Frederick William Randolph

*In many of his records, including his hospital admission at death, he is listed as ‘Private’. His headstone, his entry in Soldiers Died in the Great War, 1914-1919 (HMSO) and the newspaper article (below) record his rank as Lance Corporal. A promotion (probably to an ‘Acting’ or ‘Temporary’ rank, which didn’t carry an increased pay grade) shortly before his death is assumed.

Serendipity

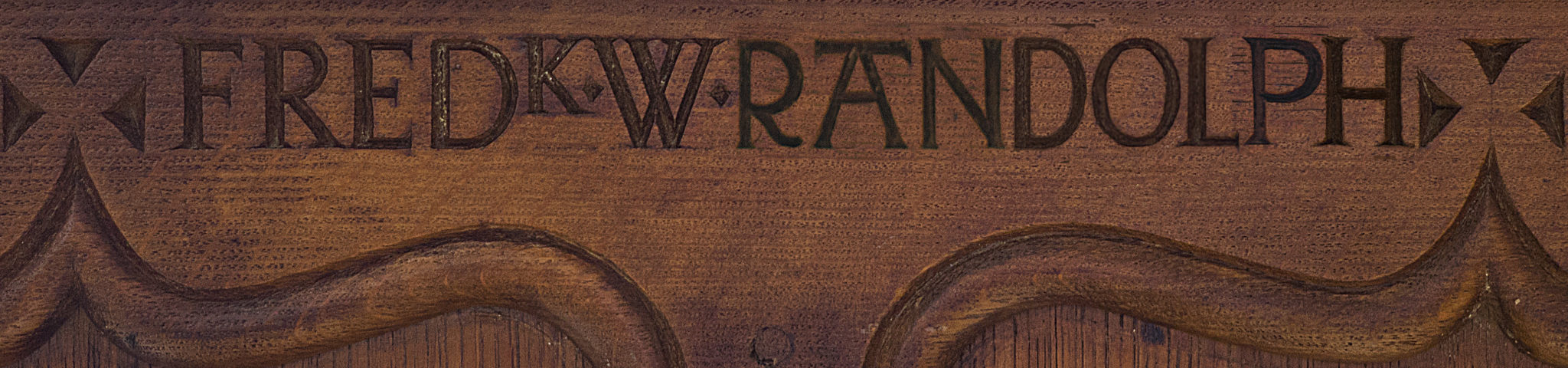

The Winchester Training College Fallen project, from its inception, focused on recording the life stories of the sixty men who were named on the Memorial Rail in the college chapel. When these stories had been written and the work almost complete, a chance discovery unearthed a possible sixty-first former student, who may have been missed in 1922 when the names were carved in the ‘oak panelling placed round the walls as a memorial to the students who fell in the Great War.’(Rose, p.69)

The college chapel: the oak panelling, which carries the carved names of the fallen on its top frieze, is visible on the left-hand lower wall.

Tracing the life stories of the sixty involved extensive exploration of many archives and collections. These searches tended to be based on the name of the student being researched, or his family members, places of residence or teaching, or other specific subjects related to the unfolding narrative. As a ‘mopping-up’ operation, at the end of the project, it was decided that a more general search of the British Newspaper Archive was needed, based on a search for all college activity. This was undertaken in the hope of picking up oblique references to any of our men, or articles where the student’s name is present but had been missed in previous searches due to poor Optical Character Recognition (OCR) in the digital archiving process. The latter is a particular problem with newspaper archives as the quality of newsprint is often low. Such a search had been considered in the early phase of the project, but its extent was somewhat daunting: searching for “Winchester Training College” for the period covered by the sixty, returned around five hundred articles. The search was therefore deferred until the bulk of the work was done and time became available.

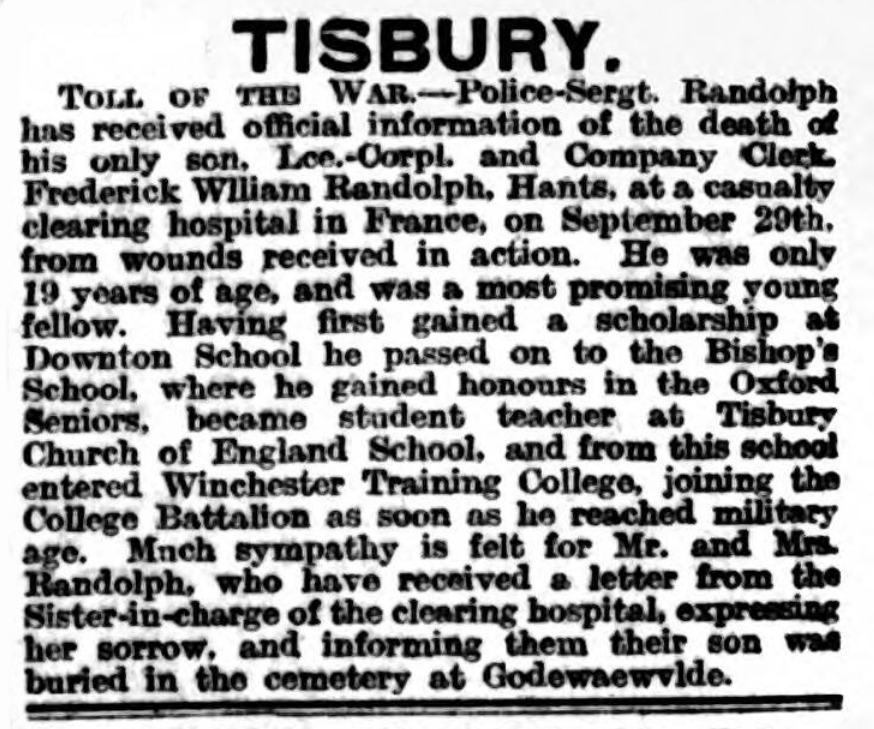

The results were useful: 38 articles were found that augmented or verified the stories of the sixty. There was one article, however, that stood out. It was carried in the Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser of Saturday, 27 October 1917, page 12:

This, then, is the story of Frederick William Randolph—perhaps our sixty-first man of the Winchester Training College Fallen.

