Kut Al Amara 1915-16

The Forgotten War in Mesopotamia

Winchester Training College and the 1/4th Battalion of the Royal Hampshire Regiment

Dedicated to the memory of the 14 Alumni of Winchester Training College who lost their lives by

warfare, hunger, disease or mistreatment in Mesopotamia and Anatolia during the Great War

Their Name Liveth For Evermore

Introduction

Most people have heard of the Somme, Passchendaele and Verdun but fewer have an understanding of the events that centre on Kut el Amara in Mesopotamia. It has not been my intention to write a comprehensive history of the campaign in Mesopotamia but rather to attempt to relate the parts of the story that are of most relevance to the men of Winchester Training College. Many alumni of the College enlisted in the Hampshire Regiment because of their prior connections to the Regiment, through the Volunteer Company and later Territorial Company that was an integral part of their lives whilst undergoing their teacher training, but also because many were from the local area or chose to settle close by. Their choice of Regiment led them to serve in a theatre of war far from home, in a campaign that has been overshadowed by events happening elsewhere.

Why Mesopotamia?

The primary reason for the war in Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq) was oil. The Navy was largely dependent on oil-fired ships. It was imperative to control the oilfields and pipeline. The threat from Turkish interference with our influence over the Arabs in the area was also a factor. Having spent many years building relationships it was feared the local Arab leaders would be threatened, or worse, won over. Geographically, the area was of huge strategic importance, particularly in its proximity to India. German influence was increasing in the Persian Gulf and was seen as a potential threat to British interests.

Due to the scale of concurrent commitments on the Western Front and later in the Dardanelles, this campaign was initially left largely to the British Indian Army, with a consequent insufficiency of high-level direction and support from London. The official Hampshire Regiment history states that the campaign provides an excellent example of the difficulties of confining a side-show to its original purpose, even if that has been purely defensive and indeed necessary to prevent an enemy from attacking some vulnerable point. Once Turkey had come into the war we could not ignore the danger of her attacking the Persian oil fields from Mesopotamia, or fomenting trouble on the inflammable North West Frontier.

The Campaign

The Allied Army initially comprised the 6th (Poona) Division, under the command of Major-General Charles Townshend, later strengthened with the addition of the newly-formed 12th Division under Major-General George Gorringe and the 6th Cavalry Brigade commanded by Major-General Sir Charles Melliss VC.

The first objective was to secure the port of Basra and thereby access to the Shatt al-Arab waterway. This was achieved by the end of November 1914. The initial success prompted suggestions of an advance all the way to Baghdad. There were good reasons to be cautious but most were ignored. An initial advance was made to Qurna (Kurna), which was captured on 9th December 1914. Although more troops had been provided, other crucial support elements necessary for a deeper mission, in particular medical support, were not increased. Between December and the following April, Turkey strengthened the number of troops in the area. They unsuccessfully attacked the British at Shaiba. The British, however, took their victory at Shaiba as a sign of Turkish military ineffectiveness. A second threat to the oil supply came at Ahwaz, but the enemy withdrew before contact was made.

The Allies advanced through May 1915, to Amara (NB a different settlement Kut al Amara). Warnings were forthcoming from London that a presence at Amara would need to be sufficiently well-garrisoned and provisioned to protect it from an attack launched from Baghdad. The flooding of the Tigris, which resulted in waterlogged ground, combined with extremes of heat and dust, and the irritation of swarms of flies, were an ominous forewarning of the conditions that the troops would have to endure throughout this campaign.

It was this part of the campaign that saw the birth of Townshend’s Regatta, a variety of water borne forms of transport used to mount an assault on the enemy. The attack on Amara was another success and the troops continued their advance. Each new objective was justified as necessary to protect the previous captured objective, whereas in reality, once Qurna and Amara were held, it would have been relatively easy to defend Basra.

An attack was also made at Nasiriya, on the river Euphrates west of Qurna, in order to protect Basra from a flanking manoeuvre, and cost many British casualties. The Turks were positioned on either side of the Euphrates, about 6 miles south-east of Nasiriya. Approaches were marshy, making manoeuvring of the boats difficult. The first assault on 14th July failed, and another attempt was made on 24th July. The 1/4th Hampshires were in the thick of the fighting, in temperatures reaching 110 Fahrenheit in the shade and extreme humidity. The Turks eventually withdrew and Nasiriya was occupied on 25th July 1915. Captain Wilson reported, “After the battle, as after the preceding engagement, I spent some hours assisting in the evacuation of the wounded. I was horrified at what I saw, for at every point it was clear that the shamefully bad arrangements arose from bad staff work on the part of the medical authorities, rather than inherent difficulties. The wounded were crowded on board to lie on iron decks that had not been cleaned since horses and mules had stood on them for a week. There were few mattresses.”1 British casualties were 104 killed and 429 wounded.

Private Godfrey Wootton of 1/4th Hampshires died of wounds, 24th July 1915, buried in Basra, Iraq.

Pressure was immediately applied to advance to Kut-al-Amara. Major-General Townshend expressed concern, not about an advance on Kut, but on where the operation would end. On the 27th September the assault began. The advance was hampered by a number of factors: the ground was marshier than had been expected, the Turks occupied positions with good lines of fire and had constructed a boom to make progress up the Tigris difficult, and the advancing forces were struggling to get accurate positions of the enemy because of mirages and constantly blowing sand. The attack was successful despite these problems, and by the end of the following day the Turks had been driven from their positions. An attempt to follow and destroy the capability of the Turks failed and they were able to regroup.

More troops were sent to bolster the force, and against the advice of some, the order was received to advance on Baghdad. The 6th Division advanced to Ctesiphon (pronounced Tesiphon, but named Pistupon by the British troops), a mere 18 miles from Baghdad, winning minor engagements on the way. The Turks had however reinforced their position. The Battle of Ctesiphon began on 22nd November 1915. There were many casualties on both sides, with very little ground taken by the British. Townshend’s force withdrew, ostensibly to resupply, wait for reinforcements and evacuate the wounded. Medical arrangements were once again wholly inadequate. Townshend’s force withdrew to Aziziya and then the decision was made to continue back to Kut, via Umm-al-Tubal, and this retreat was begun, pursued all the way. They reached Kut-al-Amara on 3rd December 1915. Both sides considered they had been victorious at Ctesiphon, the Turks, for halting the British advance on Baghdad and the British for the heavy losses they had inflicted on the Turks.

