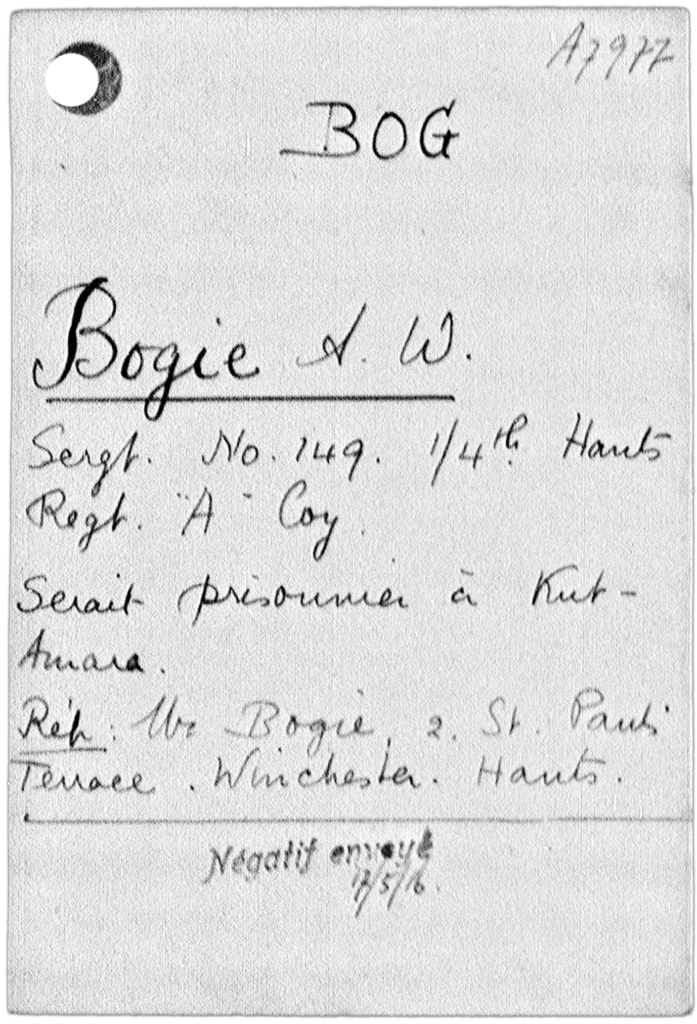

Sergeant Andrew Bogie, Regimental Number 200023, of the1/4th (T.F.) Battalion Hampshire Regiment, died of illness, aged 34, in Yarbaschi (now Yarbashi, Turkey), as a Prisoner of War, on the 22nd September 1916.

Family Background

Andrew was born in 1882 in Guernsey in the Channel Islands. His parents were Peter Kerr Bogie, who had been born in Scotland, and Catherine Bogie who was a British Citizen but born in Malta. Andrew was their first child. In the 1891 census the family was living in Croydon and Peter was working as a gardener and domestic servant. By this time nine year old Andrew had a younger brother Alfred (6) and a sister, Catherine (4). Alfred had, like Andrew, been born in Guernsey, but Catherine was born in Bracebridge near Lincoln. By 1901 the family had moved again, this time back to Guernsey, where Peter was a self-employed fruit grower. Andrew, at 19, was working as a school teacher and his younger brother was following in his father’s footsteps as a gardener. By the 1911 census, Andrew was a married man, living at 11 Highfield Villas, Winchester with his new wife Florence Hannah (née Moss). Florence had been born in 1887 in Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, to Martin, a brewer’s cooper, and Hannah. Andrew was a Certified Elementary Schoolmaster, working in the Practising School in Winchester, St. Thomas’. Andrew and Florence had been married in the summer of the previous year. On the 23rd February 1913 Andrew and Florence had a son, Kenneth Andrew.

Training and Teaching

Andrew attended Winchester Training College from 1902 to 1904. In the College magazine it was noted that Andrew Bogie often took part in debates including one that asked Would conscription be beneficial to the country? He played in the reserves football team. He was part of the Volunteer Company that all the students joined on entry to the College. In the magazine it was reported that he was promoted to Corporal. Former Principal and college history author Martial Rose gives us an insight into aspects of life in College at the time that Andrew attended: Prior to 1904 the food provided for students was meagre. Breakfast and tea consisted of a small pat of butter with a hunk of bread and some tea. If students provided their own oatmeal they were allowed porridge and if they brought in an egg with their name on it, they could have that boiled.