The Wiltshire Randolphs

Frederick’s forebears were Wiltshire people through and through. His great-grandparents (7 of the 8 have been traced ) were born in the late 1700s or early 1800s in the small villages just to the east of Trowbridge: Steeple Ashton, West Ashton, Keevil, and Great Hinton. All the men were recorded as Agricultural Labourers or Agricultural Servants. ‘The usual distinction between a farm servant and a farm labourer was that a servant was an adolescent boy or an unmarried man who was hired for a year and who lived on the farm, whereas an agricultural labourer was usually a married man who lived elsewhere (often in a tied cottage) and who was paid a daily or weekly wage for the job that he performed.’ (Hey). This distinction, while generally found in these Wiltshire records, is not strictly maintained: his father Fed Randolph is ‘Labourer’ (1881) but ‘Servant’ (1891).

Both locality and occupation were perpetuated down the generations: grandfathers James Randolph (b.1842, West Ashton) and Thomas Sturges Pearce (b.1834, Keevil) were both Farm Labourers. His grandmothers were also from rural labourer’s families in the same area: Esther Randolph (née Newman, b.1844, Steeple Ashton) and Priscilla Pearce (née Overton, b.1847, Atworth). Esther’s background was from the same social stratum: her father was described as a gamekeeper just before his early death, in the 1841 Census, and Priscilla’s father was an agricultural labourer.

The trend both continued and ended with his father, Fred Randolph (b.1868, West Ashton). At the age of 22 (April 1891) he was working as an agricultural servant but within 18 months, his occupation had changed and was recorded as a Police Constable. (Marriage Register entry, November 12th 1892.) His age in the register is incorrectly stated as 26. There is an inconsistency in the record of his age throughout the census and other records. His date of birth recorded on the 1939 England and Wales Register is definitive (22 August 1868) as the Register was the basis for WWII identity cards and had legal force. Ages in the narrative are calculated from this date.

Steeple Ashton. Date and copyright unknown.

At the age of 24 he married 21-year-old Louisa Jane Pearce on 12th November 1892 in the Parish Church of St Mary the Virgin, Steeple Ashton. A little over one year later Dulcie Viola was born (9th December 1893), followed by Dorothy Louisa on 27th August 1896, Frederick William on 29th December 1897 and Gwendoline Felicia on 6th November 1907. Both Fred and Louisa were from large families; the children would have at least 28 aunts and uncles: Fred had 6 sisters and 2 brothers; Louisa had 4 sisters and 4 brothers. There is a possibility that some of their marriages have not been traced.

Shortly before their marriage, Fred had moved out of the family home and had become a Police Constable in the ancient Saxon town of Malmesbury, Wiltshire. It was here that he and Louisa were to make their home, one of three families living in tied Police houses which formed part of the town’s Police Station in Gastons Lane, in an area known then as Westport St. Mary, 500 yards from the town centre. He worked under Superintendent Alfred Webb, 20 years his senior, and Sergeant Alexander Mackie, a Scot and 3 years his senior.

Dulcie, Dorothy and Frederick were born in Malmesbury. Gwendoline was born in Longbridge Deverill, Wiltshire, 30 miles to the south. Fred had been posted to this Wiltshire hamlet sometime between April 1901 and May 1902. These date limits are defined by two sources: the 1901 Census, and Fred’s acting as a police witness in a trial in Trowbridge Police Court in May 1902 (Warminster & Westbury journal, and Wilts County Advertiser, Saturday 10 May 1902, p.8) It is here that we read a typical appearance of Fred in print:

PETTY SESSIONS, Thursday Before the Marquis of Bath (chairman), Mr. W.F. Morgan, and Col. Alexander

BAD LANGUAGE—Walter Whatley, labourer, of Longbridge Deverill, and John Carpenter, labourer, of Cockerton, were charged with using bad language at Longbridge Deverill on August 28th.—P.C. Randolph stated the facts and defendants were each fined 2s. 6d.

Other news items carry his witness statements in trials concerning: the theft of a broom head, driving a cart at night without lights, threats from a farmer, a publican allowing drunkenness on his premises, sleeping under a hayrick with no visible means of subsistence, and drunkenness. Such was the lot of a village bobby in a sleepy hamlet—although we need to note that his work included some duties in the town of Warminster, which had a population of 17,490 in 1901 (Census).

The older girls were showing an aptitude for handwork. In the nearby Warminster Cottagers’ Garden Society 49th Annual Show, Dulcie and Dorothy both won 2nd prize in Knitting and Crochet work, Dorothy a 2nd in Patchwork and a 1st in Plain Work. It was also recorded that the exhibition marquee collapsed during the show due to high winds. (Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, Saturday 20 August 1904, p.5)