By the time they arrived at Kut the British troops had marched 44 miles in the last 36 hours. They were in need of rest and replenishment. There were supplies there that had been stockpiled for an advance on Baghdad (see image below), and reinforcements were expected to arrive within the month. The decision was made to stand at Kut and to defend the town.

Townshend communicated with his troops:

I intend to defend Kut-al-Amara and not to retire any further. Reinforcements are being sent at once from Basra to relieve us. The honour of our mother country and the Empire demands that we all work heart and soul in the defence of this place. We must dig in deep and dig in quickly, and then the enemy’s shells will do little damage. We have ample food and ammunition, but commanding officers must husband the ammunition and not throw it away uselessly. The way you have managed to retire some 80 or 90 miles under the very noses of the Turks is nothing short of splendid, and speaks eloquently for the courage and discipline of this force.2

The Siege

7th December 1915 — 29th April 1916

Kut stands on a peninsula roughly 2 miles long and 1 mile wide within a horseshoe bend of the River Tigris. The population was about 7,000, mainly Arabs, the majority of whom stayed in the town for the duration of the siege. Relief was then expected to arrive quickly, which was a factor in the decision to allow the native population to stay. It was a decision based mainly on humanitarian concerns as winter weather was about to set in, but it had a huge impact on the availability of food supplies for the troops. 20,811 people were trapped in the town, some of those sick and wounded, with an estimated fighting capability of around 13,000.

The first task was to strengthen Kut’s defences, and it should be noted that although there were only meagre resources with which to defend the town, and despite determined attacks, it was never taken by the Turks. The troops inside Kut were subjected to shelling, sniper fire, and aerial attack. There were attempts at ground assaults on the frontline trenches, particularly in the early stages, when the British losses were between 150 and 200 each day, but the Turks soon learnt that their best form of attack was to enforce the siege and starve them out. On Christmas Eve and Christmas Day 1915, there were repeated attacks, which succeeded in breaching the British first line of defence, only to be driven back within hours. The Turks suffered heavy casualties, many of whom were within easy reach of the British lines. Attempts by British soldiers to recover the Turkish wounded were met with intense fire from the enemy and in the end the only assistance that they could offer was to throw food and water bottles to them. The stench from decomposing bodies can only be imagined as the siege continued. There were few serious attempts to overrun Kut after this although the shelling, sniper fire and aerial bombardment continued unabated.

Major-General Townshend believed he had enough food to feed the troops and the local population, but that belief was based on the assumption that relief would arrive relatively quickly. No one in the early stages seemed to have an idea just how much food there was, as estimates for how long it would last changed frequently. Food supplies were regularly pilfered. By the end of the siege, the troops were chronically malnourished, with fifteen soldiers a day dying, many of those from starvation. Fresh meat ran out towards the end of December 1915, and half rations were introduced in mid-January. The decision was made that the oxen and horses would have to be slaughtered to add to the larder. Many Indian troops believed the eating of horseflesh to be against their religion. Without meat their health suffered even more than the rest of the soldiers. They were given dispensation to eat the horsemeat from their religious leaders but even so many were reluctant. Supplies were augmented by pies made from starlings, sparrows and occasionally partridge and mud fish. Thankfully, fresh water was available from pump houses and collected rain water. Despite their best efforts however, the Force inside Kut was slowly starving to death, and disease was rife. By mid-February food supplies were worryingly low. The bread allocation was 12 ounces daily and meat 8 ounces. This ration was to be cut again before the end of the siege. The horses were also suffering from lack of food, with reports of them eating their own tails and blankets. The hospitals were growing crowded with most men suffering to some degree from scurvy, malaria, gastroenteritis, diarrhoea, dysentery and pneumonia. Decreasing rations had an inevitable effect on morale.

The supply of ammunition was adequate throughout the siege, partly due to the lower than anticipated frequency of Turkish direct attacks. Troop morale was good to begin with but as conditions deteriorated, naturally it was harder to maintain a positive attitude. Lice were a constant irritant and increasingly a worry as they were carriers of typhus. Men were able to de-louse themselves by stripping to the waist and laying out greybacks3 on the parapets of the trenches; thus ridding themselves of irritating and loathsome pests which were literally baked in the sun. Even so, many suffered terribly from septic sores.4

The physical conditions endured by the troops in Kut were described by Major Barber:

But it is the way of the East to provide every season with its special pest wherewith to irritate and chide its human guests. If it be not lice, then it’s fleas, then mosquitos, or in addition thereto, the sand-fly is provided. If a much-prayed-for wind springs up and blows them away, it brings with it a dust-storm and chokes you, or it blows so swiftly over a sun-baked desert that it scorches you and heats you till your head is like to burst. And if for some unaccountable reason none of these pests is in the ascendant, there is always the snake, the centipede, or the scorpion to fall back upon. And over and above all is the common fly, to whom, I suppose, in his myriads, pride of place should be given, for his numbers in the East sometimes are almost incredible to those who have not experienced him, and his persistence wears one out.

Barber Major C.H. Besieged in Kut and After (1917) quoted by Crowley p88.

The medical staff worked under appalling conditions. The hospital roof leaked, which was not ideal in the rainy season. Captain Mousley commented:

The only advantage to be derived from being in hospital here is that one has facilities for dying under medical supervision. Not that the authorities don’t do all they can…

Mousley Captain E.O. The Secrets of a Kuttite (1922) p85.

Minor conditions and wounds that would be treatable in a fit man became a real problem for the now seriously malnourished soldiers.

In the winter weather, men were frequently soaked by heavy rain, and it was freezing cold by night. The flooding river forced many to stand for long periods in trenches half full of water but they still did their best to maintain morale. The rainy season caused large parts of the town to flood. When the weather eventually began to improve, a dyke was built to help protect from further flooding. Eventually the weakened state of the men prevented much physical work.

