Preface

I would like to begin on a personal note. I hope this is not over-indulgent. The name of Ypres was my first childhood awareness of the Great War. The scene was mundane and domestic: a 1960s Sunday afternoon extended-family tea in a Durham miner’s cottage. The table talk was desultory and trivial, at one point stumbling into the subject of car windscreen wipers. During this my grandfather interjected, ‘We used to call Ypres, Wipers.’ The conversation did not change tack and blithely continued its inconsequential course. I later became aware that the adults present knew better than to intrude further on his dark reverie. This was the only time he spoke of his experience of the war. My father, his only son, knew nothing of his wartime service. Over fifty years later I was to discover through research that he, as a young man of nineteen, fought at Ypres as a sniper in the hell known as Passchendaele.

Ypres saw not one battle but five. The third (Passchendaele) is infamous. It became synonymous with mud and slaughter on a par with and even exceeding that of the The Somme. The final two battles are rarely called by their numbered Ypres battle names but the thread common to all of these battles is clear in the memories etched in the minds who were there:

It was mud, mud, everywhere: mud in the trenches, mud in front of the trenches, behind the trenches. Every shell hole was a sea of filthy oozing mud. I was tired of seeing infantry sinking back in that morass never to come out alive again. I was tired of all the carnage, of all the sacrifice that we had there just to gain about twenty-five yards. And there were many days when actually I don’t remember them; I don’t remember what happened because I was so damned tired. The fatigue in that mud was something terrible. It did get you and you reached a point where there was no beyond, you just could not go any further. And that’s the point I’d reached.

John Palmer, British Gunner

The Flanders mud received the bodies of eleven of our Wintonian boys. The first four battles took the lives of seven alumni, while the mud-fields of Flanders around Ypres received another four in the hiatuses between the battles.

Introduction

The Great War began with Germany’s invasion of Belgium. As France’s eastern border was heavily fortified and defended, the Schlieffen Plan was to sweep into France at speed through the north by invading Belgium and in so doing violating its neutrality. This succeeded in its early phase but ground to a halt at the Battle of the Marne in early September. A disaster had been avoided by the retreating French forces being supplemented by recruits and men taken from the eastern front, and the doughty resistance of the professional pre-war trained British Expeditionary Force (BEF, later to be known as The Old Contemptibles). The regathered and augmented Entente forces now outnumbered the German army who in turn were exhausted after a full month of actions and had outrun their supply and communication lines. The Schlieffen plan’s expectation of total victory over France in 40 days lay in ruins.

