Major Ralph Smith

26th July 1892”19th July, 1916

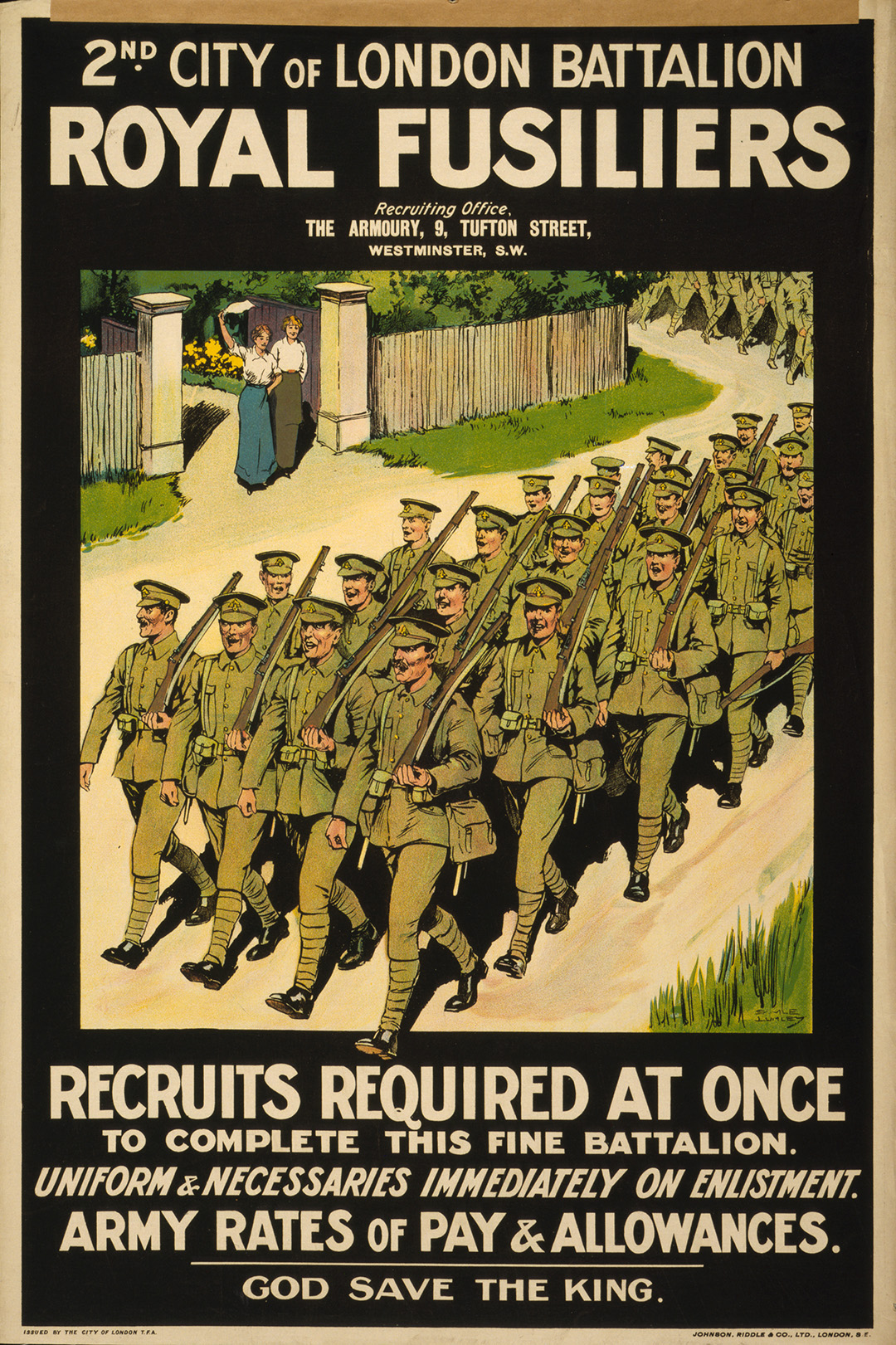

Private Major1 Ralph Smith, 3243, of the London Regiment, 2nd (City of London) Battalion, London Regiment (Royal Fusiliers), died of wounds on 19th July, 1916 in France.

Major’s Family

A Snapshot of English Social History

In the mid-1820s, Major’s paternal grandfather and grandmother Smith, Ezekiel and Sarah (née Priest), were born and bred in the Black Country”the area to the west of Birmingham, so-called because of its underlying 30-foot coal seam. Their lives began and revolved around the settlements of Halesowen, Dudley and Rowley Regis; all lie within its ill-defined borders, in the County of Worcestershire. Of these settlements, Rowley Regis features most prominently in the family record.

