Teaching And Training

The way teachers are trained has changed significantly over the years. To understand better the lives of our sixty alumni who died in the Great War, we should look at the profession they trained for at the turn of the twentieth century, and what their lives were like while they were studying at Winchester Diocesan Training College. The earliest of our students arrived at the College in 1899 and the latest started in 1914.

A Brief History

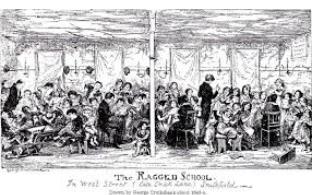

Education, for certain elements within society, has always been available in this country. The idea of education for all was a much later idea, as was a system of free education. Until the late nineteenth century all university fellows and many schoolmasters were required to be in Holy Orders. Schoolmistresses taught the basics in Charity, Dame and informal village schools ; many schools were funded by permanent endowments. Charity Schools provided education for poor students aged between 7 and 11. The Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge funded some of these Charity Schools and provided some of the early teacher training. The Sunday School Movement was another way that poor boys could gain a very basic education. These schools used the older boys to teach the younger ones, the fore-runner of the pupil-teacher system. In 1818 John Pounds started the first so called Ragged School teaching the three R’s to poor children without charging fees. After his death in 1839 other Ragged schools were set up around the country. Over the next eight years 200 free schools were established in Britain. It was generally accepted that the children of the poor needed an education solely in Holy Scriptures , the Catechism, reading and writing.

In 1811 the Anglican National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church in England and Wales was established. These schools became known as National schools. A monopoly in an Anglican education for the poor was prevented when Joseph Fox formed the non-conformist, non-denominational Society for Promoting the Lancasterian System 1 for the Education of the Poor. These became known as the British schools. These two terms were still in operation at the time our cohort of young teachers began their careers.

In August 1833 Parliament voted sums of money each year for the construction of schools for poor children in England and Wales. Scotland had implemented a similar programme in the seventeenth century. In 1839 Government grants for construction and maintenance of schools was switched to voluntary bodies and then became conditional upon a satisfactory inspection.

The 1870 Forster Elementary Education Act required that Board Schools be set up to provide Primary education in areas where the existing provision was deemed inadequate. These schools were fee-charging but poor parents could be exempted. These schools were managed by elected school boards. The 1880 Elementary Act insisted on compulsory attendance for children aged between five and ten. In 1891 the Elementary Education Act provided for state payment of fees, up to ten shillings per child. Later acts raised the leaving age first to 11 and then to 13.

Schools at the Turn of the Twentieth Century

When the Winchester Diocescan Training College students had finished their training there was elementary educational provision for all children, regardless of their family income. Most of the students who were teaching by the time of the 1911 census are recorded as working in County Council schools. The 1902 Balfour Act ended the divide between schools run by school boards and church schools. Local Education Authorities were established and the school boards disbanded. Funds were provided for denominational religious instruction in voluntary elementary schools owned primarily by the Church of England and Roman Catholic Churches. This Act alienated the non-conformist churches who were given no such aid or consideration. Church schools were now obliged to meet the same standards as other types of school.