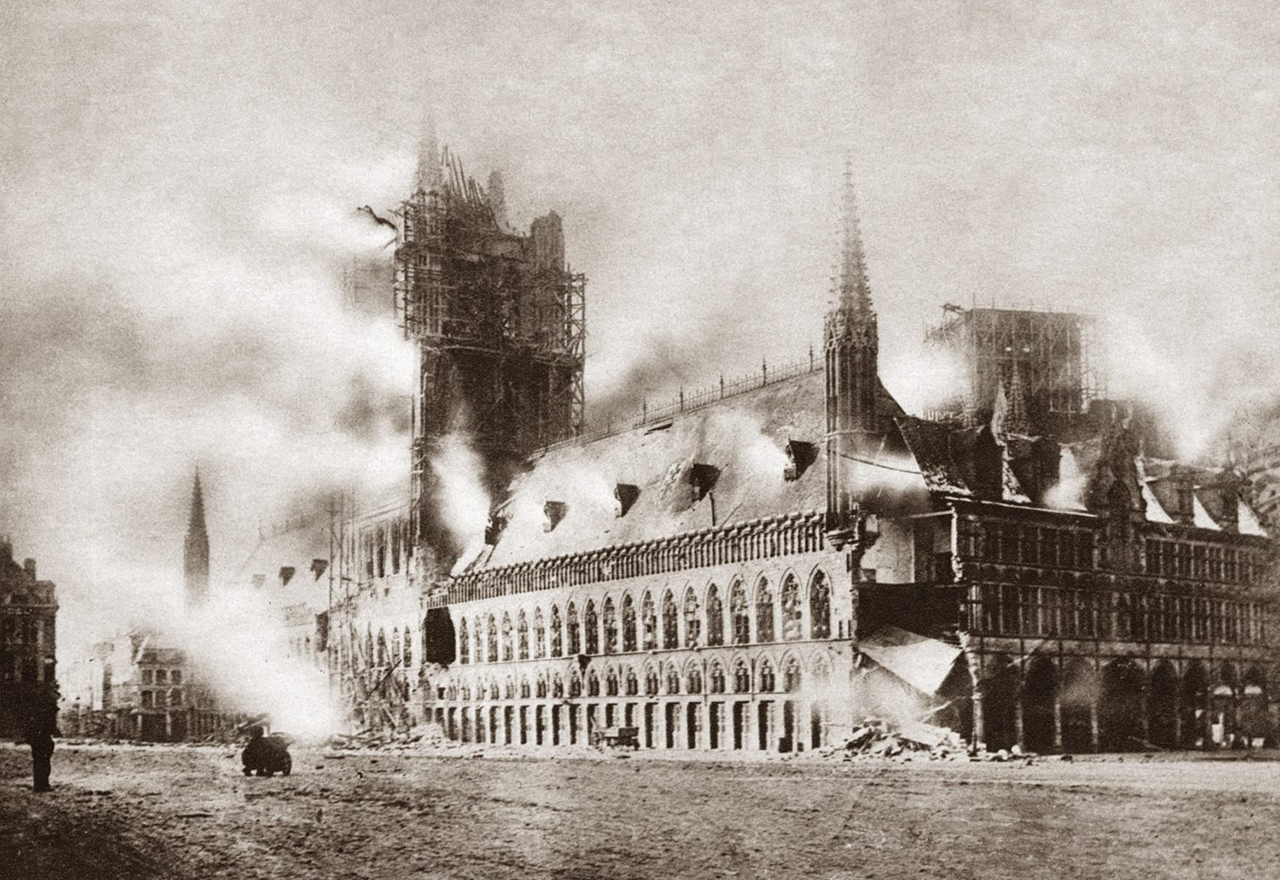

The Franco-British and German armies now made repeated moves to outflank one another to the north, with each attempt and its counter driving the conflict to the northwest through the provinces of Picardy, Artois and Flanders. Known as The Race to the Sea, the outflanking moves ended on the coast with armies facing one another but with neither having gained an overall advantage. After reaching the North Sea, both armies carried out offensives: the Battle of the Yser from 16 October to 2 November, and the First Battle of Ypres. Ypres became a focal point of the campaign due to its geographic location and importance as a transportation hub.

The First Battle of Ypres (19 October – 22 November 1914)

In October, German forces began a major offensive to advance to Dunkirk and Calais. This necessitated taking the town of Ypres. The German Fourth and Sixth Armies faced the French VIII Army, the BEF and the Belgian Army. Strategically, Ypres was difficult to defend as it was a salient—surrounded on three sides by the enemy. It was also overlooked by higher ground which rose in an arc around the city from one o’clock to seven o’clock positions: the Messines, Kemmel and Wytschaete ridges. The lower ground was also very wet, with a high water-table, making deep trenching systems impossible.

When you got up there, there was no front line; there was no line at all, just a series of posts scraped in the mud. Here a machine gun’s crew, there a few riflemen, further on a Lewis gun’s crew and in some cases the battle depth of your battalion was a thousand yards of these posts bogged about. You couldn’t get to any of them in daylight, because you were under enemy observation the whole time. You couldn’t get food nor rations nor ammunition or anything up in the daylight, because these duckboards were taped by the Germans and they were shelling them the whole time. In most places, if shells start dropping you run to the right, you ran to the left and to get some cover but if you were on the duckboards you couldn’t run. There was mud to your right and mud to your left and you had to face it and go on.

Richard Tobin, British NCO

This became worse as the conflict wore on: shelling the area destroyed the natural and artificial drainage resulting in waterlogged ground and endless mud. It became virtually impossible to recover or bury the dead, whether man or beast, and the stench from putrefaction was heavy in the air. At one point in the battle, the ground conditions were used as a defence. Hard-pressed Belgian troops near the coast prevented a German breakthrough by opening tidal sluices to flood the land and hinder movement. The shallow trenches of Flanders may have provided cover against small-arms but they gave scant protection against artillery. However, as would be played out time and again in the war, First Ypres demonstrated that attacking dug-in positions, however meagre, was a costly affair. Even with numerical superiority and excellent artillery, the enemy was unable to take the town.

