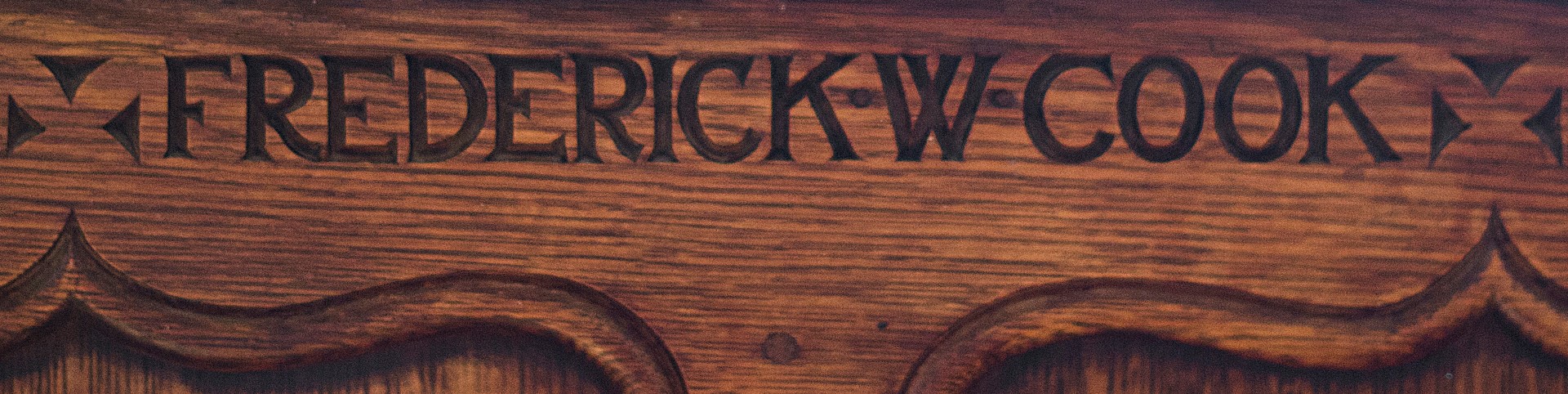

Frederick Willie Cook

8th September 1892 – 29th December 1917

Lance Corporal,1 3rd Bedfordshire Yeomanry (attached to 1/1st Lincolnshire Yeomanry), Regimental Number 30625, died of illness on the 29th December, 1917, at Port Said, Egypt and is buried at the Port Said War Memorial Cemetery.

Family and Background

With the exception of his mother, Margaret Gill, Frederick’s family were Gloucestershire people. She was born in Stratford-on-Avon, Warwickshire but is recorded as having found a position as a domestic servant in a family home in Cheltenham, aged 18, in 1871.

Head of the Cook family was Charles. He was born in 1856 to Walter, a blacksmith’s labourer, and Emma—both of Cheltenham—and by the age of 15 had become a pupil-teacher, teaching in a Cheltenham School. After training in the mid-1870s, he secured an appointment as schoolmaster at Longney, in Gloucestershire.

On 27th August, 1877, Charles married Margaret in St. Mary’s church, Cheltenham. By this time, Charles evidently had established himself in Longney and had close associations with the church. On the marriage certificate we see the signature of neither the incumbent of St. Mary’s, nor his curate, but that of the Rev. Nussey, Vicar of Longney.2

Longney is still a very small village today, standing in rural isolation on the east bank of the tidal Severn. In 1891 the population was only 344 persons, falling to 313 in 1904. 3 4 The school was a National School for boys and girls. Built in 1865, it was later enlarged under Charles’ tenure in 1896 to accommodate 89 children. In 1897 the average attendance was 71. The school stands directly across the lane from the ancient parish church of St Laurence and the schoolmaster was provided with a house nearby. 5 6

The schoolhouse was to become home for the children who were to be born to Charles and Margaret, all of whom were born in Longney. Listing them in order of birth, with their eventual occupations, location and source census date, they were:

- Margaret Emiline b.1878. Elementary school teacher in Gloucester (1911)

- Charles Percival b. 1880. Electrical engineering Foreman, Handsworth, Birmingham (1911)71973

- Harold Walter b.1883. Motor mechanic foreman, Datchet, Bucks (1911) 8 1949

- Cecil Francis b.1885. Coach Builder, Tredworth, Glos. (1901)