Pupil – Teacher Scheme

Before the Education Act of 1902 the training of teachers was largely carried out under a pupil-teacher system. The first pupil-teacher scheme was set up in a Poor Law School in Norwood by Dr. J. Phillips Kay (later Kay-Shuttleworth). In 1846 a national pupil-teacher scheme was launched for carefully selected, mainly middle-class, Elementary School pupils aged 13 or over. These pupil-teachers had to fulfil certain scholastic, moral and physical conditions. The scheme worked as an apprenticeship, a pupil meeting the criteria would be apprenticed to a selected headteacher for five years. They would teach throughout the day and be taught by the headteacher before or after school for at least one and a half hours a day, for five days a week. Every year they were required to be examined by an HMI. Pupil-teachers were paid: a boy would receive £10 per annum for his first year, by the end of their fifth year they would be receiving up to £20, with a girl receiving two- thirds of that. The headteacher would be paid for their teaching and supervising role, £5 for one pupil-teacher, £9 for two, but this was dependent on the inspection of the student being satisfactory. A headteacher was allowed one pupil-teacher for every 25 pupils on the school roll. When the apprenticeship had been successfully completed the pupil-teacher would receive a certificate which would enable him or her to sit the examination for the Queen’s Scholarship. This would qualify the holder for a place in a training college with a maintenance grant of £25 for men or £20 for women. Some pupil-teachers, having completed their apprenticeship, were not in a position to delay earning a wage. They could take up a teaching position in a grant-aided elementary school as an Uncertified Teacher. Training College students who successfully completed 1, 2 or 3 years of training would be awarded the Teachers’ Certificate. On Census returns the terms Assistant or Uncertificated teacher are often seen. Uncertified or Uncertificated Teacher would be used for teachers who had completed their pupil-teacher apprenticeship but had not done their Teaching Certificate, Assistant Teachers were working the two years required after completion of training before they were finally awarded their certification. The term Assistant Teacher also seemed to be used in other circumstances, for example for a teacher who wasn’t the Headteacher, and sometimes for an Uncertified Teacher, which adds an element of uncertainty when trying to interpret historical documents.

The decade after 1870 saw a near trebling (from 12,467 to 31,422) in the number of certificated teachers, a more than doubling (14,612 to 32,128) of pupil-teachers and a large growth in the number of Assistant or Uncertificated teachers from 1262 to 7652. Within a few years the number of Uncertificated Teachers was beginning to exceed the number of Certificated ones in certain areas, as they were considerably cheaper to employ.

Pupil-teachers began their apprenticeship at 13 and after 5 years entered a training college. When established as a schoolmaster, possibly at £50 per year, with a house and additional payments for any pupil teachers in his care and sometimes children’s attendance money, the pay and future prospects of a schoolmaster were considerably improved. Students were encouraged to complete two full years at college in which time they could not only achieve a level of academic attainment but also professional competency.

In the latter part of the nineteenth century the age to begin training as a pupil-teacher was raised to 14, and then at the turn of the century it was raised again to 15. There were exceptions made to this age limit, particularly in rural areas. To be accepted as a pupil-teacher the young students needed to be approved by an HMI, pass a medical, and an examination set by the Board of Education in Reading and Recitation, English, History, Geography, Arithmetic, Algebra, and Euclid (boys) or Needlework (girls) and Teaching. Pupil-teachers were not allowed to teach for more than 5 hours a day or 20 hours a week. They were examined annually by an HMI. After their period as a pupil-teacher came to an end they could sit for the Queen’s (King’s from 1901) Scholarship. A first or second class pass would qualify the student to enter a training college although this did not guarantee a place as applicants were far more numerous than places. In 1900 barely 44.5% of pupil -teachers were accepted.

From 1902 regulations for pupil-teacher training were tightened up and all potential future teachers were encouraged to get a good secondary education wherever possible. In 1906 King’s Scholarships were abolished. From 1907 there was instead, a Preliminary Examination for the Elementary School Teachers’ Certificate’. This examination was in two parts, compulsory subjects in Part 1 needed to be passed before continuing onto the second part. In Part 2 there were compulsory subjects English, History and Geography, but also a wider range of other subjects from which the student could choose three options, from within the categories of Elementary Science, Elementary Mathematics, and Foreign Languages. Also from 1907 there was an alternative route into the profession apart from being a pupil-teacher. Selected pupils at secondary school could be awarded bursaries to enable them to stay at school for an additional year. They could then enter training college or serve in a school as a student teacher for up to a year and then enter college. From August 1909 the Board of Education would only consider applicants who had been to a recognised Secondary School for at least the previous three years and would only pay a grant to Bursars who passed (either during their bursary year or within one year after completion of it) one of the exams qualifying them for entry to a Training College. Bursars could be accepted at a Training College at 17, a year younger than those following the pupil-teacher system. There was criticism of the new system by some who considered it to be unfair to children from working class families who were not in a position to delay earning a wage until they reached the age of 20 or 21. By the outbreak of the Great War the old pupil-teacher system was more or less obsolete, although it was not formally disbanded until the nineteen thirties.