The conflict was confused but bitter. Despite the poor protection afforded by the defences, the German forces struggled to gain any advantage over the defending allies. Despite numerical superiority and excellent artillery, the Germans failed to breach the Entente lines. Advancing German infantry fell to rifle and machine gun fire and they suffered heavy losses.

By the end of the battle the enemy offensive had been brought to a standstill. Both sides suffered heavy losses with Germany marginally more badly hit. Casualties amongst the British Expeditionary Force effectively destroyed Britain’s highly trained pre-war professional army. Nevertheless, Ypres remained in Entente hands and the battle was celebrated as a victory in Britain.

Summary 1st Ypres:

- Result: Stalemate

- Losses for the First Battle of Ypres: Entente 125,000; German: 130,000.

- Back at home the battle was celebrated as a British victory despite some very poor strategic leadership that narrowly avoided defeat

- Alumni: No college men were lost in this battle

Second Battle of Ypres (22 April – 25 May 1915)

The battle can be best understood by subdividing it into four separate battles:

- Battle of Gravenstafel Ridge: Thursday 22 April – Friday 23 April

- Battle of St. Julien: Saturday 23 April – Tuesday 4 May

- Battle of Frezenberg: Saturday 8–Thursday 13 May

- Battle of Bellewaarde: Monday 24–Tuesday 25 May

On Thursday 22nd April 1915 at around 5pm, the Second Battle of Ypres began with the Battle of Gravenstafel in a very quiet, novel yet lethal way. Over a four-mile front the German forces deployed a weapon new to warfare: poison gas. Some 171 tonnes (volumetric equivalent 50,000 cubic metres) of chlorine was released from cylinders towards the section of the line held by French territorial and colonial troops (mainly Moroccan and Algerian).

…haggard, their overcoats thrown off or opened wide, their scarves pulled off, running like madmen, directionless, shouting for water, spitting blood, some even rolling on the ground making desperate efforts to breathe.

Colonel Henri Mordacq, quoted in Greenhalgh, E (2014). The French Army and the First World War

The effect of the new weapon was twofold. The troops in the line of the gas’s propagation, who as yet had no protection against the physiological effects, suffered significant losses. French casualties numbered between two and three thousand with one thousand to fifteen hundred of those being fatalities. Those who escaped left behind them a deserted gap in the front line through which the enemy could advance with little loss. The Germans were able to do so, prepared for any lingering pockets of gas by breathing through wads of fabric which had been soaked in sodium thiosulphate. The gas attack and subsequent engagement caused an estimated loss to allied forces of 5,000 killed and 15,000 wounded over the two days of this short battle. Illegal as it was under international treaty, through the rest of the war the technology would develop and more lethal gases would follow, resulting in over 1.3 million gas casualties, probably 20% of which were civilian.

Two days after the first release, a repeat attack was carried out near St. Julien (the Battle of St. Julien), a village lying four miles to the northeast of the centre of Ypres. The recipients of the gas were Canadian units who had been on the western edge of the first deployment. It was they who had identified the gas as chlorine. The smell of lower concentrations drifting across their territory was recognised from Canada’s chlorinated potable water system. But still there was no protection. Bert Newman of the Royal Army Medical Corps described the effects on Canadian troops:

you could see all these poor chaps laying on the Menin Road, gasping for breath… and the thing was it was no gas masks then, you see, and a lot of these chaps just had to wet their handkerchiefs and put it over their mouth or do what they could.

As an immediate response, the British began issuing cotton wool wrapped in muslin to its troops by 3 May. Physiologist John Scott Haldane developed the Black Veil Respirator. ‘Respirator’ is rather a grand name for what was simply a padded face scarf soaked in a solution of sodium hyposulphate (thiosulphate), sodium carbonate, glycerine and water. This was first issued on 20th May but at this point the Canadians had little protection. Until the deployment of protective measures, holding water or urine-soaked socks or handkerchiefs across the nose and mouth was found to be most effective, the chlorine either dissolving in the water or reacting with the ammonia in the urine.1