After he left College Andrew got a job in St Thomas’s School, the Practising School in Winchester. As this was the school that the Training College used to instruct the student, it can be assumed that Andrew was a better than average teacher. He would have been required to give demonstration lessons to the College students.

From Schoolmaster to Soldier

Andrew joined the Hampshire Regiment and as part of the 1/4th (Territorial Force) Battalion he was deployed to Mesopotamia. In that Battalion were others who had done their teacher training in Winchester. The Battalion landed at Basra with the 33rd Indian Brigade. With oil interests in the area Mesopotamia was of considerable strategic value. A full account of this part of the conflict is available here. With Basra secure the troops advanced towards Baghdad, capturing Nasiriyeh and Kut-al-Amara. An attempt to capture Ctesiphon (pronounced Tessifon) failed and the force retreated to Kut-al-Amara where they had accumulated supplies for the proposed advance on Baghdad. They were pursued by Turkish troops during their retreat and decided to stay in Kut and defend the town.

From 7th December 1915 until 29th April 1916 Kut al Amara was besieged by the Ottoman Army. Inside the town were roughly 20,811 people, including many of the local citizens, the sick and wounded and a fighting force of about 13,000 British and Indian soldiers. In the course of the siege they were subjected to sniper fire, ground and aerial bombardment and intermittent assaults on their frontline defences from Turkish troops. Weather conditions were appalling both in extremes of heat and incessant rain causing flooding. They were plagued by insects and sand storms. Disease and illness were rife and as the siege wore on rations were running out and the men were daily closer to starvation. It was under these dreadful circumstances that Andrew Bogie impressed his Commanding Officer sufficiently to be mentioned in dispatches and to be awarded the Military Medal. In The London Gazette of 19th October 1916, from The War Office, The Government of India has received from Lieutenant General Sir Percy Lake the following list of names of officers and others recommended by Major-General Townshend for distinguished service during the defence of Kut-al-Amarah. Among those mentioned was ‘Bogie, Acting Co Qrms-Serjt A.W.’

His Military Medal was not gazetted until 1919, but was again in reference to the defence of Kut. In The London Gazette of 21st October 1919:

His Majesty the KING has been graciously pleased to approve the award of the Military Medal to the undermentioned Warrant Officers, Non-Commissioned Officers and Men for bravery in connection with the defence of Kut-al-Amara. Hampshire Regiment 149A CQM Sjt Bogie A W 1/4th Bn T.F. (Winchester).

On 29th April 1916, the Garrison within Kut surrendered to the Turkish Commander, and for Andrew, as well as all the other men, another terrible ordeal began. As Prisoners of War they were marched over long distances, with little or no regard paid to their physical condition, with inadequate food and water and under the control of guards who treated their suffering with indifference or cruelty.

On 6th May 1916, the Turks began the 1200 mile forced march of the British and Indian prisoners across the Syrian Desert from Kut. Mounted Arab and Kurdish guards prodded over 2500 British soldiers with rifle butts and whips on the long death march. Starvation, thirst, disease and exhaustion thinned out the British column, and only 837 soldiers survived the march and the years in captivity.

Kenneth Steuer, Pursuit of an Unparalleled Opportunity

The Other Ranks suffered particularly harsh treatment. An illustration of the way the prisoners were treated can be found in a letter written by RSM Leach (also an alumnus of Winchester Training College), about Private Woods of the 1/4th Hants. This extract also shows that Andrew Bogie had become sufficiently proficient in the Turkish language to act as an interpreter:

During the march on the night of 12th-13th June, Pte Woods who had considerably fallen away through weakness fell out on the march. On arriving at the rest camp on the morning of the 13th Pte Woods was missing. After about an hour after arrival it was reported to me that a man of the Hants Regt was lying helpless close to where the camels were unloaded. I had the man fetched and on being brought to me found him in an utterly exhausted condition. His belt had been stolen by the escort, and his shirt was very much torn. His body was one mass of scars and bruises which he accounted for by the brutal treatment he had suffered. He was flogged and kicked and hit with rifles and was absolutely unable to pick out or recognise the man who had treated him this way owing to his weak condition. I took him with Coy. QM Sgt Bogie (acting as interpreter) to Kashmi Effendi, and showed him how the man had been treated , but owing to the man not being able to pick his assailants no visible sign of notice seemed to be taken. Pte Woods died a short time later.