Rowley Regis parish is one of the most populous of the manufacturing districts of Staffordshire, the inhabitants being principally employed in mining and the making of nails, anchors, chains and rivets; the potteries of Messrs. Doulton and Co. and Messrs. Hingley’s iron works and collieries are of considerable extent.’ 2

Ezekiel and Sarah were employed in typical Black Country industries: Ezekiel was a rivet-maker and Sarah worked, along with all members of her family who were 14 and older, as a nail-maker.3 Sarah continued this work after marriage.

There is a symmetry in both sides of this generation of the family. All of Major’s four grandparents carry the name Smith. This unusual situation arose because his father (also called Major Smith) married Ellen Smith. If that weren’t sufficient confusion, his maternal grandfather, Thomas, was also a Black Country nail-maker. His wife brought some variety to the family line as she was a chain-maker, though brought up in a household of nail-makers.

All of these trades left families in grinding poverty, often little more than slaves to the supplier of raw materials and buyer of finished products”more often than not these were one and the same person, called a nailmaster. In the late 19th Century, 50,000 Black Country nail-makers were controlled by 50 nailmasters who could dictate rates of pay, hours of work, and who often owned the houses that workers lived and the tools they worked with and rented from them. None of the grandparents was able to escape this indentured servitude; they were born, lived and died in their trade.

The pattern seemed set to continue. Major’s father was born in Rowley Regis in 1862 and, in 1881, is recorded as a nail-maker. On 5th August, 1889 he married nail-maker Ellen Smith, again of Rowley Regis. Ellen was five years younger than he, and in just over a year, their first child was born in Halesowen: Florence.

By the 1891 Census, his trade had changed to Bedstead [uncertain word] Maker’. This industry, a major employer in the area at this time, was in steep decline.4 As in the nail trade, pay rates were very low. There was unrest in the workforce and it is possible that his father was involved in the successful bedstead-makers strike of December 1889, seeking better wages. Into this economically struggling family Major Ralph was born on 26th July, 1892, followed by Winifred May (1896) and Gladys Ellen (1898).

The escape from the Black Country and its associated industrial drudgery lay in an unusual direction: Major Ralph’s father became a Congregational Evangelist.5,6 The family must have moved with his new calling, first of all to Godalming, Surrey, where Major, Winifred and Gladys were born. The new life still had familiar challenges; the job brought with it a meagre salary of £90 per year, most of which was used to pay for their family home.‘ 7

By 1901, (it is in this census we read of the change to Congregational Evangelist) the family are to be found in East Boldre, Hampshire. Set on the edge of the New Forest between Lymington and Beaulieu, this rural village was a far cry from their old haunts.

The move would have disrupted the older children’s schooling. There is some uncertainty over where the children were educated. The natural choice would be the village National School.8 However, Major’s later college Student Record cites South Baddesley National School as his elementary school, which was over 3 miles distant. However, as this form often skips very early schools, it could be that he attended first East Boldre and then South Baddesley. He then attended what is given simply as Medstead’. This indicates another family move to northeast Hampshire and schooling in Medstead National School”a small village school of around 60 pupils under the master, James H. May.

Major had obviously done well at school because he was able to secure a position as a pupil teacher. We return to Gallagher, who draws from post-War correspondence and insurance claims on behalf of Surrey County Council Education Department employees who had been killed in action during the Great War:

his parents invested a great deal in Major’s future, sacrificing much at their own expense to ensure he would receive the best education possible and ultimately become a schoolmaster. Major spent three years as a pupil-teacher’ 9

Usually a pupil teacher post would be in an elementary school”often the pupil’s existing school”but Major found a position at nearby Alton Grammar School. This is most unusual and would have been very different in ethos and educational standards.

At the end of his time as a pupil-teacher, in 1910 Major Ralph secured a place at Winchester Training College. The teacher-training he would receive there would, after two further years working as an assistant-teacher, give him Certification status. The fees involved would have been a further drain on the family purse.