As with the previous gas attack, the troops fled for their lives leaving an undefended front almost one mile wide. The enemy advance was wary of lingering pockets of the heavy chlorine gas and delayed advancing. In the hiatus Canadian and British troops were able to move back into position and defend it. In one sense the Battle ended as a German failure but the casualties on the allied side were high. A further dimension to this new warfare also became evdient: undermining morale and creating fear. Private W. Hay of the Royal Scots recorded

We knew there was something was wrong. We started to march towards Ypres but we couldn’t get past on the road with refugees coming down the road. We went along the railway line to Ypres and there were people, civilians and soldiers, lying along the roadside in a terrible state. We heard them say it was gas. We didn’t know what the Hell gas was. When we got to Ypres we found a lot of Canadians lying there dead from gas the day before, poor devils, and it was quite a horrible sight for us young men. I was only twenty so it was quite traumatic and I’ve never forgotten nor ever will forget it.

The Battle of Frezenberg was a six-day action by the enemy in an attempt to take full control of the Frezenberg Ridge to the east of Ypres. After an artillery bombardment of the lower slopes of the ridge, two infantry attacks ensued but failed to take ground. A third attack was successful in pushing the defenders back, leaving a two-mile wide gap in the front line. Only an heroic night time counter-offensive by Canadian light infantry saved the situation and held the line but at the cost of 80% casualties.

The final act of Second Ypres was the Battle of Bellewaarde, played out over two days towards the end of May in the wetlands four miles east of Ypres. This was the third gas attack but intelligence led the British defenders to pass the message to all company officers to prepare:

We had only just time to get our respirators on before the gas was over us.

Captain Thomas Leahy

The subsequent attack managed to take frontline trenches on the northern flank. This was regained in a counter attack but further ground was lost in a later German push.

Summary of all Battles comprising 2nd Ypres:

- Result: German push the front between 3 and 4 miles nearer to Ypres (3 miles from the city outskirts)

- Losses for the Second Battle of Ypres: Entente 80,000; German: 35,000.

- Alumni: Harry Hotten was Killed in Action at Zonnibeke on 26th April 1915. He suffered fatal head injuries from an exploding shell, and died within a few minutes. He was buried in an unmarked grave.

Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele) (31 July – 10 November 1917)

The stragic plan of General Sir Douglas Haig, it was intended as a massive offensive to break out of the Ypres salient and capture the ring of high ground around the town before breaking out and taking the rest of Belgium and especially the coast, which was vital to the enemy U-Boat campaign. He also mistakenly thought, and not for the first time, that the German army was near collapse and that one more big push would win the war.

In my opinion the war can only be won here in Flanders

General Sir Douglas Haig, 13th August 1917

Time was of the essence in Haig’s mind. On the Eastern Front, the Russian Army had begun to collapse and be driven back. Haig anticipated a transfer of troops from Eastern to Western Front and petitioned the War Cabinet to authorise the concentration of troops and munitions to the battle in Flanders.