A village policeman, 1912. Copyright Elsworth Chronicle

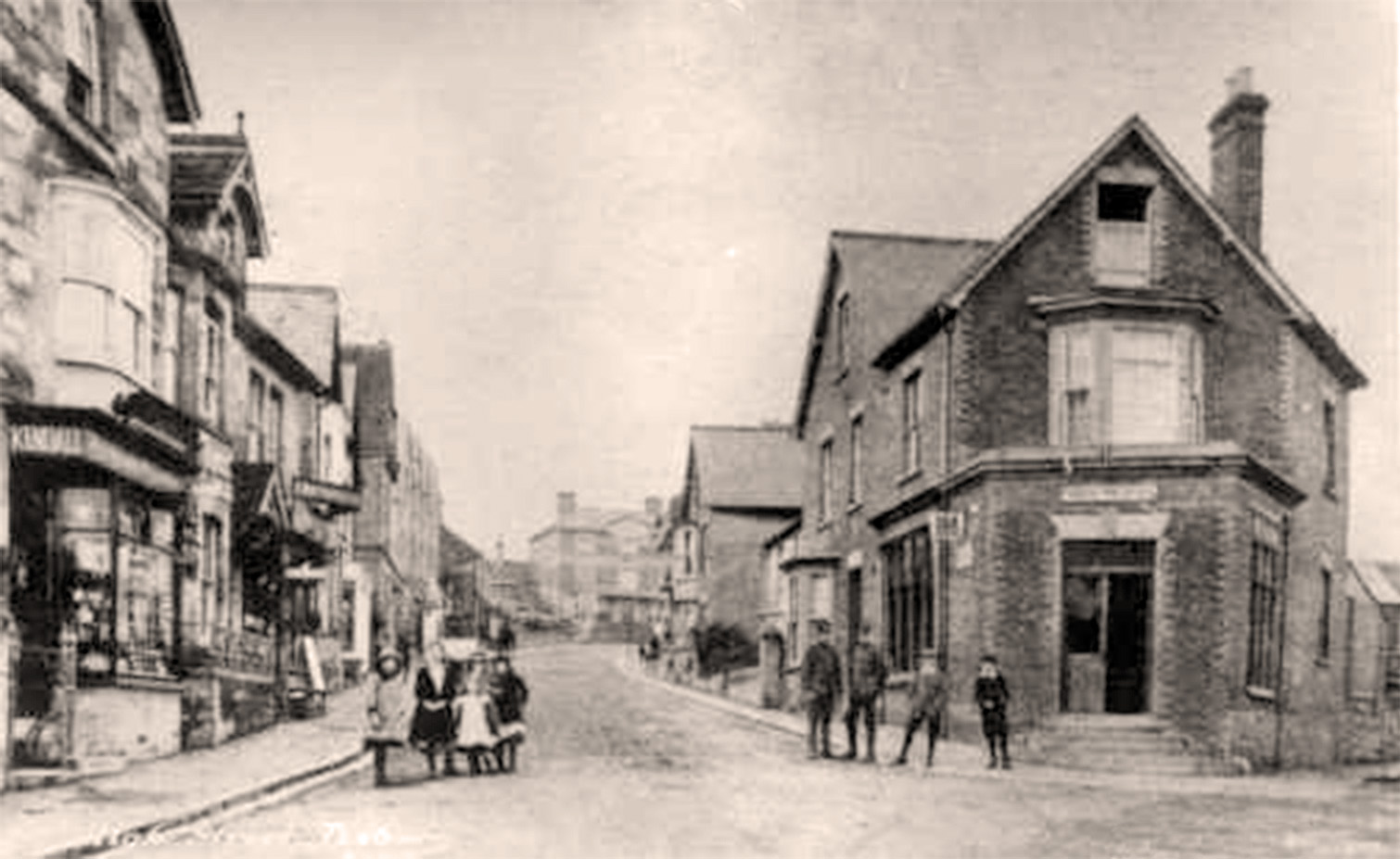

By 1910, the family had moved once again. This time Fred had been promoted to Police Sergeant and his new territory was Downton, Wiltshire—22 miles away, 5 miles south of the city of Salisbury. The family were living once again in the police station, which was situated on The Borough (see image, below)—the main street running through the part of the village on the west bank of the River Avon. It is here that we catch up with news of Frederick, and our focus now moves on to him.

The Borough, Downton. Copyright unknown

School Days

Although Frederick must have begun his education in Longbridge Deverill, no record has been found of this. His schooling after the move to Downton is recorded in the Bursary Log of his secondary school: The Bishop’s School, Salisbury (from 1911 the school was renamed Bishop Wordsworth’s School on the death of its founder).

Frederick’s primary school was Downton County School, only a few yards from his family home. His sister Dulcie had clearly applied herself in her studies and the 1911 Census tells us that she was a ‘School Teacher (Elementary)’ at the age of 17. It is likely that she was a pupil teacher, a role that she would have begun at the age of 15. She would probably have worked in the girls’ or infants’ school and had little contact with Frederick during his time in the boys’ school. Dulcie would eventually marry Alfred Ernest Barnes, a farm labourer from Bere Regis, Dorset, in 1923 (d.1972, Bere Regis). They settled in Wareham, Dorset and had one son, Randolph Barnes (b.1925 in Wareham, d.2005 Poole, Dorset). Dulcie’s occupation is recorded as ‘Unpaid Domestic Duties’ in the 1939 England and Wales Register. She died in 1968 in Bere Regis.

The school had been built in 1895 and was planned to accommodate 170 boys, 80 girls and 88 infants and in 1907 the average attendance was 120 boys, 54 girls & 48 infants. Frederick would have studied under the headship of John Northover, and assistant master John William Ford (Kelly’s 1907, p.241). Evidently, he excelled in his studies, and left the school in the summer of 1910 with a Wiltshire County Council bursary to attend Bishop Wordsworth’s School, Salisbury as a Day Scholar.