As further relief efforts failed and with food supplies running out, the remaining guns and munitions were ordered to be destroyed and any useful equipment put out of action. On 29th April 1916 Halil Bey (the Turkish Commander), was informed that the garrison was ready to surrender. Townshend had in his command 13,309 personnel. During the siege 1,025 had died from enemy action, 721 from disease, 2,500 were wounded, 72 were missing, 1,450 were in hospital and of those the worst 1,130 were suggested to be exchanged with Turkish prisoners and evacuated down river to the relief force (although the final number was much lower). Of the large civilian population at the beginning of the siege, some had escaped, 247 had died and 663 were wounded.

The Relief Effort

There were several attempts to reach the besieged forces in Kut. The first began on 4th January 1916. An advance was made up the Tigris to Shaikh Saad. Speed was of the essence as the belief at this stage was that Kut would soon run out of food and this led to risks being taken and an under-prepared force being sent out.

On the 9th January Shaikh Saad was occupied by the British but the battle had taken a heavy toll. The speed of the advance on Shaikh Saad had outpaced the medical support, and the weather conditions did not help. The wounded travelled back to Basra by boat. Major Carter of the Indian medical services watched them arrive:

The stench that arose from its human cargo and its soiled boards baffles description. The patients were crowded and huddled together, and only a few could stand, others had to kneel to get out of the filth in which those lying flat on their backs were covered, some with blankets, some without. With no protection from the sun or rain for 17 days, with fractured limbs, many with their skins perforated in five or six places by broken bones, they had been left unattended writhing in the cramped space allowed them on the deck of the ship, which was covered with dysentery and swarming with flies and vermin.

Quoted in Neave D.L. Remembering Kut (from Vincent-Bagley evidence)(1937), re-quoted Crowley p76.

The next objective was an area known as The Wadi. The troops had just come through a very difficult engagement with the enemy and were exhausted, but the pressure was on to continue towards Kut. The Wadi fell to the British on the 14th January. The Turks abandoned their positions and withdrew to the Hanna defile (Umm-al-Hannah). Between 18th and 20th January the Relief Force got into position to attack there.

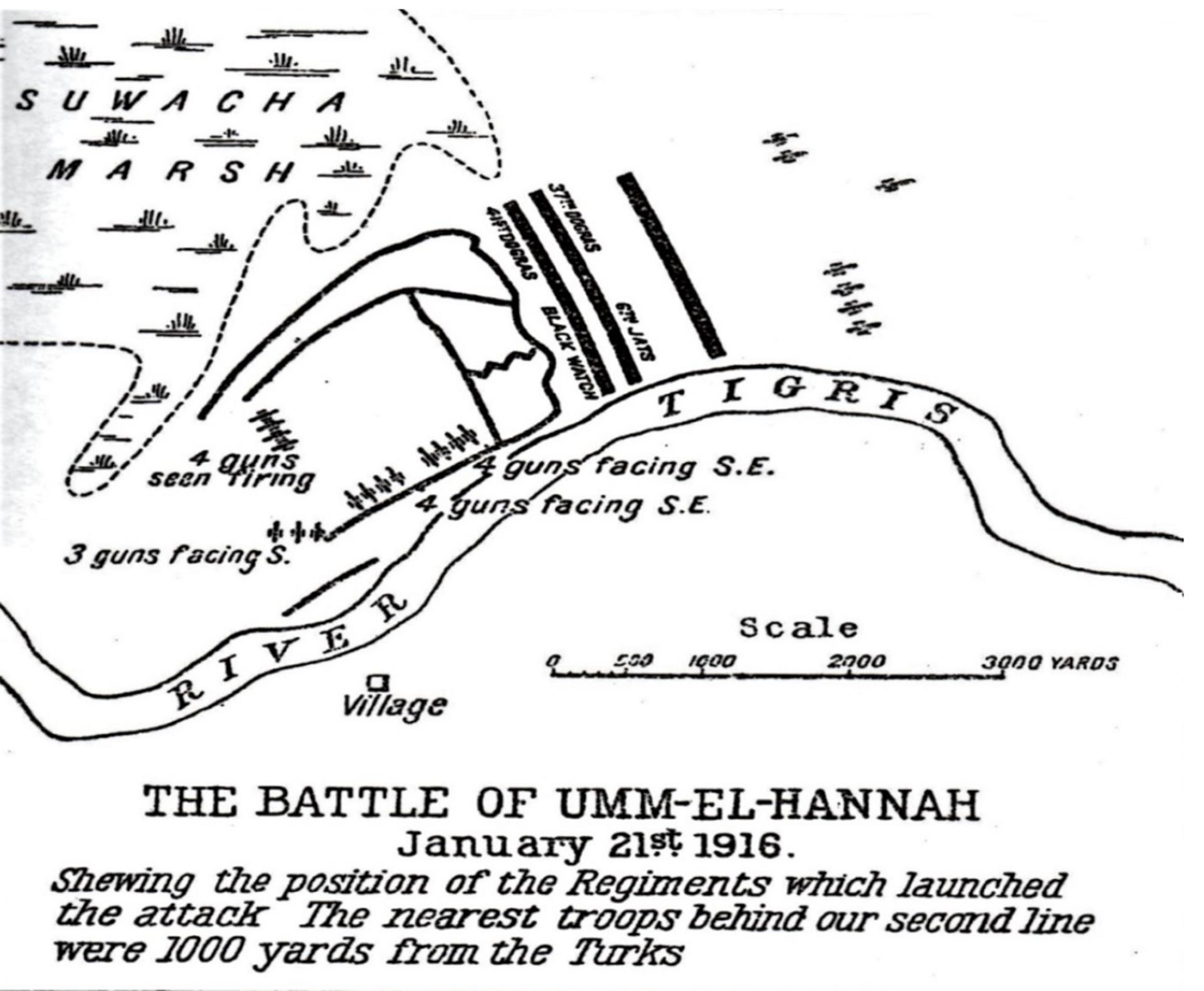

Conditions were atrocious, with thick mud making movement of troops and equipment extremely difficult. The enemy had had time to reinforce their defences and a combination of rising flood water and marshes on either side allowed no alternative but a frontal attack.