Teacher Training and Training Colleges

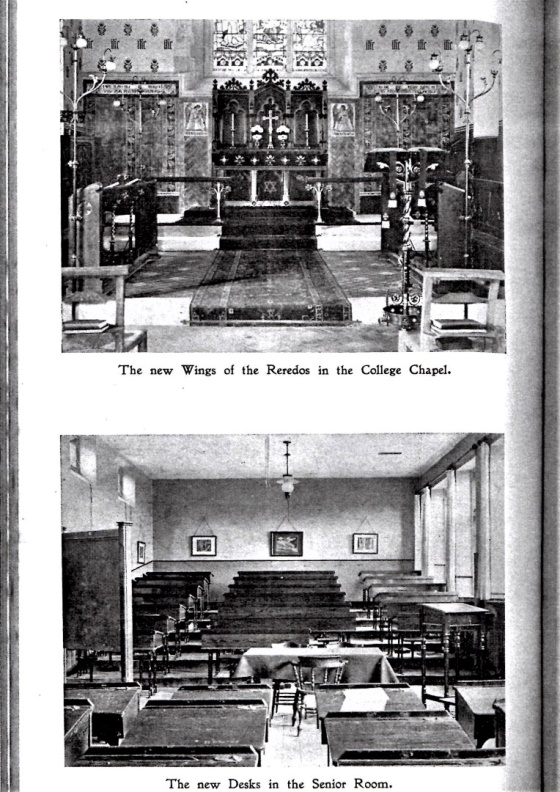

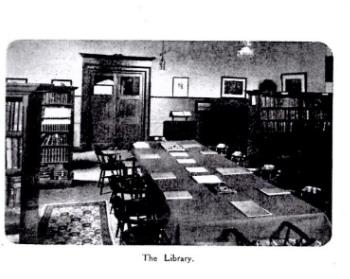

The first training colleges for teachers were set up in the first half of the nineteenth century. The Nonconformists developed the first training school for teachers, based on a monitorial system. This training was aimed exclusively at training teachers for elementary schools. In August 1840 the Winchester Diocesan Training College was opened. By 1850 there were 30 such institutions of which all but five were associated with the Church of England. This is not surprising as the primary purpose of education for the poor was to provide religious instruction. Religious controversy dogged much of the early training courses, as it did across educational provision in general. Many of the groups that founded the early colleges saw teachers as Christian missionaries, bringing enlightenment to the uneducated masses. Church Colleges were criticised for their rather limited curriculum in secular subjects. The 1870s curriculum included Holy Scripture, the Book of Common Prayer, English, grammar, Latin, Economy, reading and repetition, mathematics, French, Music, Drawing, gardening, Science (heat, light, acoustics).

The early colleges were almost all residential and small, with a maximum of 100 students, and conditions in these institutions were poor. Most courses were short, with almost half of them lasting a year or less. Universities became involved in the training of some teachers in 1890 when Day Training Colleges’ attached to the universities were established. At the turn of the century it was recognised that if the standard of teaching in schools were to improve, then the first step would need to be improving the educational standard of those going into the teaching profession. In 1902 the training of teachers was recognised as a form of higher education, which enabled the new L.E.A.s to make Secondary Schools available for the training of pupil-teachers. The 1902 Education Act also allowed Local Education Authorities to provide and maintain Training Colleges to help meet the demand for places. In 1904 Municipal Training Colleges were recognised, and it was decided that pupil-teachers must be at least 16 years of age and should have spent three to four years being educated in a Secondary School. From 1904 the Board of Education allowed Local Education Authorities to get involved with providing teacher training. The following year building grants became available to L.E.A.s to encourage the provision of Training Colleges.