Bishop Wordsworth’s School. Public Domain. Original image by Ronald Thornton, derivative work by John Vickers

On Monday, 12th September, 1910, Frederick would have started out from home on the six-mile journey to his new school. Although the school was in the cathedral close, it was not one of the old-foundation grammar schools. A quick thumbnail history will give a taste of Frederick’s new surroundings:

The Bishop of Salisbury, John Wordsworth… set up ‘The Bishop’s School’ in a room in the Bishop’s Palace on 13th January 1890 – it was attended by just 45 boys. … Bishop Wordsworth personally donated £3000, which was used to purchase a portion of land in the Cathedral Close and build the original school buildings. … In July 1892 the school adopted its first Science Specialism… the Chemistry Lab was equipped that year too. The following year saw the erection of the Carpenter’s Shop… A new building including a Physics Lab and Lecture Room was added in 1897, swiftly followed by a Smith’s Forge and Workshop in 1900. … In 1902 the school became a Grammar School, consisting of the current Chapel Block, and Bishopgate. The number attended [sic] rose quickly from the initial 45 to about 90 in the Autumn of 1890, to 150 by 1900 and to over 600 by 1922. (Bishop Wordsworth’s School website)

Frederick’s diligence in his studies is evident in his examination successes: in 1915 he passed his Oxford Senior Local Examinations with honours and a distinction in French. We do not know which subjects this award covers: it was possible to gain the certificate by passing in five subjects, but eleven were covered by the curriculum: Arithmetic, English, Mathematics (Algebra, Geometry and Trigonometry), Higher Geometry, Latin, Greek, English History, Geography, French or German, Chemistry or Physics, and a portion of New Testament in Greek (Ackland, p.34).

On leaving Bishop Wordsworth’s on 31st July, 1915, Frederick shows that he had decided on his future career: teaching. He secured a position as a student teacher at Tisbury Church of England School. Tisbury, Wiltshire is twelve miles west of Salisbury and fifteen miles northwest of his family home in Downton. A student teacher’s post could be taken for a maximum of one year before going on to full-time teacher training at a recognised college. Frederick would begin his teaching career in the 290-pupil mixed school under the tutelage of the headmaster, John Freestone (Kelly’s, 1915), leaving on 31st July 1916 after having completed his year there. We note that in late 1916, Frederick’s next of kin was listed by the Army as his father, whose address was given as The Bennett Arms, Semley, Wilts, just three and a half miles southwest of Tisbury. It is not known when the family moved there nor if this overlapped with Frederick’s teaching at Tisbury. Unlikely as it may seem, Police Sergeant Fred was living in a public house while still working as a policeman. It is difficult to know whether this may have been a potentially compromising situation, or one of convenience: being on hand to deal with drunken behaviour! He was still being reported in the press as a policeman in 1920 (e.g. Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, Saturday 16 October 1920, p.7). An obituary of his wife, Louisa, in 1925 (Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, Saturday 14 March 1925, p.3. Her death was March 3rd.) shows they were still living at the Bennett Arms at that point and that Fred was an ‘Ex-P.S.’. Fred’s 1939 England and Wales Register entry lists him as a ‘Retired Police Sergeant’ and living in Trowbridge with his unmarried daughter Gwendoline.

Tisbury. Copyright Tisbury History Society. Used by permission

Frederick Doesn’t Go to War

We must return at this point to the newspaper article which began this story, and the statement: ‘from this school he entered Winchester Training College’. This looks straightforward, but the detail is somewhat less so. To explore this, we must take a lengthy detour through the effects that the war was having on Frederick’s situation, with particular reference to changes in recruitment policy and the world of teacher training.

Frederick was under-age until the end of 1915, by which time he had begun his work as a pupil teacher at Tisbury. Although teachers were in a reserved occupation and exempt from the draft, those training or about to begin training for the profession were not. But much had changed in the call-up process during this school year.

The Army needed around 92,000 recruits per month to replace losses. Towards the end of 1915 recruitment was running at around half this number. 1.5 million men were in reserved occupations and almost forty percent of volunteers were rejected for medical reasons. Enlisting in the Army had, until the end of 1915 been voluntary, although the Group System (also known as the Derby Scheme) in late 1915 was effectively a halfway house towards conscription. It is best described as being voluntary but coercive. It gave men a delayed and predictable entry into service rather than abrupt conscription, which many thought would very shortly be introduced. Derby Scheme men were placed on a reserve list and given an assurance that they would not be called up before a given future date. They were also given a day’s pay and an armband to wear in public to obviate accusations of cowardice or shirking. Even so, the scheme failed to elicit the numbers required. The Derby Scheme was closed about two weeks before Frederick’s eighteenth birthday when he reached military age. Officially, this precluded him from enlisting under the scheme although many of a similar age did so under-age by falsifying their dates of birth.

Within days of Frederick turning eighteen, Prime Minister Asquith introduced the Military Service Bill in Parliament to address the shortfall by introducing conscription. The Bill was Passed and given Royal Assent on 27th January 1916, coming into force on 2nd March 1916.

So, we have two possibilities: Frederick could have enlisted under-age through the Derby scheme. If he did not, he would be subject to conscription when it commenced in the Spring of 1916. Which route he took is somewhat academic as the Government had given the public an undertaking that young men would not be called until they turned 19. As we shall later see, he seems to have been called up on or around 10th November 1916, six weeks before his 19th birthday. The Army must have believed at this point that he was nineteen years old.

At some point, therefore, Frederick must have given a falsified date of birth. It is difficult to understand why he would ignore the opportunity to register under the Derby Scheme by posing as older, then wait until conscription before falsifying his date of birth by a few weeks. The circumstances would therefore suggest the Derby Scheme route as more likely, giving recruiters his date of birth as being on or before 10th November 1897. This also sits more easily with the newspaper’s ‘joining…as soon as he reached military age’—a difficult public statement to make in a local newspaper had he been conscripted when almost a year older than minimum age.

The Government amnesty for 18-year-olds left Frederick free to complete his year as a student teacher at Tisbury and begin teacher training—by this time the Anglican colleges took the view that students, even if their studies were to be interrupted by wartime service, could complete their course after the war.

The newspaper article reports one further detail: ‘joining the College Battalion…’. This is problematic. Winchester Training College students, with very few exceptions, joined a territorial unit at the beginning of their course—‘B’ Company of the 4th Territorial Battalion of the Hampshire Regiment. So, one would expect the 4th Battalion, Hampshire Regiment to be Frederick’s unit. However, 4th Hants had left England for India, landing there in October 1914, serving out the war in Mesopotamia, India and Russia. We know from Army documents that Frederick enlisted in Salisbury into the 14th (Service) Battalion of the Hampshire Regiment. The article’s ‘College Battalion’ comment is probably a reference to the Regiment—the Hampshire Regiment—rather than Battalion.