Training at Winchester Training College

1910“1912

College Chapel

Nonconformist students, such as Major, were at a disadvantage at the College, which had a strong Church of England foundation. They would find it difficult to reach the required standard in Religious Education, which was heavily Anglican-centred. This was also a problem for those who had been brought up in unchurched families and educated in Board Schools, where they would not have received much religious education:

William Smoker, who entered college in 1902 at the age of 21, had taught for nearly five years as a pupil-teacher in an East London dockland area school. He spent half of each day at the school and the other half at the Woolwich Pupil Teacher Centre. His religious education had, however, not received the same attention as those pupil-teachers serving in Church schools, and on entering college he encountered some difficulties. Recollecting some of these difficulties in 1966 he wrote:

The Prinny 10 was most assiduous to us in his twice a week Divinity lectures. I had not been apprenticed in a Church of England School, and although I never appeared before the Principal for a breach of College rules, I was interviewed by him twice for my failing in Prayer Book history and for my inability to answer such Catechism questions as, ‘What did your Godfathers and Godmothers then for you?’ 1112

It is likely, however, that Major’s background as a child of the manse, and his education in a string of National Society schools (which had at its heart the education of children according to the Principles of the Established Church in England and Wales‘) would probably have given him the tools needed to navigate his way through the Divinity part of the curriculum.

College life was busy: lectures, practical teaching training, Chapel attendance and personal study filled most of the students’ time, but there was a recreational side of college life. Debates, indoor and outdoor games and sports, concerts, social events and other activities played a large part in the cohesion of the student body. Students printed an internal publication of news and events, The Wintonian. In this we read the only reference to him: In the Dormitory Cup competition, Major Smith dressed up as a Red Cross Ambulance man.’

The financing of Major’s time at College must have been difficult. There were fees to find and a list of items he had to buy and take with him at the start of his studies. Later Surrey County Council Education Department files report: During this time, he relied on his parents’ financial support, as well as the small amount he had earned being a pupil teacher.’ 13

Major’s Student Record places him at 17th out of his year of 34 students, with a 61.4% average. His strongest subject was music and he finished his course towards the higher end of the Class II group (ranged from Class I to Class III).

At the successful conclusion of his studies in 1912, the College records show that Major left to teach at Ludlow Road Boys School, Itchen, Southampton. In order to achieve Certification, the leaving student had to complete two years teaching at the same school. Although we have no direct proof of dates, we must assume that Major completed two years in Itchen and then moved school since he is listed as teaching at Lingfield Council School in Surrey when he enlisted for wartime Army service.14

He showed his gratitude for the family’s support throughout his training: when he became a qualified teacher, Major did what he could in return for his parents, becoming a great financial help to his family by sending money home almost every month. Even after joining the army, Smith gave permission for his parents to use his money as sent by the Lingfield School of Managers. Whilst they did use some of his wages, Major’s parents also saved some money in the bank, in the hope of his return.’ 15

We do not know the exact date of his enlistment into the Army, but his War Gratuity payment, which was based on length of service at the time of death, would place this in November 1914, shortly after he started his in his new post at Lingfield.

Life in Khaki

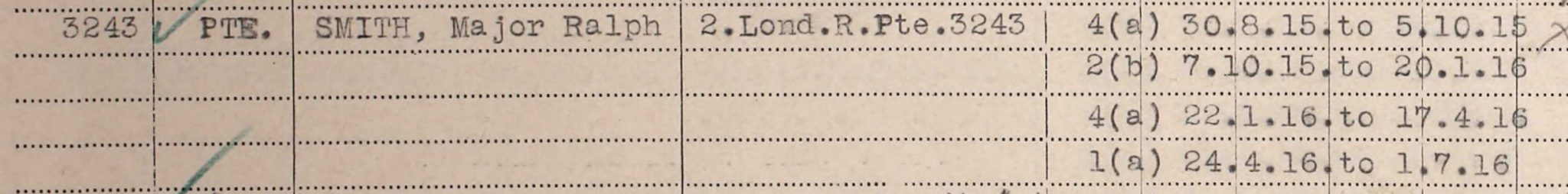

Major joined the 2nd Battalion London Regiment (Royal Fusiliers), enlisting in London. His movements throughout the War are listed on his Medal Roll, where the Theatre of War is given by code, and the dates for disembarkation at and evacuation from that particular Theatre:

Key to the Army Theatre Codes:

4a African Theatre: British East Africa, German East Africa, Rhodesia, Nyasaland and Uganda

2b Balkan Theatre: Gallipoli and Aegean Islands

4a Egypt 16

1a France and Belgium

These places and dates tell us that he was in the 2/2nd Battalion. His first period marked as 4(a) was simply time spent in Egypt at a transfer station, awaiting onward transport. The second period is of particular importance, between October 1915 and January 1916, when the Battalion was engaged in the Gallipoli debacle. Major and his men landed on 7th October and met up with others in the Battalion, who had been in Gallipoli for some time, on the 10th. At this point in the campaign disease was the biggest enemy. During the week when Major’s recruits joined their fellows, one man had been killed, seven wounded, but thirty-four lost to active service through illness. The War Diary records that, on arrival, the new men were only wearing thin Khaki’”unsuitable for the cold, wet weather and supplied probably as a result from being shipped there from Egypt. Within days, the Diary reported, A very cold day. Freezing hard and a bitter wind.’ Many would die of exposure as well as enteric diseases.