Conditions for the students in Training Colleges were variable. At a time of economic depression and cut backs, allied to the relatively low status of teaching as a profession meant that standards were often at best mediocre and in some cases completely inadequate. In Winchester in 1858 at the time when the Training College was situated in Wolvesey, the Bishop’s Palace , the Board of Education decided that it was necessary to investigate the sanitary conditions at the College. There had been outbreaks of cholera and typhus as well as a rat infestation. Wolvesey Palace was downstream of the city of Winchester, the river acting as a sewer as it carried effluent towards both the Palace and Winchester College, the Public School.

Many of the early Colleges were modelled on Battersea Normal School, which had been established in 1841. In 1846 the Committee of Councils minute began the system of paid pupil-teachers and established Queen’s Scholarships which would pay the greater part of the student’s fees. Successful scholars had the opportunity to attend a Training College for two or three years. A system of examinations brought incremental funding to the Training Colleges, dependent on how well the students performed. In addition to this, the salary of a qualified teacher could be supplemented by as much as £100p.a. by the Council.

| Monday, Tuesday, Thursday & Friday | Sunday | |||

| 6.15 | Reveille sounded by the ringing of a handbell | 6.15 | Reveille sounded by the ringing of a handbell | |

| 6.30 | Cup of cocoa in the dining hall | 6.30 | Cup of cocoa in the dining hall | |

| 6.45 | Roll call followed by an hours lecture, then morning service | 6.45 | Roll call followed by an hours lecture, then morning service | |

| 8.30 | Breakfast | 7.45 | Holy Communion optional | |

| 9 – 10.45 | Lectures | 9.00 | Roll call followed by an hours Scripture study | |

| 11 – 13.00 | Lectures | 11.00 | Matins with sermon | |

| 13 – 14.00 | Lunch | Afternoon free

|

||

| 14.00 | 2hr art/psychology/hygiene or criticism lesson | |||

| 14.30 | Time allocated to sport | |||

| 17.00 | Tea | |||

| 19.00 | Roll call followed by supervised private study in either the junior or senior lecture rooms | 19.00 | Evensong elsewhere in the city. (Seniors were allowed to miss evensong provided they went to a service) | |

| 21.15 | Evening chapel followed by supper | |||

| 21.30 | Bed | |||

| 22.30 | Lights out | |||

Wed and Sat

The timetable varied to allow for matches to be played, selected teams were excused study at noon, the rest of the students did Swedish Drill or Company Drill or rifle cleaning or brassing up’ in the Armoury. The afternoon was free until 7pm then debates or smoking concerts.

Grace was sung before and after every meal.

On entry to Winchester Diocesan Training College students signed a register which includes this statement:

“We do hereby sincerely declare that this our intention and our desire if admitted to Winchester Diocesan Training School to continue our period of training at this institution to the end of our second year and thereafter mindful of the advantages conferred upon us on our training to follow the profession of a schoolmaster at least until we have obtained our certificate.”

The certificate was awarded after they had taught for their first two years in the same school.

Practicing Schools

Each training college was allied with one or more schools in the local area where the students could practise their teaching skills .When the College was at Wolvesey Palace St. Michael’s was the practising school. Students attended St. Michael’s every Monday afternoon between 2-4pm. In the last four months of their training they were required to attend every afternoon. Later by the time college was on the West Hill site the main Practising’ school was St. Thomas’, but others including some in Eastleigh were added at a later date. Students were given regular access and teaching experience within these approved practising schools. Their teaching was supervised, they also had the opportunity to study good models of teaching within those schools and additionally they had lectures on the principals of teaching and the application of those principles. It is probably then safe to assume that those students who were employed in a practising school on completion of their studies were deemed to be particularly good teachers.

A student, writing in the college magazine, the Wintonian, in 1908, tells us about their experience of teaching practise:

Some members of the year have started their practical teaching at the Practising School. This is a pleasant time to which the remainder have to look forward. It entails a greater amount of work than ordinary life at College, especially in the preparation of lessons in the evening. Several have already experienced the great strain that is made on the vocal organs, particularly those who rely on a loud voice to preserve discipline in the class. As this part of our work here is of the highest importance, we are pleased to see the energy and interest displayed in it.