As the summer of 1916 and the end of his pupil teacher’s post approached, entry into training was open to Frederick, and becoming a student of Winchester Training College was his choice. We have not, however, done with the complexities of an England in wartime turmoil.

Winchester Becomes Battersea

The Anglican teacher training colleges had done more than their fair share of providing men for the war. In 1914 alone, the vast majority of its male students had volunteered for service, leading Osborne (see Souces below) to remark of Saltley College in Birmingham, ‘almost the whole college marched out of the main gate in August 1914.’ This is no hyperbole, as can be seen in the statistics from all training colleges (local authority and voluntary), listing the eight institutions—seven of which are Anglican—with the highest proportion of students serving in 1914 (Boyd):

| College | In Training 1914 | Enlisted 1914 | % |

| Battersea | 150 | 140 | 93.3 |

| Winchester | 80 | 74 | 92.5 |

| Bede (Durham) | 101 | 93 | 92.1 |

| Sunderland* | 69 | 62 | 89.9 |

| Culham (Oxon) | 92 | 81 | 88.0 |

| Exeter | 117 | 102 | 87.2 |

| Saltley (B’ham) | 110 | 93 | 84.5 |

| Chelsea | 136 | 105 | 77.2 |

| *local authority |

In August 1914, Winchester was the first college to close its doors for the duration of the war and it did so voluntarily at the very outset of the war. Almost all its students were now serving in the military, having been on Territorial Summer Camp on Salisbury Plain when war was declared. They were immediately mobilised. It must have been a strange experience for them as they were almost immediately billeted by the Army in the very buildings in which they had been studying. The remaining students (some of whom later enlisted, others were medically exempt) continued their studies under an arrangement with Bede College, Durham. Bede had a parallel experience to Winchester. In the summer of 1914, most of their students had been on territorial summer camp and were immediately mobilised, being drafted into the Durham Light Infantry. By becoming a gathering point for other colleges’ displaced students, it remained open for a further two years, closing at the end of term in July 1916. None of the memorial roll men studied at Bede. The fresh 1914 intake of twenty-four new students about to start their studies at Winchester, were transferred to Exeter Diocesan College. Among these students were two men on the memorial roll: William Richard Parsons and Charles Frank Singleton. Exeter college remained open for 1914–1915 academic year before closing in July 1915. The Winchester students who had begun their course in 1914 were then transferred to Bede College for their second (final) year. All remained as Winchester Training College students and were visited from time to time by WTC staff.