- Reginald Arthur b.1887. Motor fitter, Datchet, Bucks (1911) d.1968 9

- Amy Eleanor b.1889. Certificated teacher, Fishponds, Bristol (1911) 10

- Frederick Willie1892. Student teacher, Westbury-on-Severn (1911) d.1917

- Eva Mary b.1892. No occupation listed (1911)

- Wilfred Edward b. and d. 1894

What is remarkable is the presence of four teachers in the family: father and three children. Additionally, in 1901 Margaret Senior is listed as being employed as ‘Teacher of sewing in school’. Since all of the children would probably have begun as pupil-teachers,11 and bearing in mind the geographical isolation of Longney, the village school must have seen a succession of pupil-teacher Cooks from 1893 (the probable first year of Margaret Junior’s apprenticeship) into the 20th Century, when they moved away.

Charles and family moved to Westbury on Severn. Although just over three miles away as the crow flies, the two villages are separated by the broad tidal estuary of the River Severn; a sixteen-mile road journey is required to travel between the two. Charles continued in a headship role at his new school: Westbury-on-Avon National School (National Schools were Church of England foundation). In 1914 this had an average of 40 boys, 30 girls and 20 infants attending each day. There was also a Council school of the same size in the village but we know from his later College Student Record that Frederick attended Westbury National School. The move to the village must therefore have been made well before September 1904 when he began Lydney Secondary School. Thus Frederick’s schooling under the watchful eye of his father came to an end—perhaps with relief as it would have been an unenviable position for any schoolboy.

We know little of his schooling in Lydney. In July 1910 he sat and passed the Cambridge Seniors’ examination (more formally known as Cambridge Senior Local Examinations). This enable him to apply for a place at training college. This he did, and in the intervening year he took a position as a Student Teacher at his father’s school.12 Frederick had also sat and passed examinations in the following elective subjects: Plant Ecology and Flower Classification, Matriculation in Botany, and Physical Training. There is full article on the school system and the organisation of teacher training here.

By 1911, only Frederick Willie and his twin sister Eva Mary were still living at home with their parents. In the Autumn, Frederick had packed his bags and headed off to study and train—a necessary step towards being a Certificated teacher.

Winchester Training College

Frederick’s two years as a student at Winchester would have been very different from university life experienced there today. We turn to former Principal Martial Rose’s history of the college13 for an insight:

The weekly routine at the turn of the century was less severe than in the earliest days of the college. On weekdays reveille was sounded by the bell monitor at 6.15 a.m., making his way through the dormitories, ringing a hand-bell. A cup of cocoa stood ready for students at 6.30 in the dining hall, and roll-call, taken at 6.45, was followed by an hour’s lecture. Then came morning service and afterwards breakfast at 8.30 a.m. On Mondays, Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays lectures lasted from 9 a.m. until 12.50 p.m., with a break from 10.45-11 00 a.m. Lunch was at 1 p.m., and at 2 p.m. on the above days there followed a 1½-hour art lesson or psychology or hygiene or criticism lesson. This still left time for football, cricket, or tennis on the dytche14 before tea at 5 p.m. From 7-9 p.m., commencing with roll-call, all students undertook private study in their appropriate lecture room, either junior or senior. A member of staff supervised in one room and a prefect in the other. Evening chapel was at 9.15 p.m., followed by supper at 9.30”then to bed, with lights out at 10.30 p.m. On Wednesdays and Saturdays the time-table was varied to allow for set matches being played.

There are snippets of the less formal side of college life recorded in the student publication, The Wintonian. It is here we find the only direct reference to Frederick. In the Dormitory Cup, an annual football competition where everyone competed in fancy dress, he was reported as dressing up as Apollyon. 15 A full match commentary would have been entertaining.

On leaving college he moved east once more, this time to Canterbury, where he had secured a position as an assistant teacher at the City Council Boys School.16 Here, Frederick would have completed his two statutory years as an assistant teacher to achieve certification had the war not intervened.