The British forward line was about 300 yards from the Turks, with 2nd Battalion The Black Watch at the left of the Line. 9th Brigade formed the Second Line, with the depleted 28th Brigade in Reserve. A number of 1/4th Hampshires were in the left of the second line, behind the Black Watch. The Turkish defensive position was a mile deep, fronted by 5 lines of interconnecting trenches each 200 yards behind the other.

The Turkish positions were bombarded, but the attack was in daylight, over flat ground, affording the British troops no cover, nor any element of surprise. Despite the difficulties, progress was made but heavy losses were sustained. 9th Brigade, including 4 men from the 1/4th Hampshire Regiment, attempted to reinforce a group of 60 who had managed to get within 150ft of the enemy trenches.

The Hampshires were particularly keen to do well, because part of their unit was incarcerated in Kut with 6th Division. Four of them had managed to make it through to the Black Watch.5

There were heavy casualties on the 21st January, the Hampshires being particularly hard hit. They started the battle with 16 officers and 339 other ranks, losing 13 and 275 respectively.

A small batch of the Hants were seen to advance at walking pace some 1,800 yards without taking cover. At 400 yards from the enemy one officer and two men were left. They walked coolly on and were within 300 yards of the Turkish trenches when the officer, the last of that forlornest of forlorn hopes, fell.

War Time Wanderings — 1/4th Battalion Hampshire Regiment (T.F.) 1914-1919 Harold V Wheeler (Based on Hampshire Regiment Journals) p15.

Unfortunately after just over an hour they were driven back by the Turks. Communications and visibility were poor throughout the attack and heavy rain turned the ground into thick, glutinous mud. Tired, cold and wet soldiers were told to withdraw to their positions of 2 days previously.

Under these appalling conditions the attack had to be abandoned, with severe losses, and a request made to the Turks for an armistice, so as to bury the dead and remove the wounded. With wounds undressed and unattended, many of the unfortunate wounded had to be left to crawl back as best they could through the mud, sometimes losing consciousness through loss of blood or the cold, and remaining in the mud and slime soaked to the skin for twenty four hours or more, before being picked up and carried to safety.

Mousley Captain E.O. The Secrets of a Kuttite p175.

The Turks were not removed from their defensive positions, the weather was worsening and flood waters were rising. This effectively marked the end of the first attempt to relieve Kut.

- Corporal Christopher Burt of the 1/4th Hampshires killed in action, 21st January 1916, commemorated on the Basra Memorial, Iraq

- Private Harold Rose of the 1/4th Hampshires killed in action 21st January 1916, commemorated on the Basra Memorial, Iraq

- Private Alfred Tarrant of the 1/4th Hampshires killed in action 21st January 1916, commemorated on the Basra Memorial, Iraq

- Private Ambrose Warne of the 1/4th Hampshires killed in action 21st January 1916, commemorated on the Basra Memorial, Iraq

(In the immediate aftermath of the battle, these deaths were reported as having occurred at Shaikh Saad, but the date links them firmly to the action at the Hanna defile.)

A further push against Hanna on 22nd February was indecisive. A second main attempt to relieve Kut was made at the end of the first week of March, with an attack on the Duijaila Redoubt on 8th March. The cost in personnel was high, for no reward. The failure enabled the Turkish Forces to strengthen their hold on Kut. News of the failure also affected the morale inside the besieged town. A third attempt began on 5th April with the eventual capture of the Hanna Defile and Fallahiya, but at high cost. Sannaiyat was attacked on 6th April, but despite heavy fighting a breakthrough was not achieved. Beit Aiessa (Bait Isa) was attacked on 17th and Sannaiyat again on 22nd. With food running out in Kut, an attempt was made by the steamer Julnar to run the blockade on the Tigris with supplies on the night of 24/25th April, but near Maqasis, about 10 miles by river from Kut, she was shelled by the Turks, killing the Captain, and then struck a cable that fouled her propeller. She was stopped, and had no choice but to surrender.

An attempt was made to buy the freedom of the Kut garrison, with Captain T.E. Lawrence in the negotiating team of three. That offer was rejected. There was nothing else to be done now to help their fellow soldiers. On 29th April 1916 Major-General Townshend surrendered. Of the 13,309 personnel who were surrendered, 2,869 were British (277 Officers) and 10,440 (204 Officers) were Indian (these last including 3,248 non-combatants (camp followers). At the time, it was one of the largest and most humiliating defeats in British military history. The Relief Force had suffered 23,000 casualties, including 10,000 in just 3 weeks of April during the final attempts.

The G. O. C. has sent the following letter to the Turkish Commander in Chief. –

Your Excellency,

Hunger forces me to lay down our arms and I am ready to surrender to you my brave soldiers who have done their duty as you have affirmed when you said your gallant troops will be our most sincere and precious guests.

Be generous then, they have done their duty, you have seen them in the battle of CTESIPHON, you have seen them during the retirement and you have seen them during the siege of KUT for the last five months, in which time I have played the strategic role of blocking your counter offensive and allowed time for our reinforcements to arrive in IRAQ.

You have seen how they have done their duty and I am certain that the military history of this war will affirm this in a decisive manner.

I send two of my officers Captain Morland and Major Gilchrist to arrange details.

I am ready to put KUT into your hands and go into your camp as soon as you can arrange details, [but I pray to you to expedite the arrival of food.]

I propose that your Chief Medical Officer should visit my hospitals with my P. M. O. He will be able to see for himself the state of many of my troops—there are some without arms and legs, some with scurvy. I do not suppose you wish to take these into captivity and in fact the better course would be to let the wounded and sick go to India.

The Chief of Imperial General Staff, London, wires me that the exchange of prisoners of war is permitted. An equal number of Turks in Egypt and India would be liberated for the same number of combatants.

Accept my highest regards.

(signed) General Townshend

Major General, Commanding 6th Division and the force in KUT

I would add to the above that there is [sic] strong grounds for hoping that the Turks will eventually agree to all being exchanged. I have received notification from the Turkish Commander in Chief to say I can start for CONSTANTINOPLE, having arrived there I shall petition to be allowed to go to LONDON on parole and see the Secretary of State for War and get you exchanged at once. In this [way] I hope to be of great assistance [to you] all.