In general, the Turks did not follow Western rules and regulations in dealing with war prisoners. Captured soldiers were herded like sheep by mounted Arab troopers who freely used sticks and whips to keep stragglers marching. Food was very scarce, and the POWs rarely had access to fresh water. The desert climate where most of the campaigning took place had a debilitating impact on prisoners, especially the heat and dust. Often Turkish troops and guards relieved captives of their water bottles, boots and uniforms, leaving the POWs in an assortment of rags—Ottoman officers exercised very little control over their men. When prisoners collapsed exhausted, starved or ill, many were left to fend for themselves in hovels. These mud-walled “shelters” were often filled with vermin and soldiers had to resort to begging from passing Arabs for scraps of food. Many of these invalids were robbed, stripped of their last clothing and left to die. After marching across the desert, the remaining POWs entered prison camps where they received insufficient food and faced epidemics of dysentery, cholera and malaria.

Kenneth Steuer, Pursuit of an Unparalleled Opportunity

We know very little of Andrew Bogie’s time in captivity once he reached his destination. Mrs Bowker, the widow of the Battalion C.O., arranged for parcels, containing essential supplies, to be sent to the prisoners. Her records show that he was adopted by the Stilwells of Windlesham, Surrey. Each prisoner was supported by financial contributions from an individual or family, arranged by Mrs Bowker. The parcels contained replacement clothes as many of the prisoners had lost essential items both through theft and bartering for food. They also received the occasional treat such as a football or pack of playing cards and at Christmas a plum pudding was sent. The other thing we learn from Mrs Bowker’s fund ledger is that Andrew Bogie was 5’10” with size 9 feet and his cap size was 6¾.

Disease and illness was unfortunately part of the everyday life of the prisoners and Andrew eventually succumbed to dysentery at Yarbaschi on the 22nd September 1916. It is interesting to note how news of Andrew’s death was announced. It arrived through a communiqué from the Dutch legation in Constantinople.

The Netherlands Minister at Constantinople presents his compliments to his Brittanic Majesty’s Minister at the Hague and has the honour to report that the following information regarding certain British prisoners of war has been received from the Ottoman Red Crescent Society under date of the 24th instant.

The date at the bottom of the communique was 29th January 1918. It gave no details of the cause or place of death for Andrew although it does for some of the other prisoners mentioned. We do not know if this was the first notification of Andrew’s death to reach home.