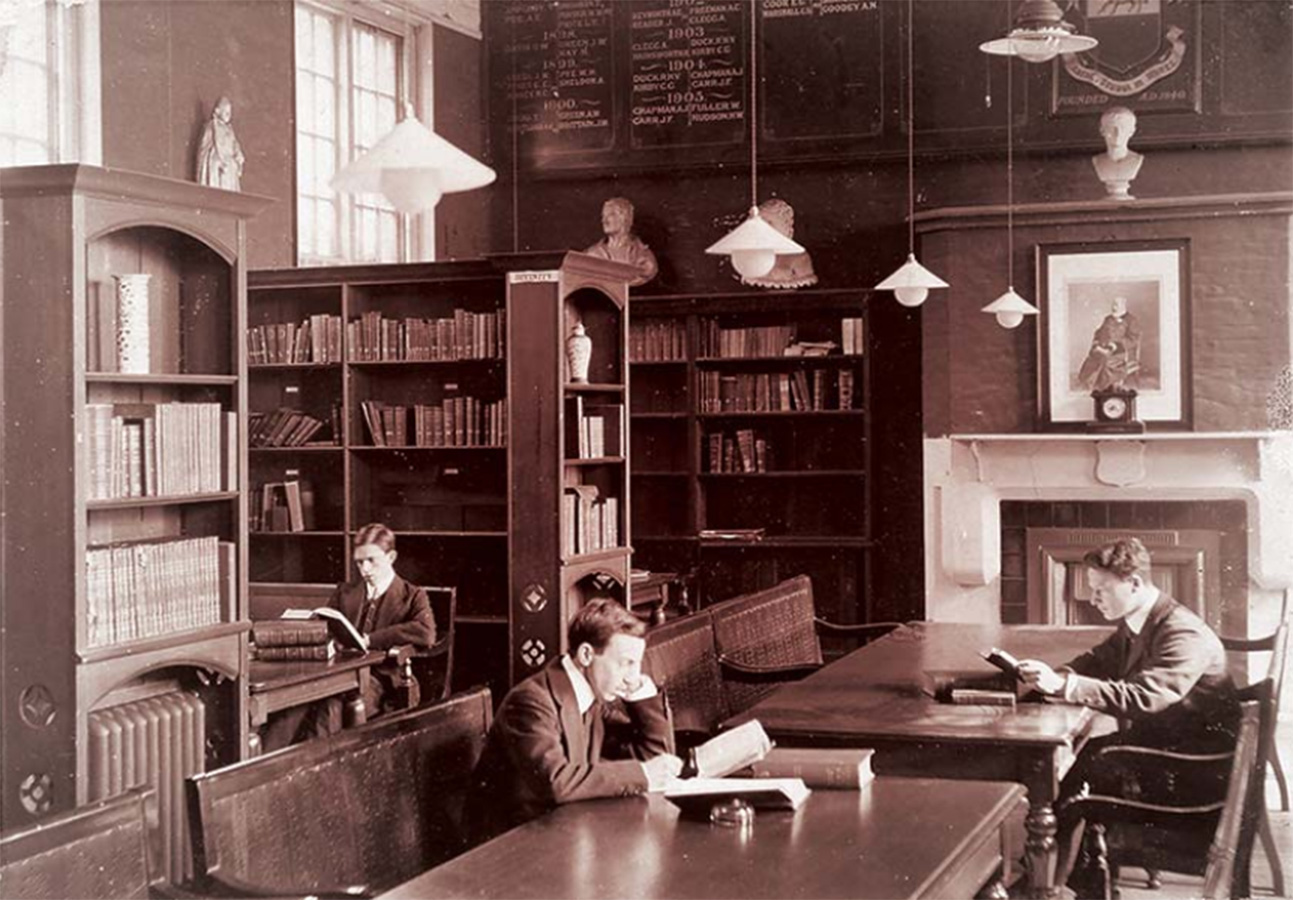

Other colleges met a similar fate: closure and dispersal of students to remaining colleges. The process, called Concentration, was overseen by the National Society (now known as The Church of England Education Office) in partnership with the Board of Education. The closure of a college was not compulsory, though any college remaining open would have to accept responsibility for its own finances and would not receive any compensation for losses incurred due to low student numbers. Effectively it was financially impossible to stay open and, in order to keep solvent and have any post-war future, colleges decided to close. Eventually, by the start of the 1916–1917 academic year, only St. John’s College Battersea remained open (the Battersea college eventually became, via a convoluted route, Plymouth Marjon University). It was here that all continuing and new students would be concentrated. They remained, as previously mentioned, students of their own, now mothballed, colleges.

The Library, St. John’s College, Battersea. Copyright Plymouth Marjon University.

Eventually we return to Frederick! Following his year as a student teacher in Tisbury, he entered training as a Winchester Training College student at Battersea. We have no details of his time there. Winchester records were considerably disrupted by the war and Battersea college archive does not carry a register of students from other colleges, as they were not their charge. However, Battersea’s archive lists eight Winchester students by name in its Teaching Practice Reports (Church, Mackrill, Noise, Price, Selby, Williams, Witts and Woolgar). It would have been surprising to find Frederick in this list: he was at the college for such a short time and would not have made it to his first teaching practice. College Reports, though, mention three Winchester students: two second-years (Price and Williams, again) and one first-year student, un-named as ‘he did not complete his year’. This fits Frederick’s circumstances precisely. Frederick and all of these students, although true Wintonians, would not have set foot on the Winchester campus.

Frederick’s War

Frederick’s main military records were destroyed during the Blitz in the Second World War, so we can only reconstruct his Army service indirectly. Those documents that exist, which were stored separately and therefore survived, are his Medal Roll Index Card, the related Service Medal and Award Roll, a Hospital Admission Register and the Army Register of Soldiers Effects.

Frederick enlisted in the 14th (Service) Battalion of the Hampshire Regiment in Salisbury and was given the Regimental Number 27745. Although we don’t have a date for this, his number was issued as part of a series. As number 27740 was issued on 10th November 1916, it is likely that he joined on that day or perhaps a day later. His hospital record of late September 1917 tells us that he had been serving in the Army for ten months, which accords well with this extrapolated date. We can therefore see that his time at college was short. He must have been given leave by the college—which encouraged students to enlist—to travel home to bid his family farewell before enlisting.

Copyright unknown

He then would have spent time training before being sent to join his Battalion—also known as the 1st Portsmouth Pals—on the Western Front in January 1917. His training was therefore slightly shorter than the usual twelve weeks, a sign of the pressure the army was under at this point of the war.

The Battalion was at Ypres and had been so since early December. Compared to many of the infantry units which moved from battle to battle, in 1917 14th Hants had a settled though not a quiet existence. The Battalion War Diary records day by day the main activities of the men and lists the places they served from January through to September. A lot of the work they did in the trenches was simply logged by terse generic terms such as ‘Working Parties’, ‘Advanced Parties’ and ‘Specialists’, but specific tasks included: setting barbed wire entrapments, repairing duckboards, observation, improving new HQ, filling sandbags, completing dugouts, clearing blown-in trenches, reconnoitring, carrying parties, raiding parties, pushing parties, digging trenches, etc. After listing these mundane tasks, it is important to note that although the Battalion title includes ‘(Service)’, it was a normal fighting unit. The ‘(Service)’ term simply indicates that it was part of the New Army (or Kitchener’s Army)—born out of Kitchener’s insistence on the need to place new volunteers or recruits into new Battalions of men rather than trying to add them in to existing regular or territorial Battalions.

Frederick’s war was fought entirely in the Ypres salient. From January to the end of July the British Army were engaged in holding the line. On 31st July, the great Paschendaele offensive— also known as the Third Battle of Ypres —began, and Frederick would have been caught up in this muddy, bloody maelstrom. On the opening day his Battalion were involved in a full attack in the Hill Top Sector, going over the top at 3.50am. Casualties were, Officers: 3 killed, 2 wounded; Other Ranks: 18 killed, 156 wounded, 42 missing. The enemy trenches were taken, and the following were captured: 2 field guns, 1 4½” howitzer, 17 machine guns, 200 prisoners.