I thank you from the bottom of my heart for your devotion to duty and your discipline and bravery and may we all meet soon in better times.

(signed) Charles Townshend

Major General, Commanding 6th Division and the force at KUT. KUT al AMARA 29th April 1916

Prisoners of War

Major-General Townshend

Unlike the regular troops, Major-General Townshend lived out the rest of the war in relative luxury. He was imprisoned, with a small retinue, on an island overlooking Constantinople. He was told to consider himself a guest of Turkey, and was even asked if he would like his wife and daughter to join him, the offer being vetoed by British High Command. Despite his comfortable existence he managed to spend his time in captivity feeling very sorry for himself and complaining by letter to everyone he could think of. We have to hope that he was unaware of the desperate plight of his men and after the war he did his best to absolve himself of any responsibility for their treatment.

The Officers

Many of the Officers had a tough time in captivity, particularly compared to their CO, but nowhere near as difficult as the men who served under them.

Having travelled together as far as Shumran, the Officers were then separated from their men and most travelled further on upriver by barge. Only one Officer was allowed to stay with each regiment.

The Officers were split into 4 groups and marched 370 miles to various locations. Unlike the Other Ranks they were allowed some mules and donkeys to transport their belongings. They marched for 10 days to reach Mosul on 25th May. Many of them had shared donkeys to ride, their food was better than the rations that were being given to the Other Ranks, and they were not treated with the same level of brutality. As the Officers were not travelling entirely on foot, most of them were ahead of the column of men and so only those left behind through sickness saw the conditions their men were forced to endure. Captain Mousley commented that they were

…always following the trail of dead, for every mile or so one saw mounds of our dead soldiers by the wayside.

Major Sandes (1920) quoted Crowley p181.

Most of the Officers and those lucky enough to be their orderlies, ended up at Afion Kara Hissar, Kastamuni, Changri, Kedos and Yozgad. The ordeals they had faced and were still to face were appalling, but in comparison to the Other Ranks, they were relatively lucky. The treatment they had to endure once they had reached their various destinations depended largely on the character of the Camp Commandant. They had access to a small amount of regular pay, which went back to the Turks to pay for their food, accommodation and rent of furniture. They could buy extra provisions from local traders, if not with actual money then with promisory notes which were honoured by the British Government after the war. The Officers in most cases had a remarkable level of freedom.

The prison conditions at Changri were less comfortable than elsewhere and this led to one of the more controversial incidents in the history of the prisoners. Colonel Annesley asked the Officers to pledge that they would not try to escape as he feared Turkish reprisals. This did not go down well with all of them. Officers are taught that it is their duty to try to escape when imprisoned by the enemy. This is partly so they may be able to rejoin the war effort, but equally as important, is the disruption it causes even if the escape attempt is unsuccessful. Those who agreed were rewarded by being moved to a more comfortable location. Escape attempts were however, made by some and a few were successful.

The Other Ranks

For the NCOs and men, British and Indian, the next two years were difficult beyond our imagining. Their first taste of life as a PoW was being marched up to Shumran. Although only 8 miles away it took the men 8 hours due to their poor physical condition. Although suffering from starvation they were denied food. Some managed to buy or barter some black loaves from their captors and were so desperate for food that many devoured these without first soaking the bread to make it edible. These biscuits of black bread were to form the basis of their diet.

Imagine an enormous slab of rock-like material, brown in colour, about five inches in diameter and three-quarters inch thick, made of the coarsest flour interspersed with bits of husk and a goodly portion of earth, and you have a tolerable idea of the diet on which the Turkish soldier seemed to thrive.

Elton (1938) quoted Crowley p185.

The average daily individual allowance was 2½ biscuits. When they arrived at Shumran they were each given 6 biscuits. That night several men died and it was put down to their weakened digestive state being incapable of dealing with the coarse food. Many men exchanged their belongings to get extra food, including their greatcoats which would be sorely missed later. Turkish soldiers sold food to the prisoners, including the rations that should rightfully have been theirs anyway. A British boat, under a white flag, managed to get some supplies through to the prisoners, but these supplies did not sustain them for long. Nearly 300 men died at Shumran in that first week of captivity.

Prisoners were frequently robbed of anything that may have been considered to be of value. Whereas the Officers were allowed to have some equipment with them the Other Ranks were denied that privilege, so they had no shelter from the sun or rain. The Turkish troops did not stop to bury anyone who died as the march progressed, although the troops themselves sometimes had the opportunity to do this. The Officers did try to ensure that their men were better looked after, the Turks agreed to transport the sickest men by river and they were promised that the men would have to march no more than 8 miles a day. This assurance lasted one day only. Had the Turks allowed more Officers to remain with their men they might have been able to influence the way the men were treated, but that is purely speculation. The Turks, who paid little attention to the way their own men were treated, certainly didn’t understand the preoccupation that the British Officers had with the men under their command.

With their Officers mostly travelling upstream by barge, the men began their long march. They had only what they could carry, without even a backpack for their belongings, which didn’t amount to much. For some it may have included basic washing supplies, a few spare items of clothing and, if they were lucky, a greatcoat or a blanket.

After five months of siege these men were as weak as rats from starvation, none of them fit to march five miles; they were full of dysentery, beri-beri, malaria and enteritis; they had no doctors, no medical stores, and no transport; the hot weather, just beginning, would have meant in those deserts much sickness and many deaths, even among troops who were fit, well cared for and well supplied.

RSM W Leach, A letter 19/06/1916, in the collection of the Royal Hampshire Regimental Museum.