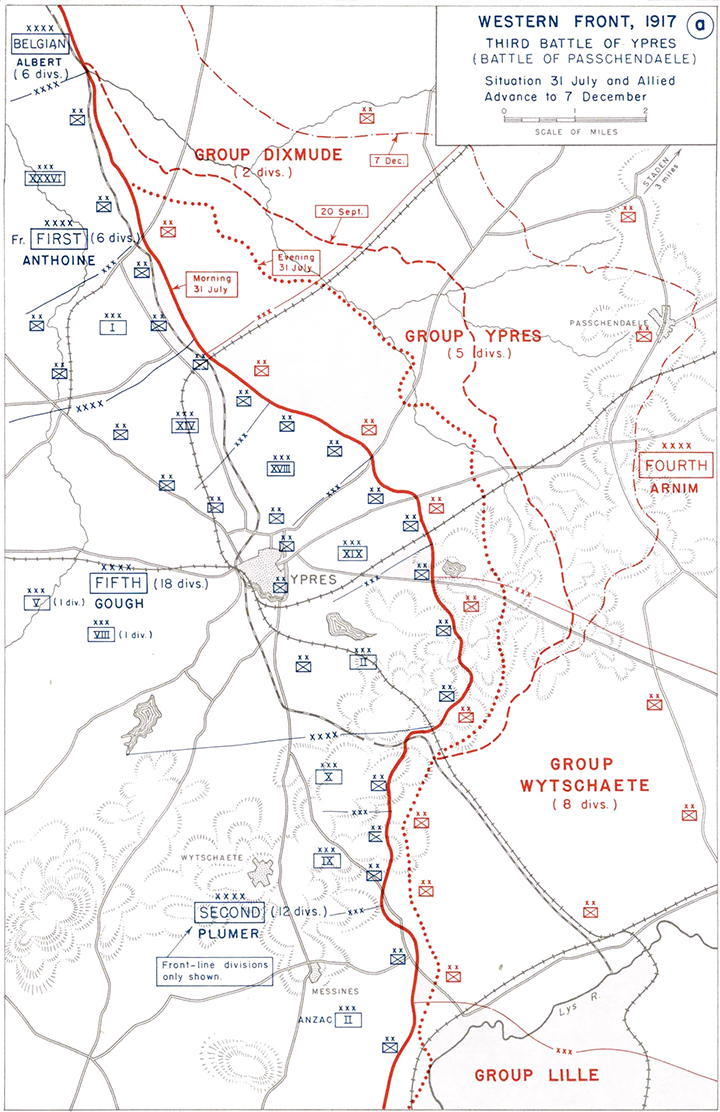

General Sir Hubert de la Poer Gough had been chosen to command the offensive and, in early June, he and the Fifth Army HQ took over the Ypres salient. The preparation for the battle began on July 18th with an artillery bombardment of enemy trenches and positions. It is estimated that 3,000 guns fired over 4¼ million shells over a two-week period. The battle proper began on July 31st 1917.

Immediately the daylight came, they had their rum ration. The Quartermaster was always good on these occasions, it was practically a double, because he’d filched or watered or done something to it to let us have some more. Anyhow, that was done. Then you gave the men your last orders. They had brief sort of ladders, two bits of wood nailed together with three or four cross pieces to form the ladder to help them get out. Five minutes before the actual time of going over, which was the worst time for the troops, that’s when their feelings might break. You’d say, ‘Five minutes to go!’ You’d shout it down the left and right of your sector. Then, ‘Four minutes… three minutes… two minutes’ and ‘half a minute!’ and then you’d say, ‘10 seconds… get ready! Over…!’

Ulrick Burke, British Officer, 31st July 1917

At dawn in the morning about, we were told, 800 guns opened up and we went over the top. It was all quite nice; we didn’t have anybody firing at us, not for the first quarter of an hour or so, anyway. We were getting along – strung out in what we called open formation, that’s a couple of yards between each man – and we came under long-distance machine-gun fire. As we were going along, the man on the left of me was hit in the arm and the man on the right of me was hit in the heart, he died – he probably died, we weren’t allowed to stop, anyway but he did, we knew he died afterwards. It missed me altogether, that was just the luck of the war.

Clifford Lane, Hertfordshire Regiment, 31st July 1917

On the first day of infantry action, French and British attacks met with moderate success in some sectors but as the day progressed the weather turned. Heavy rain impeded vision and movement as well as sapping energy and morale. Artillery was unable to range properly and therefore could not support the troops in vulnerable positions. The lack of artillery cover also made it easier for German infantry to counter-attack. The earlier gains were overturned and little had been won but at great cost. It rained constantly for three weeks. The millions of shells from only days before had destroyed the drainage canals and natural streams that had been engineered to keep the flat reclaimed marshland dry. Heavy, glutinous mud made any movement difficult: men sank to their waists. Soldiers and horses drowned in deep mud and movement of vehicles, even tanks, was almost impossible. Artillery could not be resited and aircraft were grounded due to waterlogged aerodromes and bad visibility. The offensive was halted on August 2nd to await better conditions.

It rained for three solid weeks and the plight of the men in the trenches in the northern part of Belgium was absolutely impossible. It was so impossible that the men coming out of the trenches who were wounded had to get rid of their kilts because they couldn’t walk because the pleats were covered in this horrible slime which made such a weight. I’ve never seen conditions like it; in every trench it was two feet of water!

Walter Cook, Royal Army Medical Corps

The assault was restarted at Langemarck (16th to 18th August), where the French and British took territory but once again but counter-attacks forced retreats.

