry into Jerusalem through the Jaffa Gate on 11th December, 1917. He did so on foot, eschewing the more dignified motor transport or horseback in deference to the holiness of the city. The scene is not empty theatre; its significance cannot be overplayed. For the Ottomans it inflicted huge hurt to its morale and identity, having previously lost the holy places of Mecca and Baghdad. To the Allied cause, it was a much-needed fillip at the end of a disappointing and draining year.

Allenby’s official proclamation, in response to the above surrender, made on 9 December 1917 reads as follows:

To the Inhabitants of Jerusalem, the Blessed and the People Dwelling in Its Vicinity:

The defeat inflicted upon the Turks by the troops under my command has resulted in the occupation of your city by my forces. I, therefore, here now proclaim it to be under martial law, under which form of administration it will remain so long as military considerations make necessary.

However, lest any of you be alarmed by reason of your experience at the hands of the enemy who has retired, I hereby inform you that it is my desire that every person pursue his lawful business without fear of interruption.

Furthermore, since your city is regarded with affection by the adherents of three of the great religions of mankind and its soil has been consecrated by the prayers and pilgrimages of multitudes of devout people of these three religions for many centuries, therefore, do I make it known to you that every sacred building, monument, holy spot, shrine, traditional site, endowment, pious bequest, or customary place of prayer of whatsoever form of the three religions will be maintained and protected according to the existing customs and beliefs of those to whose faith they are sacred.

Guardians have been established at Bethlehem and on Rachel’s Tomb. The tomb at Hebron has been placed under exclusive Moslem control.

The hereditary custodians at the gates of the Holy Sepulchre have been requested to take up their accustomed duties in remembrance of the magnanimous act of the Caliph Omar, who protected that church.

In an awareness which would not be out of place today, Allenby took great care to ban the use of any use of Crusader imagery or language, giving his Press Officers strict instructions to this effect. He always emphasised that the conflict was with the Ottoman Empire and not Islam.

The End Game

The campaign, however, was not yet finished. Lloyd George wanted the total defeat of the Ottoman Empire, which would free much-needed resources for redeployment to the Western Front.

Allenby’s and the EEF’s work continued: the Battles of Jaffa (21-22 Dec.), Jericho (February 1918), Turmus ‘Aya or Judean Hills (8-12 March), Berukin (9“11 April), Megiddo (19-25 September), Damascus (October), and Aleppo (October).

It was with the fall of Aleppo on 25th October 1918 that the Ottoman Government conceded defeat and signed an armistice at Mudros on 30 October, 1918. The full surrender followed two days later.

In Conclusion

The aim of redeployment of men to the Western Front had not been achieved or necessary as the European war was in its final throes. Yet, of all campaigns, this had proved perhaps the most successful. All goals”original and extended”had been achieved, efficiently and without having to divert major resources from other fronts.

Success in war always comes at a price. It is estimated that the Egyptian Campaign (Suez, Sinai and Palestine) accounted for over 85,000 deaths.

British and Dominions

12,873 killed or missing

5,981 died of disease

37,193 wounded

1,385 captured

Ottoman

25,433 killed or missing

40,900 died of disease

34,199 wounded

78,735 captured

We also remember those of our number who served and/or died in this campaign: A.O. Bartlett, F.W. Cook, G. Follett, R. Fulford, P.S.H. Grice, J. Pett, H.J. Payne, S.H. Seeviour, C.F. Wilson

Sources and Credits

Estimated casualty figures of Ottoman forces: Erickson, E. J. (2001). Ordered to Die: A History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War: No. 201 Contributions in Military Studies. Westport Connecticut: Greenwood Press, and Erickson, E. J., Gooch, J., and Reid, B.H. (2007). Ottoman Army Effectiveness in World War I: A Comparative Study. Cass Military History and Policy Series, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. Cited in Wikipedia (2018) Sinai and Palestine Campaign [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sinai_and_Palestine_Campaign#cite_note-393 [Accessed 14 May 2018].

Imperial War Museum (1917). General Allenby’s formal entry on foot to Jerusalem, Q 12616. [online] Available at: https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205194701 [Accessed 2018].

Library of Congress (1914). Muster on the Plain of Esdraelon: Library of Congress Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-ppmsca-13709, No known restrictions on publication. [online] Available at: http://memory.loc.gov/phpdata/pageturner.php?type=contactminor&cmIMG1=/pnp/ppmsca/13700/13709/00010t.gif&agg=ppmsca&item=13709&caption=9 [Accessed 13 May 2018].

Library of Congress (1917). Mosque of Gaza before the operations, 1917: Library of Congress Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-ppmsca-13709, No known restrictions on publication. [online] Available at: http://memory.loc.gov/phpdata/pageturner.php?type=contactminor&cmIMG1=/pnp/ppmsca/13700/13709/00129t.gif&agg=ppmsca&item=13709&caption=128 [Accessed 14 May 2018].

New Zealand History (2014). Map of Ottoman Empire in 1914. [online] Available at: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/map-ottoman-empire-1914 [Accessed 2018] Derived work by John Vickers 25 May 2018.

Wikimedia (2008) File:MapSinaiWWI.jpg [online] Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MapSinaiWWI.jpg [Accessed 14 May 2018].