During the march the men were under the control of mainly Arab guards, who were not averse to using harsh physical punishments. Men who couldn’t keep up were simply left to die, often stripped of their clothes and possessions. The Turks did not intervene, in fact they commented that the men were treated no worse than Turkish soldiers would be if they couldn’t keep pace with the column. Clean water was scarce, food was once more the black biscuits and the men were subjected to jeering and threats from Arab civilians who watched them pass. The harsh treatment from the guards is illustrated in a letter written by RSM Leach;

…it was reported to me that a man of the Hants Regt was lying helpless close to where the camels were unloaded… on being brought to me found him in an utterly exhausted condition. His belt had been stolen by the escort, and his shirt was very much torn. His body was one mass of scars and bruises which he accounted for by the brutal treatment he had suffered. He was flogged and kicked and hit with rifles… I made arrangements for Pte Woods to ride on the camels… he was left at the store depot with the other sick…

RSM Leach later learned of the soldier’s death and added,

‘I largely attribute his death to the harsh treatment he received.’6

Once they had reached Aziziya some of the men were transported to Baghdad by boat, but the vast majority continued to march. They were forced to cover 100 miles in 8 days. They were in a state of starvation, marching in daylight when the sun was at its hottest, herded and beaten by the Arab conscripts who were their escort, and all on a diet of 2 biscuits a day. On one occasion they were grateful for chappattis, green with mould, instead of the usual black biscuits. There was an allocation of one sheep per company and once they had some dates. Despite this, many made it to Baghdad.

The prisoners were marched to the railway station, where unlike their Officers they were not housed in buildings. Many by now had bartered, or lost through theft, all their possessions, including their shoes. After intervention from the Officers on their behalf, the men were moved to the shade. The American consul, Mr Brissell, some French nuns and Turkish and British medical officers did what they could to improve the conditions for the men. Some of the ill prisoners were returned to the British but there were still roughly 19 deaths a day among the captives.

The trek continued. The sick were left behind at Samara and thanks to the efforts of Major-General Melliss, some medical support was provided for them. The first group of Other Ranks reached Mosul on 3rd June, where there was some help to be found for the sick; 100 soldiers were allowed to remain there to receive treatment. Others owed their lives to the Germans they encountered en-route, who remonstrated with the Turks about the treatment of the prisoners, as well as arranging for medical help and better conditions in work camps. From Mosul the trek continued towards Ras al Ain, 200 miles west. They travelled via Dolabia, Rumailan, Kabir, Nisibin and Kochhisar. Many remained in these places to work on the Baghdad Railway. Many more men were to fall out and die on the trek westward. There are accounts of the horrors endured by the Other Ranks, including a hut full of sick men being left to die, and even a report of a sick man being buried alive. In 25 days the men were forced to march a distance of 370 miles. Sick men were left at Islahie with very little in the way of medical assistance. A German Warrant Officer tried to get help for them. After reaching Ras al Ain, many of the Indian soldiers, and some of the British, remained behind to work on the railway, which was under construction by the Germans. The rest continued on foot over the Taurus Mountains to Asia Minor. They were dispersed into many smaller working camps and in some cases met up with men who had been taken prisoner at Gallipolli. The British soldiers were mainly to be found in Ras al Ain, Afion Kara Hissar, Mamourie, Yarbaschi and Bagtsche working on railway construction projects. They had a further 2 years of captivity to endure.

The difference in rates of survival as a prisoner is seen clearly in the case of the 1/4th Hampshires. Of those captured at Kut, of 10 officers all survived, including one who escaped. Of the original 178 rank and file, only 50 survived. The conditions in the camps were very poor. Bagtsche camp was nicknamed The Cemetery and was closed down in 1917 when details of the conditions there leaked to the outside world. Yarbaschi was closed the same year for similar reasons.

The lot of an Other Rank prisoner of war is always liable to be a hard one. The lot of the unfortunate Other Ranks in the hands of the Turks was especially hard. There can be no excuse for the death of the large number of prisoners in the hands of the Turks. It was due to callousness and a complete failure to realise their responsibilities for their prisoners.

Afterword by Lieutenant-General Sir Graeme Lamb; Crowley p275/6.

There were a few NCOs who made a huge difference to the lives of the men. One of these was ex-WTC student RSM Billy Leach of the 1/4th Hants. Leach became the senior prisoner at Nisibin. He was extremely efficient and popular, playing a huge role in maintaining the morale of the PoWs in very trying circumstances. Like many others he died from typhus. His funeral was attended by a large number of prisoners as well as Germans. Conditions for the prisoners gradually improved after 1917. Care packages from home arrived. Mrs Bowker of Longparish near Andover, Hants, the widow of Lieutenant-Colonel Bowker who died commanding the 1/4th Hants at the Hanna Defile, established a Comforts Fund. She also kept a record of the prisoners, and arranged for each one to be adopted by someone who could provide the funds for the items to be sent. She chose to adopt Billy Leach. Her ledger lists the camp that each soldier was in, as far as was known. Some of the items she sent included: warm clothes and overcoats, playing cards, books, blankets, footballs and New Testaments.

A Xmas parcel was sent to each man consisting of: a plum pudding, 1lb bullseyes, a muffler, 50 cigarettes, 1/4lb tobacco, a pipe, soap, toilet paper, gloves, 3 handkerchiefs, a needle, cotton, a shirt socks and mittens in a bag, a type of powder or ointment and towels.7

Of the men taken prisoner at Kut, more than 3,000 were not heard of again. Most of these presumably were victims of the march into captivity. In one Baghdad graveyard alone, 1,248 of the dead were collected from camps and roadsides by the Graves Commission. In the circumstances, an accurate toll of the final human cost is difficult to arrive at, but of the 13,309 who surrendered at Kut, 13,078 went into captivity, the remaining 231 of the most sick being immediately exchanged and evacuated. Of the 13,078, at least 4,718 did not survive. This does not necessarily, however, include victims of other causes, including Spanish Flu which broke out in the prison camps in 1918. After the war, survivors erected a plaque in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral dedicated to the memory of all those of the garrison who died during the siege or afterwards in captivity. The number given is 5,746.

Prisoners of War From Kut

- Private Frederick Bolwell died of illness, 5th May 1916, commemorated at Basra, Iraq

- Private Charles Singleton died of illness, 1st August 1916, commemorated at Basra, Iraq

- Sergeant Andrew Bogie died of illness, 22nd September 1916, buried at Baghdad, Iraq

- Regimental Sergeant Major William Leach died of illness, 2nd May 1918, commemorated at Baghdad, Iraq

Prisoner of War from the Relief Force

- Private Henry Purkis died of illness, 1st September 1916, commemorated at Basra, Iraq

Other Members of the 1/4th Hampshires

- Lance-Corporal Arthur Woodfield died of illness, 8th June 1916, buried at Basra, Iraq

- Private Edward Hart died of illness, 11th July 1916, buried at Amara, Iraq

- Lance-Corporal Melville Woodrow died of illness, 27th July 1916, buried at Basra, Iraq

In December 1916 the Allied Tigris offensive resumed and by March of the following year Baghdad was finally occupied.