I went forward and I suddenly heard a shout, ‘Get down, Sir, get down!’ and I was amongst my own men all in the shell holes. I realised we had hardly an officer left at all and they were beginning to run short of ammunition. The attack on the right had completely failed, the crucial attack of the division on the right had completely failed to make any headway. We were in a rather precarious position. The Brigadier came up and, whilst he was there, there was a sudden stampede of our men; they were driven off the hill and they fell back. We fell back and we took refuge behind an old parapet that I should think had been built in 1914. It was not thick enough, really, to be bulletproof. And there about 50 of us took refuge.

Alan Hanbury-Sparrow, commanding the 2nd Battalion, Royal Berkshire Regiment in the Battle of Langemark

Wet weather again brought further attempts to a halt. It also became clear that German morale was higher than the British generals expected. The pause was used to good effect. The leadership of the offensive changed hands when Haig gave Plumer charge of V Army as well as his own II Army.

A fresh British offensive was launched, the Battle of the Menin Road, on the 20th September under the command of Herbert Plumer which eventually resulted in some small gains being made including the capture of a nearby ridge just east of Ypres. Plumer had implemented a new ‘bite and hold’ strategy as the British tried to regain the initiative. This focused on making much more limited gains and rapid consolidation rather than the previous over-ambitious and unrealistic goals of Gough’s attacks, which had little strategic focus on resisting counter offensives. Typically a Plumer bite-and-hold attack would target a short section of the enemy front line. Before advancing, it would be heavily shelled before being assaulted in strength. The attack would halt when they reached their first objective and consolidate (‘dig in’). Another wave of attack would then leap-frog them to the next objective, which would be distance-limited. The second objective could then be taken by fresh men who had full supplies of ammunition. The first attacker could then follow up and consolidate further gains and support the new attackers. German counter-attacks would then find well organised defences occupied by prepared men rather than exhausted troops in disorganised posts. By limiting the gains made the new advanced positions would also still be in range of artillery support, pinning down enemy counter-attack forces.

The bombardment next morning when it started was the heaviest bombardment I’d ever seen in that war. I think there was a gun to every nine and a half yards of front. When the bombardment was on, there was such a din going on from the swish of the shells going over our heads and the bursting shells in front of us that we felt no fear, because we couldn’t hear the explosions of the German shells fairly near us. The 51st Highland Division took their objectives and all seemed to be going well – we had various counter-attacks which were beaten off.

Douglas Wimberley, British Officer

On the 20th September, the great attack of the Highland Division met our own regiment. It was a drumfire of several hours and this drumfire lasted on even after the Highlanders had stormed our front line and were now trying to get onwards through all these shell holes. We were started by our battalion commander and I had a platoon of grenadiers. We sprang from shell hole to shell hole. The drumfire was as heavy that I didn’t notice the singular shells. We advanced and drove the Highlanders a bit back, but we couldn’t reach the first line where our third battalion had been vanquished. They were all gone, partly dead, partly taken prisoner; we didn’t see any of them again.

Hartwig Pohlmann, German Officer

Haig then called for further pushes (early October) which were less successful. German reserve units had been brought in to shore up defensive capability. The enemy also deployed another new weapon: Mustard Gas. It was supplied to front lines only six days before the initial artillery bombardment. Used as a blister agent (vesicant) the new gas was known by them as Yellow Cross after the identifying paint markings on the shells. The British called it HS (Hun Stuff), and the French called it Yperite, after Ypres.

Never a General to be deterred by losses, Haig ordered three further attacks by the exhausted men on the Passchendaele ridge in late October.

It was a dreadful experience. The weather was continuously bad for weeks before that action. I think I very nearly lost my job as a battalion commander because I sent in a written protest to the brigade that we couldn’t be successful. I was very severely told off for that. I don’t think our leading troops got more than 50 yards. We simply stuck in the mud. Anybody carrying a Lewis gun or any heavy weight like that simply couldn’t get on, it was beyond his strength. I spent that night in a horrible shell hole with my orderlies, one of whom was killed sitting on the top of the shell hole. But there was never any chance of success and this I had reported to the brigade as my considered opinion and endless lives were lost that night just for nothing at all. But we ought not to have been allowed to go at all.