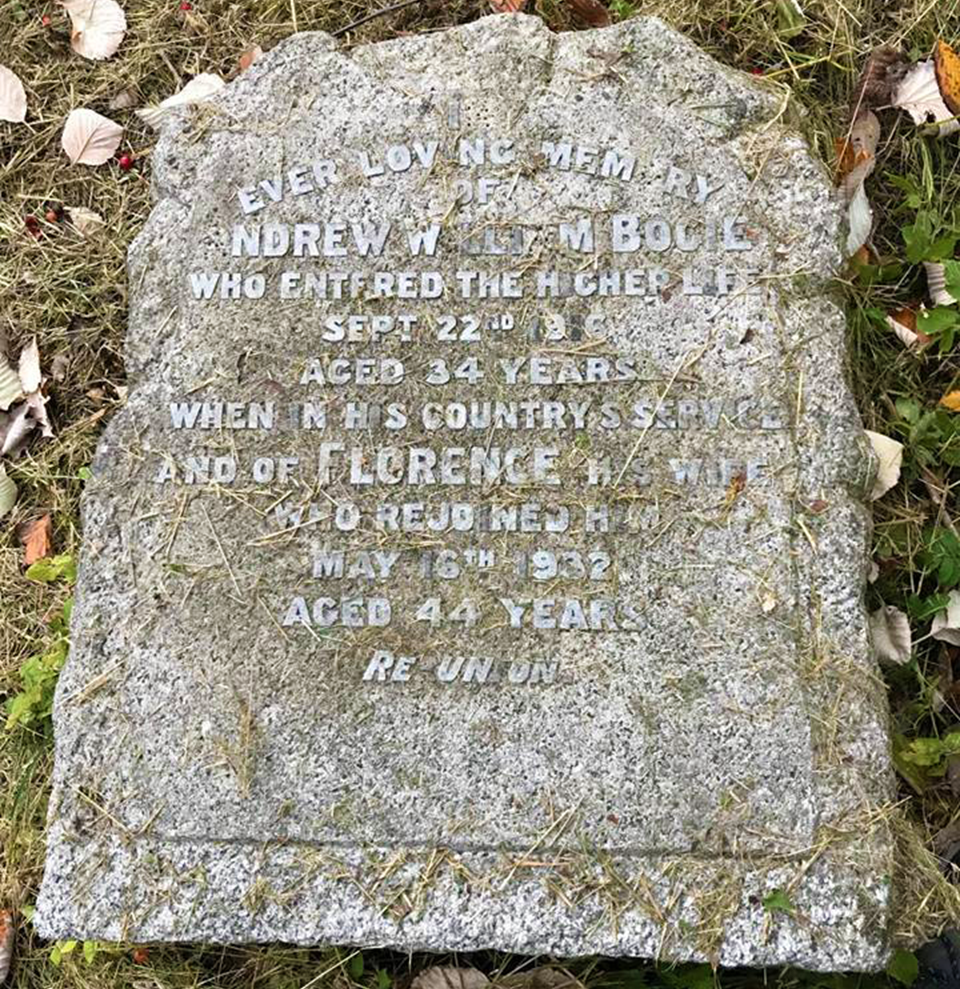

He is buried at North Gate War Cemetery in Baghdad (Plot XXI Row R Grave 21). He is also commemorated at King’s School in Winchester on a memorial originally in St. Thomas’ School, and in the town of his birth, St. Peter Port in Guernsey.

Probate records show that he left £137 19s 11d to his widow Florence, who was living at 22, St. Paul’s Hill, Winchester, with their three year old son.

Researcher and Author: Dee Sayers

Sources

For all general Winchester training College records please see the list of University of Winchester sources at the end of the following Sources list.

Ancestry (2018) Records, and Michael Moss family tree. [online] Available at: www.ancestry.co.uk [Accessed 2018]

Commonwealth War Graves Commission, (2018). Home page. [online] Available at www.cwgc.org/ [Accessed 2018]

Crowley, P. (2016). Kut 1916: the forgotten British disaster in Iraq. Stroud: The History Press

Great War Forum, (2018). Home page. [online] Available at www.greatwarforum.org [Accessed 2018]

Guernsey Roll of Honour. (2016). Home page. [online] Available at: www.roll-of-honour.com/

Guernsey/StPeterPort.html [Accessed 2018]

Hampshire War Memorials. (2018). Home page. [online] Available at hampshirewarmemorials.com [Accessed 2018]

The London Gazette. (2018). Home page. [online] Available at www.thegazette.co.uk [Accessed 2018]

The Long Long Trail, (2018). Welcome to the long long trail. [online] Available at http://www.longlongtrail.co.uk/ [Accessed 2018]

The National Archives. POWs in Turkey, FO 383/456. London

Rose, M. (1981) A history of King Alfred’s College, Winchester 1840-1980. London: Phillimore

The Royal Hampshire Regimental Museum archives, Serles House, Southgate St, Winchester SO23 9EG

Vickers, J. The University of Winchester Chapel Memorial Rail image

Steuer , K (2014) Pursuit of an unparalleled opportunity [New York]: American Council of Learned Societies

University of Winchester Archive at Hampshire Record Office

All the following documents are general background resources for the WTC Fallen project and provide general period background of students, college life, staff, activities, etc. The Finding Numbers are given to aid archive searches.

47M91W/P2/4 The Wintonian 1899-1900

47M91W/P2/5 The Wintonian 1901-1902

47M91W/P2/6 The Wintonian 1903-1904

47M91W/P2/7 The Wintonian 1904-1906

47M91W/P2/8 The Wintonian 1905-1907

47M91W/P2/10 The Wintonian 1908-1910

47M91W/P2/11 The Wintonian 1910-1914

47M91W/P2/12 The Wintonian 1920-1925

47M91W/D1/2 The Student Register

47M91W/S5/5/10 Photograph of 5 alumni in Mesopotamia

47M91W/Q3/6 A Khaki Diary

47M91W/B1/2 Reports of Training College 1913-1914

47M91W/Q1/5 Report and Balance Sheets 1904- 1949

47M91W/R2/5 History of the Volunteers Company 1910

47M91W/L1/2 College Rules 1920

55M81W/PJ1 Managers’ Minute Book 1876-1903

71M88W/6 List of Prisoners at Kut

All material referenced as 47M91W/ is the copyright of The University of Winchester. Permission to reproduce photographs and other material for this narrative has been agreed by the University and Hampshire Record Office.