Military

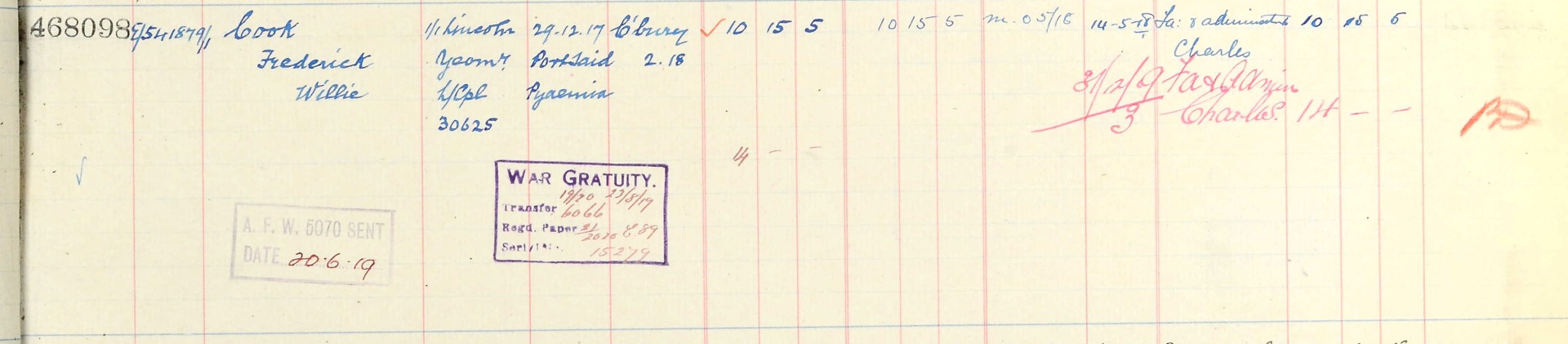

Frederick enlisted in the Bedfordshire Yeomanry. We do not know why, when or where as his records, like those of so many of WWI personnel, were destroyed in an air raid in WWII. What follows is therefore mostly conjecture from circumstantial information found in indirect sources. However, we begin on the solid ground of one important piece of evidence did survive: his entry in the Register of Soldiers’ Effects.

First we need to acknowledge a problem. This record shows him clearly as a Lance Corporal. The only other documentation we have (Commonwealth War Graves documents concerning his burial, and his Medal Roll entry17) list him as a Private. It is possible that he had received a promotion just before his death.

It is helpful to know that his War Gratuity is £14 0s 0d. This amount is commensurate with 36 months of service, or joining up in the month from 30th January, 1915.18 His Regimental Number (30625) also helps to date his Attestation more accurately: numbers 30629 and 30631 were issued on 1st and 2nd February, 1915 respectively. It is therefore probable that he joined the Bedfordshire Yeomanry on the 31st January or 1st February, 1915 and it would be with them that he received his basic training.

Within a few months, he was transferred to the 1/1st Lincolnshire Yeomanry, based in Norfolk. On 27th October, 1915 they embarked at Southampton for Salonika on SS Mercian (image above, SS Mercian. Arthur James Wetherall Burgess (1879–1957) © Artist’s estate / Museum of Lincolnshire Life). En route, the destination was altered to Alexandria, Egypt. The voyage itself was a rude awakening and the Battalion saw its first casualties even before setting foot in a theatre of war. The story is as follows:

‘…they embarked in the SS Mercian for Salonica as infantry. All went well until nine hours from Gibraltar, when she was attacked by submarine… The Mercian had no guns and some of the troops, under Major JW Wintringham, MC, brought up their machine guns, but were outranged. Still the men made a fight for it. The captain handled his vessel with skill. Private Thompson, a Lincolnshire man, taking the wheel under his direction, and men of the Yeomanry going down in the stokehold and keeping up steam after the crew had left the vessel. The vessel was hit several times, and the casualties numbered about a hundred, Capt Lord Kesteven being among the killed, but the Mercian eventually got clear and made for Oran, in Algeria, where the French treated them very kindly. Lord Kesteven and about 30 NCOs and men who were killed were buried at sea or at Oran, and five days later the troops again set sail, calling at Malta, and then proceeding to Alexandria.’19

Frederick and his regiment were to take part in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign, fought against German-led Ottoman-Empire troops. This had begun as a defensive action to stop an attempt to take control of the vital Suez Canal.