On a Lighter Note

The bond we share with past students of Winchester Diocesan Training College is not only about the place but also the profession we chose. By the time we began our teaching careers in the 1970s much had changed in the way we trained and what we could expect when we took up our first job in the classroom. The same can be said of the teacher training students today when they look back at what it was like for us. One aspect of the job that appears not to have changed, however, is that we will all have had an occasional disagreement with a parent!

From the Middlesex Chronicle, January 1914, a report of an incident at the school in Whitton where Christopher Burt, one of our Fallen alumni taught.

Mary Cowley (30) of Park Place, Hounslow Road, Whitton, was charged on a warrant at the Brentford Police Court on Tuesday…with disobedience to a summons for refusing to leave the schools when requested to do so by Mr. H.E. Brown, the head-master…the defendant came to the school and demanded to know why her child had been caned. He explained that the child had been late 13 out of a possible 14 times. She said If you cane my child again I’ll come down and **** cane you, or get my husband to do it. Witnesses requested her to leave the premises and she refused to do so, saying that she would not go away for any **** thing like him. As she still refused to go away witnesss sent for a police constable, whereupon she said The policeman won’t interfere with me because I’m a teetotaller, and that’s something to go on with, you ginger headed ****. … The Chairman told the defendant that if she had any complaint she ought to have made it in the proper manner…She would have to pay 5s or go to prison for three days.

Researcher and Author: Dee Sayers

Footnotes

- Named after Joseph Lancaster

Sources

British Newspaper Archive (1914). Middlesex Chronicle – Saturday 10 January 1914, p.7. [online] Available at: www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk [Accessed 2018].

Fikr (2012). Blackboard in Victorian school room at Ragged School Museum London. [online] Available at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/europealacarte/7838358508 [Accessed 2018].

James, T. (2015). The University of Winchester 175 Years of Values-Driven Higher Education. London: Third Millennium.

Keating, J. (2010). Teacher training “ up to the 1960s [Word document] Available at: https://www.history.ac.uk/history-in-education/sites/history-in-education/files/attachments/teacher_training_-_up_to_the_1960s.doc [Accessed 2018].

Rose, M. (1981). A history of King Alfred’s College, Winchester 1840-1980. London: Phillimore.

Wikimedia (2009). File:The Ragged School In West Street, late Chick Lane, Smithfield, by Gorges Cruikshank.jpg [online] Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Ragged_School_In_West_Street,_late_Chick_Lane,_Smithfield,_by_Gorges_Cruikshank.jpg [Accessed 2018].

| University of Winchester Archive “ Hampshire Record Office | ||

| Reference code | Record | |

| 47M91W/ | P2/4 | The Wintonian 1899-1900 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/5 | The Wintonian 1901-1902 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/6 | The Wintonian 1903-1904 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/7 | The Wintonian 1904-1906 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/8 | The Wintonian 1905-1907 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/10 | The Wintonian 1908-1910 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/11 | The Wintonian 1910-1914 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/12 | The Wintonian 1920-1925 |

| 47M91W/ | D1/2 | The Student Register |

| 47M91W/ | S5//5/10 | Photograph of 5 alumni in Mesopotamia |

| 47M91W/ | Q3/6 | A Khaki Diary |

| 47M91W/ | B1/2 | Reports of Training College 1913-1914 |

| 47M91W/ | Q1/5 | Report and Balance Sheets 1904- 1949 |

| 47M91W/ | R2/5 | History of the Volunteers Company 1910 |

| 47M91W/ | L1/2 | College Rules 1920 |

| Hampshire Record Office archive | ||

| 71M88W/6 | List of Prisoners at Kut | |

| 55M81W/PJ1 | Managers’ Minute Book 1876-1903 | |

| All material referenced as 47M91W/ is the copyright of The University of Winchester. Permission to reproduce photographs and other material for this narrative has been agreed by the University and Hampshire Record Office. | ||