- Lance-Corporal Frederick Penney died of illness, 29th November 1917, buried at Baghdad, Iraq

Finally, one former college student not with the Hampshires but in the 1st Battalion Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, fought through the same campaign including the attempts to relieve the seige of Kut where some of his regimental fellows were incarcerated. Corporal Robert James Cambell Ferguson survived the Mesopotamian expedition and saw out the conflict with the Ottoman Empire which ended with the Armistice of Mudros on 30th October 1918 and the full Ottoman surrender two days later. He was then redeployed to Bombay (Mumbai) where he died of Spanish Flu on 7th January 1919.

Conclusions

The campaign in Mesopotamia was a disastrous one for the British. There are many reasons why so many men were lost for so little reward:

- The British consistently underestimated the strength and ability of the Turkish troops and command.

- The objectives, although originally sound, were expanded beyond what was reasonable for the level of logistical and medical support that was available, a typical example of Mission Creep.

- The challenges to be expected from both the terrain and the weather conditions were not sufficiently prepared for, nor were their implications for the mission understood.

- Many of the decisions made by high command were made without a thorough understanding of the factors involved, and with too little co-operation between India and Britain.

- Initial under-estimation of food supplies available at Kut caused an unnecessary sense of urgency for relief. This led to the Relief Force being sent out without sufficient preparation, troops or logistical support.

- The Arab population were misunderstood by the British, who had expected their complete support. This can perhaps be blamed partly on the arrogance of the Empire Mentality.

The campaign in Mesopotamia is:— a story littered with ambition, ego, ignorance, indifference, failure in communication, double talk and double crossing, a lesson in tactics, the operational art or lack of it and ultimately strategic drift.8

The treatment of the PoWs at the hands of the Turks has understandably received harsh criticism. There have been arguments in more recent times as to whether or not this is entirely fair. There are some factors underlying their behaviour that might be considered. At the end of the siege the Turks had a large population of prisoners on their hands. To stay at Kut with them would risk attacks from the Relief Force. They needed to move the prisoners away from the area quickly. They had a huge area of inhospitable ground to cover with their captives before they arrived at their desired location and only the basic food typically issued to the Turkish soldier. The Turkish Army did not have the same attitude of care towards their rank and file soldiers as the British. The ordinary Turkish soldier was treated very harshly so it is not surprising that their prisoners should receive the same or worse treatment. Even accepting that the requirements of The Hague and Geneva Conventions held little sway in that part of the world at the time, we have to consider if these factors excuse the way the prisoners were treated. Was it reasonable to force men who were on the verge of starvation to march for such long distances, over such harsh terrain, in extremes of heat, without proper medical care and without sufficient food and drink? Was it necessary to mete out such cruel punishment to men who were at the limit of their physical capabilities? At the end of the siege the remaining soldiers were in a frightful physical condition, fit for nothing,

…let alone for the awful sufferings they were to undergo in captivity, for which Turkish incompetence and carelessness as well as sheer brutality and cruelty were responsible.

It is difficult, then or now, to justify the way the prisoners were treated. Much of the harshest treatment on the march was at the hands of Arab guards in the service of the Turks, but ultimately control of those guards was the responsibility of Turkish commanders. The well-being of PoWs is the responsibility of those who hold them in captivity and they should be answerable for their actions. Sadly, after the War, the changing priorities of geopolitics meant that the prisoners’ sufferings were never compensated, as a new regime in Turkey was diverted from the potential influence of newly-Soviet Russia.