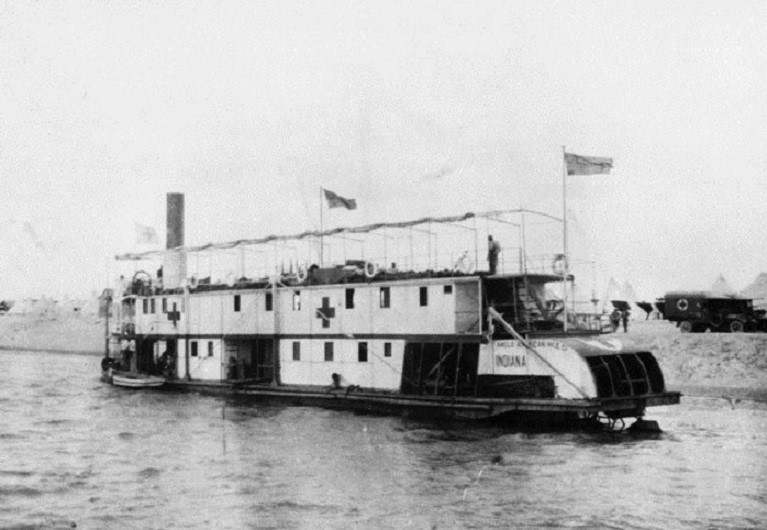

Above and below: Hospital trains and boats were used for troop evacuation to Port Said via Kantara. The train carriages were painted white and windows shuttered to keep the interior as cool as possible.20

Throughout 1916, the troops were engaged in driving the Turkish forces out of the Sinai Peninsula. By April 1917 Sinai had been secured and allied forces had pushed up into Southern Palestine, around the Gaza area. Following a stand-off at Gaza from April to October 1917, the ANZAC-led21 advance recommenced, leading to the Battle of Jerusalem in November and December.22

Quite what part Frederick was to play in these events remains unknown. It would have been tiring, hot and dusty work. For most of the time that the Lincolnshire Yeomanry were in the Middle East they would be part of the 22nd Mounted Brigade and, in February 1917, come under orders of the ANZAC Mounted Division.

Returning to what we do know, we see that Frederick died at the end of December, in Port Said, at the mouth of the Suez Canal. Port Said had become the main medical evacuation centre for the region.23 When Frederick became ill—whether from an infected wound or more general illness we do not know—he would have been evacuated 140 miles by train on the newly-built Palestine to Kantara 24 railway line,25 and then taken the final 30 miles by hospital boat up the Suez Canal to Port Said, where the ANZAC-run hospitals were on the quays.

At the time, before antibiotic treatment, pyaemia—his stated cause of death—was almost universally fatal. It was a form of septicaemia caused by staphylococcus bacteria resulting in abscesses in various parts of the body, including internal organs, and often resulted in septic pneumonia. The medical care in this campaign was excellent and Frederick would have received good care by the Commonwealth medics. He died on 29th December, 1917.

His body was interred Port Said War Memorial Cemetery where there are 544 Commonwealth burials from the First World War, mostly of those who died in the hospitals. It is situated on the western outskirts of the town on the strip of land between the Mediterranean Sea and Lake Manzala.

Researcher and Author: John Vickers

Footnotes

[1] Possibly Private—see below

[2] Rev. Edward Richard Nussey B.A. (Oriel College, Oxford) was appointed by The Lord Chancellor to the living of Longney since 1865 after a Curacy at Oundle. He resigned in February 1904

[3] In 1851 the population had been at an all-time high of 504. The fall was attributed to demolition of houses. By 1891 the population decline had slowed. Source: British History Online

[4] Cheltenham Chronicle, Saturday 6th February 1904

[5] Kelly’s Directory of Gloucestershire for 1897, p.230

[6] The school is now Longney Church of England Primary School.

[7] Married Glendoura Adelaide Brettell (1887-1958) of Smethwick, Birmingham, on Boxing Day, 1910.

[8] Married Perleyhett McCrow (1889- ) of Chelsea, on July 30th, 1910

[9] With both Harold and Reginald working in the same trade in the same place, it is likely that they worked together. There is no garage listed at that time in Datchet (Kelly’s Directory, 1911) but numerous boating businesses. They may have been marine motor mechanics.

[10] Married Benjamin Arthur Greenfield (1890- ) of Swindon and 16th Battalion Royal Warwick Regiment on 13th November, 1915

[11] By this time the system of pupil-teachers was being brought to an end, favouring secondary education as a prerequisite to teacher training, but it still was in use, especially in rural areas

[12] His College Record at this point does not make sense. It records that after secondary school he became a pupil teacher and then an assistant teacher (both at his father’s school). This is highly unlikely. His father, who filled in the 1911 Census form and who would have known exactly what his status was, records him as a Student Teacher (i.e. working his allowed 1 academic year between entry exam and college). This fits exactly with his pattern of education.