As with most men in that invasion, the 2nd Battalion also suffered terribly from the firepower of the enemy. The hell of Gallipoli came to an end in January 1916: Major and his Battalion joined transports, returning them to Egypt as part of the general ignominious withdrawal and the end of the campaign. They would be stationed there, re-equipping and awaiting orders until 17th April, 1916, when the embarked for the Western Front.

The Battalion arrived in Marseilles one week later and were then moved to Rouen. They were to be stationed there until June when they were disbanded. Major was transferred to another Battalion of the London Regiment, the 1/12th.

The Battalion Diary indicates that Major and his new comrades were in the Wulverghem / Messines / Wytschaete sector, holding the line. In typical fashion, they were in trenches for a few days at a time then relieved by another Battalion. They would then regroup, train and parade in billets behind the lines, before moving up once more to relieve others.

We do not know when Major was wounded, but it was a few days before his death.17 It may be helpful to give an example of one day’s typical War Diary from just from around that time:

Le Tréport Hospital complex. The huts are of the No.2 Canadian Hospital. Identical huts further to the left housed No.16 General Hospital. In the background can be seen the Trianon Hotel, which housed the No.3 British General Hospital. It stands above the sea cliffs just south of Tréport, 15 miles northeast of Dieppe.

Major was evacuated from the front line, to the hospital at No.16 General Hospital at Le Treport. The following is a letter to his parents from an Army Chaplain:

No.16 General Hospital

B.E.F.

France

July 20th, 1916

Dear Sir,

I understand that you are the father of 0/3243 Rfm. M.R. Smith who died in hospital here yesterday morning at 1 a.m. I saw a good deal of him the days previous to his death. He had been getting on well, and we all hoped that he would recover. His death has been a real sorrow to all of us and I write to you to offer you my deepest sympathy.

I soon discovered that your son was a man above the average and we had many quiet talks together about school-teaching, education, religion, and so-forth. Rfm Smith enjoyed reading, and just before his death he asked me for some writing paper so doubtless you heard from him. On the night of the 18th it was obvious that he was sinking, and although breathing was difficult he was not suffering much. He asked me to read to him, and I read some verses of Scripture”Psalm 23, Isaiah 43 v.1 & 2, Romans 8 v.3-39. I then prayed with him and at the close he said Amen.

I am sure that in the midst of your sorrow you will have a just pride in your son’s devotion and self-sacrifice. I can well understand how grievous his loss must be to you all, because although I had known him only a short time I had grown very fond of him. Everybody was impressed by his quiet, brave, spirit, his gentleness and thoughtfulness.

Yours with deep sympathy,

(Signed) Hubert L. Simpson

Chaplain to the Forces

P.S. I buried the body in the British Cemetery (Mont Huon) here (Le Treport). A wooden cross will be erected over the grave bearing his name, regiment, and date of death.

Major is buried in the British cemetery of Mount Huon in Le Tréport, France.

His sister Gladys followed Major into teaching. This was something which had pleased him and he expressed a desire to support her financially. Although his official will left all property, effects and money to his father, some of the money which had been saved in the bank was used to support his sister through her education and training to teach, at Goldsmith’s College.

Major and Ellen Smith wrote that they had no regrets about the expenses or sacrifices’ for their son: he was worthy of it’.20

Researcher and Author: John Vickers

Footnotes

[1] Major is his first name, not Army rank

[2] Kelly’s Directory of Staffordshire 1896, p.294

[3] Often appearing in records as Nailer’ or Nailor’

[4] T. H. Kelly, ‘Wages and labour organisation in the brass trades of Birmingham and District’ (Ph.D. thesis, Birmingham University, 1930).

[5] The Congregational churches were a loose association of independent chapels and not a structured denomination. Each congregation/chapel was autonomous. The local church would appoint a minister directly and agree employment terms and conditions (including, in this case, his title of Evangelist rather than the usual Pastor or Minister). In 1972 many of the Congregational churches joined with the Presbyterian Denomination to form the United Reformed Church

[6] There is no prior intimation that the family had nonconformist connections, but this would not have been unlikely. Nonconformist churches were particularly active and successful in areas of social deprivation and amongst the industrial working class. Their work was at its zenith in the late 19th Century.