Researcher and Author: Dee Sayers

List of Maps and Illustrations

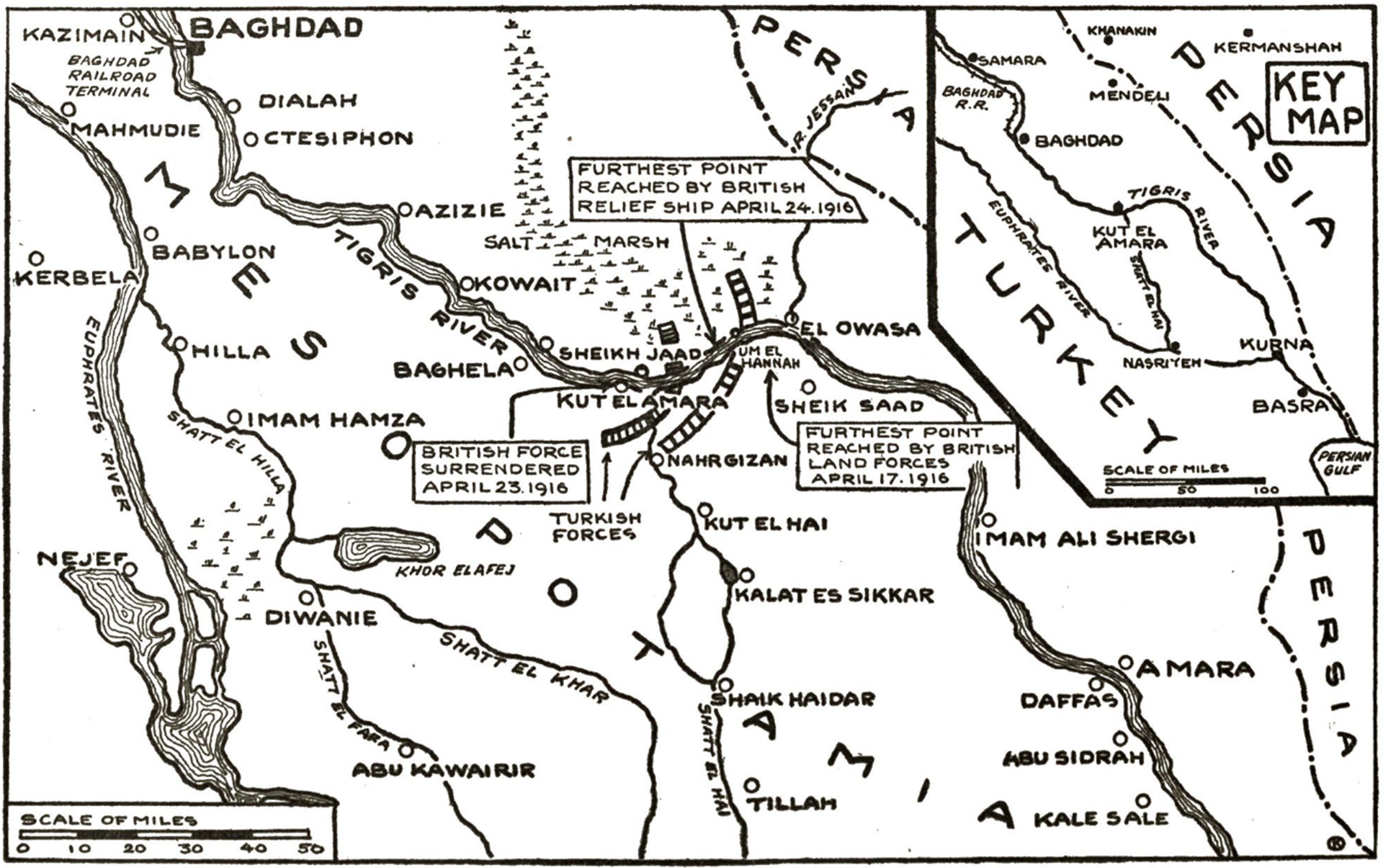

- Fig 1. Map of the Campaign in Mesopotamia. Churchill, Miller and Reynolds, The Story of the Great War, volume v. New York: P F Collier & Son. Specified year 1916, actual year more likely 1917 or 1918. Available at http://www.gutenberg.org/

files/29341/29341-h/29341-h.htm [Accessed 13 June 2018] - Fig 2. A View of Kut-al-Amara in 1916. Le Miroir N°171, page_14_vue_de_Kut_el_Amara en 1916. Author Garitan 1916, 2012 pour les modification set le téléversement

- Fig 3. Sketch Map of the Kut Position and Defences. http://www.lightbobs.com/1915-

december-siege-at-kut-el-amara.html - Fig 4. Turkish Troops in Position Besieging Kut. Turkish General Staff “ in the public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/

wiki/File:Mesopotamian_campaign_

6th_Army_Siege_of_Kut.png - Fig 5. Indian Soldiers at the Fall of Kut. UK Government Photo in the public domain; walesatwar.org via https://commons.wikimedia.org/

wiki/File:Indian_army_soldiers_after_

siege_of_Kut_Al_Amara_on_the_

Tigris _River_1916.jpg - Fig 6. Illustration showing the relief effort. https://no.m.wikipedia.org/

wiki/Fil:Kut-el-Amara-map.jpg - Fig 7. Greater Detail of the 7th Division Initial Positions at the Hanna Defile. From Candler, E. (1919). The Long Road to Baghdad. London: Cassell & Co Ltd, London. Reproduced in Crowley, p83.

- Fig 8. Winchester Alumni in Mesopotamia. Origin unknown, Hampshire Record Office 47M91W/S5/5/10.

- Fig 9. The Relief Force Bridging the River Tigris. From The War Illustrated, 12th February 1916, Page 620.

- Fig 10. General Townshend’s Communique to his Troops Containing the Text of his Letter of Surrender. From The William Leach Collection. Records of RSM W.F. Leach including the records of Mrs. E. Bowker [documents, notebooks, photographs and artefacts] The Royal Hampshire Regimental Museum, C2: Leach Box, M/684 Leach, Winchester.

- Fig 11. Newspaper cartoon, unattributed but possibly from The Continental Times, described as a propaganda newspaper published for English speaking prisoners of war, or a pro-German newspaper for Americans in Europe, published in Berlin.

Bibliography

Atkinson, C.T. (1952). Regimental History—The Royal Hampshire Regiment. Volume 2 1914-1918. Glasgow: Robert Maclehose & Co. Ltd. The University Press.

Crowley, P. (2016). Kut 1916: the forgotten British disaster in Iraq. Stroud: The History Press.

The Hampshire Chronicle (1976). Hampshire Chronicle, 30th April 1976. [newspaper article] The Royal Hampshire Regimental Museum, 71M88W/3/3, Winchester.

Mousley, Capt. E.O., RFA (1922). The Secrets of a Kuttite. An Authentic Story of Kut, Adventures in Captivity and Stamboul Intrigue. London & New York: John Lane, The Bodley Head Ltd (London) and John Lane Co (New York).

The Siege of Kut-al-Amara. Hampshire Chronicle, 30th April 1976. Hampshire Record Office archive 71M88W/3/3.

Wheeler, H.V. (unknown). War Time Wanderings—1/4th Battalion Hampshire Regiment (T.F.) 1914-1919. Winchester: Published privately. Avaiable in the collections of The Royal Hampshire Regiment Museum and the Hampshire Record Office.

- Statistics from Wilson (1930) p 60 quoted Crowley p26 “Kut 1916“ The Forgotten British Disaster in Iraq by Patrick Crowley, The History Press, 2016 (first published 2009), ISBN 978 0 7509 6606 1.

- Statistics from Wilson (1930) p 60 quoted Crowley p26, Kut 1916—The Forgotten British Disaster in Iraq by Patrick Crowley, The History Press, 2016 (first published 2009), ISBN 978 0 7509 6606 1.

- A greyback was an army issue collarless shirt

- The Hampshire Chronicle, 30th April 1976. The Siege of Kut-al-Amara.

- Candler, Edmund The Long Road to Baghdad (Two volumes), Cassell & Co Ltd, London (1919) quoted by Crowley p84.

- Mrs Bowker’s Fund Ledger, from the collection of The Royal Hampshire Regimental Museum.

- Anonymous (1934) The War Records of the 24th Punjabis, quoted Crowley p231.

- Afterword by Lieutenant-General Sir Graeme Lamb; Crowley p275/6.