[13] A History of King Alfred’s College, Winchester 1840-1980 by Martial Rose

[14] The dytche was the only level area of the college campus and was used as a sports field. The early hand-coloured photograph above is taken from the dytche.

[15] The apocalyptic angel of death or destruction, found in Job (in the Hebrew form of the name: Abaddon) and Revelation. Also similarly a demon in Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, lord of the City of Destruction.

[16] This is the name of the school as listed in College records. It has not been possible to match this name with any known school.

[17] These may not be independent of each other, so should not be seen as corroborating or validating each other

[18] Fortunately, for the purposes of this calculation, the War Gratuity for a Private and Lance Corporal are the same

[19] Grimsby Telegraph First World War Centenary Commemorative Supplement Published Jul 29, 2014

[20] AWM Images reproduced strictly for non-commercial research and private study purposes as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, as amended and revised.

[21] ANZAC: Australian and New Zealand Army Corps

[22] The push continued to the North after this: Damascus and Aleppo were captured, before the Ottoman Empire agreed to the Armistice at Mudros on 30 October 1918

[23] From May 1915 it began to receive wounded and sick soldiers from the Gallipoli conflict. By 1917 there were five hospitals at the port

[24] Modern-day El Qantara

[25] Begun in January 1916, it runs along the Mediterranean coast. Eventually it would be built further up the coast to Haifa

Sources

Ancestry (2018). Home page. [online] Available at: www.ancestry.co.uk [Accessed 2018]

Australian War Memorial (2018). Home page. [online] Available at https://www.awm.gov.au/ [Accessed 2018]

British History Online. (1972). Longney. [online] Available at http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol10/pp197-200 [Accessed 2018]

British Newspaper Archive (2018). Cheltenham Chronicle, Saturday 6th February 1904. [online] Available at: www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk [Accessed 2018]

Commonwealth War Graves Commission, (2018). Home page. [online] Available at www.cwgc.org/ [Accessed 2018]

Kelly’s Directory (1897 and 1914). Kelly’s Directory of Gloucester, 1897 and 1914. [online] Available at: http://specialcollections.le.ac.uk/cdm/ref/collection/p16445coll4/id/8888 [Accessed 2018]

The Long Long Trail, (2018). Lincolnshire Yeomanry. [online] Available at: http://www.longlongtrail.co.uk/army/regiments-and-corps/the-british-yeomanry-regiments-of-1914-1918/lincolnshire-yeomanry/ [Accessed 2018]

Rose, M. (1981). A history of King Alfred’s College, Winchester 1840-1980. London: Phillimore

Vickers, J. The University of Winchester Chapel Memorial Rail image

| University of Winchester Archive “ Hampshire Record Office | ||

| Reference code | Record | |

| 47M91W/ | P2/4 | The Wintonian 1899-1900 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/5 | The Wintonian 1901-1902 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/6 | The Wintonian 1903-1904 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/7 | The Wintonian 1904-1906 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/8 | The Wintonian 1905-1907 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/10 | The Wintonian 1908-1910 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/11 | The Wintonian 1910-1914 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/12 | The Wintonian 1920-1925 |

| 47M91W/ | D1/2 | The Student Register |

| 47M91W/ | S5//5/10 | Photograph of 5 alumni in Mesopotamia |

| 47M91W/ | Q3/6 | A Khaki Diary |

| 47M91W/ | B1/2 | Reports of Training College 1913-1914 |

| 47M91W/ | Q1/5 | Report and Balance Sheets 1904- 1949 |

| 47M91W/ | R2/5 | History of the Volunteers Company 1910 |

| 47M91W/ | L1/2 | College Rules 1920 |

| Hampshire Record Office archive | ||

| 71M88W/6 | List of Prisoners at Kut | |

| 55M81W/PJ1 | Managers’ Minute Book 1876-1903 | |

| All material referenced as 47M91W/ is the copyright of The University of Winchester. Permission to reproduce photographs and other material for this narrative has been agreed by the University and Hampshire Record Office. | ||