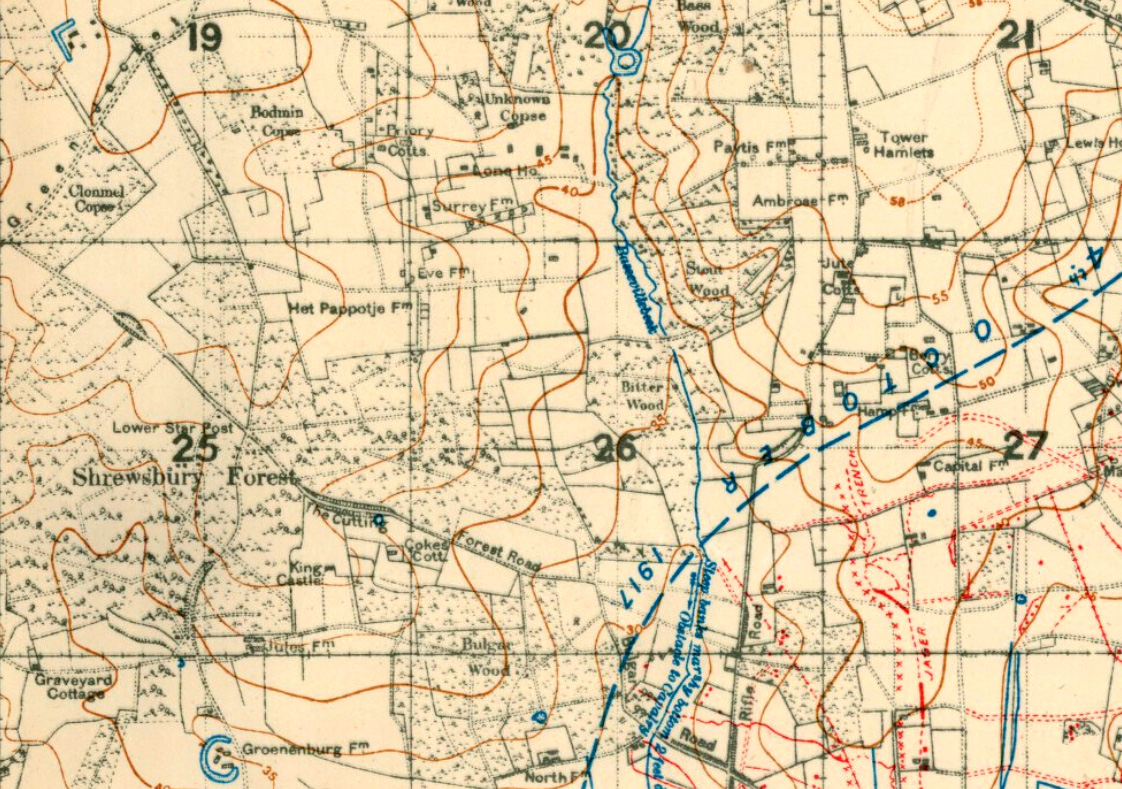

Places listed in the diary when Frederick’s unit were in the trenches are: Kruisstraat, Observatory Ridge, Zillebeke, Bund, Canal Bank, Hilltop Sector, Wormhout, Wieltje, Houlle, and Hollebeke.

By mid-September 14th Hants were active in the Shrewsbury Forest area of the Ypres front. On the 16th we read a seemingly strange entry:

Fairly quiet day. Some gas shells over during the night. Casualties: 30 Other Ranks Killed, 6 Wounded.

The contradiction of the Battalion suffering so many losses on a ‘fairly quiet’ day is a telling comment on perceptions of life at Paschendaele. However, the main point we take from this diary note is the enemy’s use of gas shells. This is not by any means the first mention of the use of gas, but it is significant for Frederick. Although diaries vary in how they report casualties, the 14th Hants listed gas casualties as a separate item, so we note that in this instance there were no men affected by these shells.

The gas used against allied troops at Paschendaele was new to warfare: Mustard Gas—sometimes known as Yellow Cross from the markings on the shells. First used in July, its effects were terrible: exposed skin was blistered, eyes became very painful and vomiting would begin. The gas caused internal and external bleeding and damaged bronchial tubes, stripping away mucous membranes. A painful death could sometimes take four or five weeks. A nurse, Vera Brittain, wrote: ‘I wish those people who talk about going on with this war whatever it costs could see the soldiers suffering from mustard gas poisoning. Great mustard-coloured blisters, blind eyes, all sticky and stuck together, always fighting for breath, with voices a mere whisper, saying that their throats are closing and they know they will choke.’

Aerial photograph of Shrewsbury Forest. Date 7 July 1917. IWM image Q 55511. The term ‘Forest’ is misleading. By this point in the conflict this hilltop forest had been completely denuded of trees, with only shattered stumps and trunks remaining.

Casualty rates would increase through the month: from 16th to the 27th the diary reports: 80 Killed, 148 Wounded, 1 Died of Wounds, 30 Missing, 5 Gassed. This makes a total operational loss of 264—greater than one in four of the Battalion.

We will follow the diary verbatim through the last six days of Frederick’s life:

September 22 (Night), Cottage Camp: Battalion moved up to Shrewsbury Forest and relieved 15th Hants and 11th Queen’s in line. A Company front line, 2 Platoons of B Company in immediate support, C Company main support, and remaining 2 Platoons B Company and D Company in reserve. Casualties: 3 Wounded Other Ranks.

September 23, Shrewsbury Forest: Heavy shelling by enemy during the early morning, intermediate intermittent shelling during day. Casualties 2nd Lieutenant AJR Clarke Wounded, 6 Killed 22 Wounded.

September 24, Shrewsbury Forest: Relieved during night of 23rd / 24th by 12 Royal Sussex Regiment in front line and supports and the 11th Sussex in reserve. Two Companies only in each Battalion. Casualties 2nd Lieutenant FW Charting Wounded. Returned to Cottage Camp (Night) except C Company. The latter remained at Hedge St. Tunnels to form dumps and provide carrying parties.

September 25, Cottage Camps: Battalion moved out of camp up to Shrewsbury Forest sector and took up assembly positions in front of 11th Battalion Royal Sussex Regiment.

September 26, Shrewsbury Forest: Battalion attacked at 5.50 AM. First objective being Tower Hamlets and second objective Tower Trench. Heavy casualties through machine gun fire. Objectives were reached and held and consolidation carried out on our side of Tower Trench. Casualties: Major Goldsmith Died of Wounds, Killed: Captain T.R. Nichols, Lieutenant Bainbridge, 2nd Lieutenant B.G. Wilson, Wounded: 2nd Lieutenant H.P. Sangster, 2nd Lieutenant R.N. Butt, 2nd Lieutenant Barras, 2nd Lieutenant Thomas. Other ranks 41 Killed, 113 Wounded, 30 Missing. Heavy shelling and sniping by enemy all day.