[7] Kathleen Gallagher research article at http://www.surreyinthegreatwar.org.uk/story/major-ralph-smith/ The article is the result of an investigation of documents held by Surrey History Centre. The file (SHC ref. CC7/4/4, nos. 1-50) contains correspondence and insurance claims on behalf of Surrey County Council Education Department employees who had been killed in action during the Great War. The cases date from 1915 to 1918. Major Ralph Smith’s documents are in File 15 of the set.

[8] A small school of 60 or so pupils, under the headship of Thomas Lambert. (Kelly’s Directory of Hampshire and the Isle of Wight, 1898)

[9] Gallagher

[10] The Principal was Henry Martin (b. 1844, d. 1919) Principal 1878-1912, he was a member of the Alpine Club and one of a few to have reached the summit of the Matterhorn.

[11] Today this third question of the Shorter Catechism reads as a misprint. It is a grammatically correct but archaic form of What then did your Godfathers and Godmothers do for you?’

[12] A History of King Alfred’s College, Winchester 1840-1980 by Martial Rose

[13] Gallagher

[14] National Union of Teachers War Record 1914“1919

[15] Gallagher

[16] This second occurrence of 4a carries a different definition from the first as the Codes were changed on 1st January, 1916

[17] Gallagher

[18] Parados: The earth mound behind the trench protecting troops, particularly those on the fire-step, from shrapnel, blast, and the possibility of enemy fire from the rear.

[19] O.R.: Other Ranks, i.e. Privates and non-Commissioned Officers.

[20] Gallagher

[21] Ibid.

Sources

Ancestry (2018). Home page. [online] Available at: www.ancestry.co.uk [Accessed 2018].

Commonwealth War Graves Commission, (2018). Mount Huon Military Cememtery, Le Treport. [online] Available at https://www.cwgc.org/find-a-cemetery/cemetery/11700/mont-huon-military-cemetery,-le-treport/ [Accessed 2018].

Kelly’s Directory (1896). Kelly’s Directory of Staffordshire 1896. [online] Available at: http://specialcollections.le.ac.uk/cdm/ref/collection/p16445coll4/id/339984 [Accessed 2018].

Kelly’s Directory (1898). Kelly’s Directory of Hampshire and the Isle of Wight, 1898. [online] Available at: http://specialcollections.le.ac.uk/cdm/ref/collection/p16445coll4/id/218262 [Accessed 2018].

The Long Long Trail, (2018). Medal roll theatre codes. [online] Available at: http://www.longlongtrail.co.uk/soldiers/how-to-research-a-soldier/campaign-medal-records/how-to-interpret-a-campaign-medal-index-card/medal-roll-theatre-codes/ [Accessed 2018].

National Union of Teachers. (1920). War Record 1914“1919. A Short Account of Duty and Work Accomplished During the War. London: NUT.

Rose, M. (1981). A history of King Alfred’s College, Winchester 1840-1980. London: Phillimore.

Surrey in the Great War (2018) Major Ralph Smith – Case 15. [online] Available at: http://www.surreyinthegrhttp://www.surreyinthegreatwar.org.uk/story/major-ralph-smith/eatwar.org.uk/people/page/10/?s=ham&search=1 [Accessed 2018].

Surrey in the Great War (2018) Major Ralph Smith – Outline. [online] Available at: https://www.surreyinthegreatwar.org.uk/person/97255 [Accessed 2018]. [Accessed 2018].

Vickers, J. University of Winchester Chapel Memorial Rail image.

| University of Winchester Archive “ Hampshire Record Office | ||

| Reference code | Record | |

| 47M91W/ | P2/4 | The Wintonian 1899-1900 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/5 | The Wintonian 1901-1902 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/6 | The Wintonian 1903-1904 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/7 | The Wintonian 1904-1906 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/8 | The Wintonian 1905-1907 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/10 | The Wintonian 1908-1910 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/11 | The Wintonian 1910-1914 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/12 | The Wintonian 1920-1925 |

| 47M91W/ | D1/2 | The Student Register |

| 47M91W/ | S5//5/10 | Photograph of 5 alumni in Mesopotamia |

| 47M91W/ | Q3/6 | A Khaki Diary |

| 47M91W/ | B1/2 | Reports of Training College 1913-1914 |

| 47M91W/ | Q1/5 | Report and Balance Sheets 1904- 1949 |

| 47M91W/ | R2/5 | History of the Volunteers Company 1910 |

| 47M91W/ | L1/2 | College Rules 1920 |

| Hampshire Record Office archive | ||

| 71M88W/6 | List of Prisoners at Kut | |

| 55M81W/PJ1 | Managers’ Minute Book 1876-1903 | |

| All material referenced as 47M91W/ is the copyright of The University of Winchester. Permission to reproduce photographs and other material for this narrative has been agreed by the University and Hampshire Record Office. | ||