Alfred Irwin, British Officer, 12th October

We were going to do one of these attacks at Passchendaele and we had to attack a line of German blockhouses which were situated around Passchendaele in seas of mud. Well, this boy had just joined the company, he was younger than me. He suddenly collapsed and said that he couldn’t go on. So I said sternly to him, ‘You get up and go on, if you go on, you may well not be shot, but if you lie here or go back, you’ll be shot for a certainty!’ I remember the words I used to him! He pulled himself together, and he got through. The attack, like frankly the whole of the Battle of Passchendaele, was a failure.

Graham Greenwell, 26th October

The casualties in these final actions were horrific. British and Canadian forces fought their way through to the by now obliterated village of Passchendaele on 6th November 1917, with Canadian forces in particular exhibiting tremendous courage and sustaining huge losses (around 16,000). The fall of Passchendaele marked the culmination of Haig’s offensive, which he thought a success.

Summary of all Battles comprising 3rd Ypres/Passchendaele:

- Result: Entente forces move the front between 4 and 5 miles and gain some of the high ground around Ypres

- Losses for the Third Battle of Ypres (figures are disputed, hence the wide ranges): Entente 240,000–448,614; German: 217,000–400,000.

- Alumni:

- William Herbert Carr was killed in action near St. Julien on the 20th September 1917

- Frederick William Randolph died of wounds received at Shrewsbury Forest (3.5 miles ESE of Ypres) on 29th September 1917

- George William Stockwell was killed in action at Gloster Farm, Poelcappelle on 6th October 1917

- Ernest John Harland was killed in action at Reutel (near Becelaere) on 9th October 1917

Subsequent Actions

Fourth Battle of Ypres (7 – 29 April 1918)

Usually called the Battles of the Lys this comprised the following separate Actions:

- Battle of Estaires (9–11 April)

- Battle of Messines (10–11 April)

- Retirement from Passchendaele Ridge (11-16 April)

- Battle of Hazebrouck (12–15 April)

- Battle of Bailleul (13–15 April)

- Battle of Merckem (17 April)

- First Battle of Kemmel (17–19 April)

- Battle of Béthune (18 April)

- Second Battle of Kemmel (25–26 April)

- Battle of the Scherpenberg (29 April)

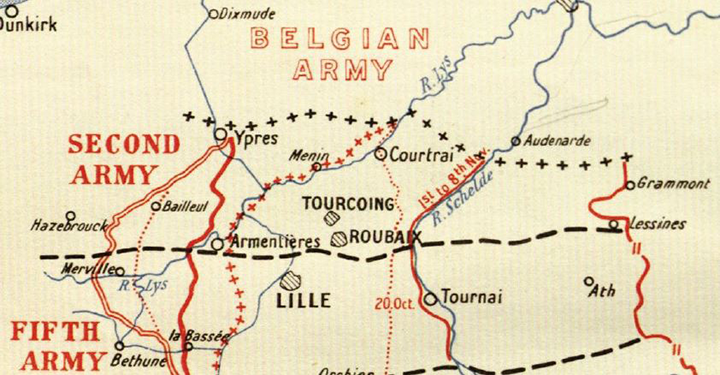

All of these battles and therefore the Fourth Battle of Ypres was a rearguard action in response to the German Spring Offensive of 1918. The object of the enemy was to capture Ypres in a lightning sweep using specially trained and equipped Stoßtruppen—stormtroopers—and drive through to the coast. This would cut the remaining Flanders Entente armies off from their supply lines which came from the Channel ports further southwest. Called Operation Georgette, it was similar to the better-known Operation Michael which had begun earlier. Both were part of the Spring Offensive.

Fought by the German Sixth Army, the attacking front ran from NNE to SSW, roughly parallel to the line of the River Lys. Many of the defending troops were exhausted or were suffering low morale. Germans successes were considerable in the early phases: Allied lines were overrun and penetrated to a depth of over nine miles. However, through rearguard actions and in influx of French infantry, the strike ground to a halt and failed to capture Hazebrouck or force a British withdrawal from the Ypres salient. The Stoßtruppen suffered heavy casualties and, by 29 April, the offensive was called off.

Summary of 4th Ypres:

- Much ground lost but German forces expended

- Losses: Entente 120,000; German between 86,000 and 110,000

- Alumni:

- Sydney Robert Slidel was wounded at the Battle of Baillieul on 15th April and died of wounds at on 20th April 1918

- Joseph Martin Sharp was wounded at Calonne on 25th April and died of wounds on 29th April 1918

Fifth Battle of Ypres (28 September – 2 October 1918)

Also known as Advance of Flanders and Battle of the Peak of Flanders.