September 27, Shrewsbury Forest: Very quiet morning. Shelling by enemy during the afternoon which slackened at night. Casualties: Other Ranks Killed Nil, Wounded, Nil, 5 Gassed. Relieved by 13th Royal Fusiliers in front line. 13th KRR in Support line.

Frederick was one of the five men who were gassed on the 27th September. Initially he probably would have received rudimentary care and assessment at a Regimental Aid Post, usually in a communication trench. Hospital records show that he was placed in a sick convoy before being transferred to 133rd Field Ambulance medical unit the following day, then on to No. 11 Casualty Clearing Station at Godewaersvelde, where he died on the 29th.

Four others of the 14th (Service) Battalion Hants were gassed with him: Pte. Edwin Albert Pitman 242657, Cpl. G.H. Pink 17518, Sgt. F. Videan [text uncertain] 8008, and C.Sgt. R Cooper 4944. Of these, only Private Pitman died, also on the 29th.

Frederick was laid to rest in Godewaersvelde British Cemetery, France, close to the Belgian border. He was survived by his mother, father and three sisters.

He is also remembered on the following memorials: Bishop Wordsworth’s School Memorial; Tisbury Village Memorial; St. John the Baptist Church Memorial Plaque, Tisbury. His name does not appear on the memorial roll of Plymouth Marjon University or the Winchester University/Winchester Training College memorial.

Sources

Ackland, A.H. Dyke (1911). Report of the Consultative Committee on Examinations in Secondary Schools. London: HM Stationery Office.

Ancestry (2018). Home page. [online] Available at: www.ancestry.co.uk [Accessed 25 June 2018].

Bishop Wordsworth’s School (2018). BWS – 126 Years of history in one webpage. [online] Available at: http://www.bws-school.org.uk/The_School/History/ [Accessed 25 June 2018].

Boyd, Michael V. (1981) The church colleges 1890-1944. Durham: Durham University. [online] Available at: Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7517/

British Newspaper Archive (1902). Warminster & Westbury journal, and Wilts County Advertiser, Saturday 10 May 1902, p.8. [online] Available at: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001558/19020510/138/0008 [Accessed 25 June 2018].

British Newspaper Archive (1904). Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, Saturday 20 August 1904, p.5. [online] Available at: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001557/19040820/081/0005 [Accessed 25 June 2018].

British Newspaper Archive (1904). Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, Saturday 3 September 1904, p.8. [online] Available at: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001557/19040903/136/0008 [Accessed 25 June 2018].

British Newspaper Archive (1917). Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser – Saturday 27 October 1917,p.12. [online] Available at: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001557/19171027/158/0012 [Accessed 25 June 2018].

British Newspaper Archive (1920). Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser – Saturday 16 October 1920, p.7. [online] Available at: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001557/19201016/215/0007 [Accessed 29 June 2018].

British Newspaper Archive (1925). Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser – Saturday 14 March 1925,p.3. [online] Available at: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001557/19250314/064/0003 [Accessed 25 June 2018].

Brittain, Vera (1933). Testament of Youth: An Autobiographical Study of the Years 1900–1925. New York: The Macmillan Company.

Elsworth Chronicle (2015). A village policeman, 1912. [online] Available at: http://www.elsworthchronicle.org.uk/Elsworth%20People/People10.html [Accessed 28 June 2018]

FindMyPast (2018). Bishop Wordsworth’s School Bursary Log. [online] Available at: https://www.findmypast.co.uk/ [Accessed 25 June 2018]

Great War Forum, (2018). Frederick William Randolph, 14th (Service) Battalion, Hampshire Regiment – John Vickers. [online] Available at: https://www.greatwarforum.org/topic/261791-frederick-william-randolph-14th-service-battalion-hampshire-regiment/?tab=comments#comment-2652437 [Accessed 2018].

Hey, D. (1997) The Oxford dictionary of local and family history. Oxford: Oxford university Press.

HMSO (1921) Soldiers Died in the Great War 1914-1919. London: HMSO

Imperial War Museum (2018). Aerial photograph of Shrewsbury Forest, no 7819, Sheet 28.1.30. Date 7 July 1917, Q 55511. [online] Available at: https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205305167 [Accessed 2018]. Kelly’s Directory (1907).

Kelly’s Directory of Wiltshire, 1907, p.241. [online] Available at: http://specialcollections.le.ac.uk/cdm/ref/collection/p16445coll4/id/339948 [Accessed 25 June 2018]. Kelly’s Directory (1915).

Kelly’s Directory of Wiltshire, 1915, p.245. [online] Available at: http://specialcollections.le.ac.uk/cdm/ref/collection/p16445coll4/id/352363 [Accessed 25 June 2018].

Lidgitt, P. and Naylor, P. Cemetery photographs.

National Library of Scotland (1900) Wiltshire VIII.15 (Lea and Cleverton; Malmesbury St Paul Without; Malmesbury) Revised 1899. [online] Available at: https://maps.nls.uk/view/124880919 [Accessed 25 June 2018] National Library of Scotland (1917) British First World War Trench Maps, 1915-1918, 28.NE Scale: 1:20000 Edition: 8A, Trenches corrected to 1 October 1917. [online] Available at: https://maps.nls.uk/view/101464912 [Accessed 28 June 2018]

Osborne, J. (ed.) (1950) Saltley College Centenary, 1850-1950. Birmingham: Saltley College

Rose, M. (1981). A history of King Alfred’s College, Winchester 1840-1980. London: Phillimore.

Tisbury History Society (2018). Tisbury History Society, The Post Office, Tisbury. [online] Available at: http://www.tisburyhistory.co.uk/picpages/po.html [Accessed 28 June 2018].