Following the failure of Operation Georgette (see above), German forces were exhausted, short-supplied and morale was low. Allied forces, although equally battle-weary were rested by September 5th and seeing numbers increase with American soldiers augmenting front line Battalions. This enabled Foch to plan what was to become known as the Grand Offensive. Rather than focus on small, localised strikes against limited sections of enemy front line trenches he proposed hitting as wide a front as possible. The Entente forces in the Ypres Salient provide a northern pincer offensive towards Liège while further south the Fifth Army were to press eastward. On 28th September more ground was gained in one day than in the entire Passchendaele offensive of 1917. All the losses of the spring were regained and the battle was the beginning of the eastward push that would culminate in the Armistice of 11th November.

Summary of all 5th Ypres

- Losses of the Spring Offensive made good. The beginning of the end of the war

- Losses: Around 9,000 Allied casualties; German casualties unknown, PoWs 10,000

- Alumni: None

Other Losses

The above brief outlines do not cover the entirety of the conflict in Ypres/Flanders region. The ‘lulls’ between the battles were often anything but peaceful and simply holding the line on a day-in, day-out basis was costly in men and equipment. Beligerence did not stop with the end of a battle: the small arms fire of rifleman and sniper, the rattle of machine guns, bombing from aircraft and the activity of heavy ordnance were ever-present. There were small-scale attacks, working parties and reconnaissance details in no-man’s land, troop movements on exposed roads and sections of trenches, etc.. All of these were daily hazards of Army life. As mentioned at the outset, a further four Wintonians lost their lives in these times.

- Alumni who Died Outside the Major Battles

- George Samuel Hewitt was killed in action near the Messines-Wytschaete Ridge on 30th May 1917

- Henry Stanley Gwynne was killed in action at Moated Grange, near Hellfire Corner on 24th November 1917

- Percival Samuel Henry Grice was killed in action at Wulverghem on 2nd September 1918

- Merton Alfred Rose was wounded at Bac St Maur on 6th September and died of wounds on 19th September 1918

Nothing that has been written is more than the pale image of the abomination of those battlefields, and… no pen or brush has yet achieved the picture of that Armageddon in which so many perished.

Philip Gibbs, English journalist who served as one of five official British reporters in the War

Researcher and Author: John Vickers

Sources

Battle of passchendaele (2023) Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/

wiki/Battle_of_Passchendaele (Accessed: 04 November 2023).

Battle of the Lys (1918) (2023) Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/

wiki/Battle_of_the_Lys_(1918) (Accessed: 04 November 2023).

Fifth battle of ypres (2023) Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/

wiki/Fifth_Battle_of_Ypres (Accessed: 04 November 2023).

The final advance in Flanders (2015) The Long, Long Trail. Available at: https://www.longlongtrail.co.uk/

battles/battles-of-the-western-

front-in-france-and-flanders/the-

final-advance-in-flanders/ (Accessed: 04 November 2023).

First Battle of passchendaele (2023) Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/

wiki/First_Battle_of_Passchendaele (Accessed: 04 November 2023).

IWM collections (no date) Imperial War Museums. Available at: https://www.iwm.org.uk/

collections (Accessed: 04 November 2023).

Macdonald, L. (1996) They called it Passchendaele. London: Penguin.

Map images (no date) British First World War Trench Maps, 1915-1918 – National Library of Scotland. Available at: https://maps.nls.uk/ww1/

trenches/index.html (Accessed: 04 November 2023).

The National Archives (2009) The Discovery Service, Search results: service records | The National Archives. Available at: https://discovery.nationalarchives.

gov.uk/results/r/?_q=service+

records&_sd=1914&_ed=1920&

_hb=tna&_d=WO (Accessed: 04 November 2023).

Second battle of passchendaele (2023) Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/

wiki/Second_Battle_of_Passchendaele (Accessed: 04 November 2023).

Snelling, S. (2012) Passchendaele 1917. Stroud: History.

Warner, P. (1988) Passchendaele: The story behind the tragic victory of 1917, (by) Philip Warner.