Early Life

It is unsurprising to find Albert amongst the ranks of the teaching profession as his father William was a schoolmaster, rising from the background of a labouring family into the profession by the age of 18.

William’s roots lay in Poplar, London. He was born in 1843 to a sawyer but by the age of 18 appears in records as one of five teachers employed at the Asylum for Idiots’, situated on Earlswood Common between Reigate and Redhill, Surrey.

The asylum was an innovative and pioneering work in understanding the difference between, in today’s terms, special needs education and psychiatric care. Its work, focused solely on the former, was in many ways the forerunner of special needs education today. It is worthy of inclusion in Albert’s story, as his father’s experiences there would no doubt inform his thinking and his approach to teaching.

Until the institution’s foundation in 1855, the plight of the idiot had been bound up with the lunatic. An independent church minister, Dr. Andrew Reed D.D. (1787–1862), had visited institutions for the care of idiots in France, Switzerland and Denmark, and had corresponded with specialists in Paris and Berlin (Drs Itard, Seguin and Saegert). He became convinced that special and individual attention would help the idiot develop as far as was possible and to this end founded the asylum.

The aim of the institution was ‘not merely to take the Idiot and Imbecile under its care, but especially, by the skilful and earnest application of the best means in his education, to prepare him, as far as possible, for the duties and enjoyments of life’. Preference was given to young children, who it was felt, would benefit most from the education given at the institution.

William’s work there, at the age of 18, would have been as an unqualified assistant teacher—though whether the staff of such an institution fitted the general job titles found in mainstream education is not known. It must be assumed that he then went to training college as he next appears as a schoolmaster in Bournemouth in 1871. He was to meet and marry Jane Oatley (b.1848, Bath, Somerset) there in 1874. She was a schoolmistress teaching in a National school in Holdenhurst. Now on the northeast outskirts of the conurbation, the parish of Holdenhurst and Throop was then deeply rural, with the National school mid-way between the two hamlets, overlooking the River Stour. As William appears at that school as schoolmaster in the census following their wedding it is reasonable to assume that it was there they met.

The couple settled in Holy Trinity School House where William continued as schoolmaster. Jane soon had her hands full. By 1881 she was mother to five children aged from 1 month to five years old and, ten years later the brood had grown to nine, aged one to fifteen. A tenth child, Edwin, had died shortly after birth. Life must have been crowded in the school house which was not large. Albert was their sixth child, born on October 2nd 1882. The children, with their later occupations are as follows:

Francis William (1875-1941, Gardener)

Percy Ernest (1876-1953, Bank Clerk)

Walter Alfred (1878-1946, emigrated to New York)

Susan Blanche (1879-1941, Teacher)

Edith Harriet (1881-1931, Wool Store Assistant, later her father’s carer)

Albert Edward (1882-1915, Teacher)

Ethel Jane (1884-1956, Teacher)

Harold George (1886-1954, Naval Sick Berth Chief Petty Officer, later Pathology Technician)

Edwin Arthur (1887-1888)

Cecil Henry (1889-1964, Metal Turner)

All were born while William and Jane were at Holdenhurst, with the exception of Susan Blanche (always known as Blanche) who was born in Bath where Jane herself was born. It must be assumed that Jane had travelled back to her family there for the confinement.

The family had moved from Holdenhurst by 1898: the school head is recorded as Miss Duthy and William is to be found listed in the Bournemouth Directory as Master of Holy Trinity School, St. Paul’s Road: ’built, with master’s residence, in 1850, & enlarged in 1874, for 500 children; average attendance 476; William Beaumont, master; Miss Jennie Cooper, mistress; Miss J Bruce, infants’ mistress’. The census of 1901 tells us that four children are still living at home in the school house of which and Albert and Ethel are pupil-teachers. William and Jane also had a live-in servant, a local girl called Beatrice Pope, aged 18.

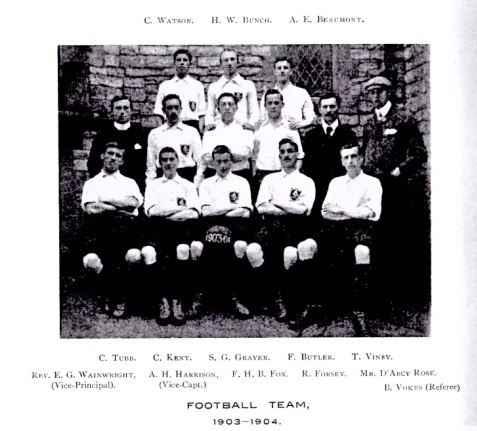

Albert attended the Bournemouth and District Pupil Teachers’ Centre from 1899 to 1901 for study and training on day-release and Saturday mornings. He was one of 72 pupil-teachers1 working towards their King’s Scholarship Examination—the entry requirement for teacher training college. The centre also had 12 students (probably working as assistant teachers) who were studying for their teacher’s certificate; providing they were recommended by a school inspector this would allow them to train at college on a fast-track one-year course. Albert is listed amongst the centre’s prize-winners, gaining a fourth-place prize in his second year there. 2

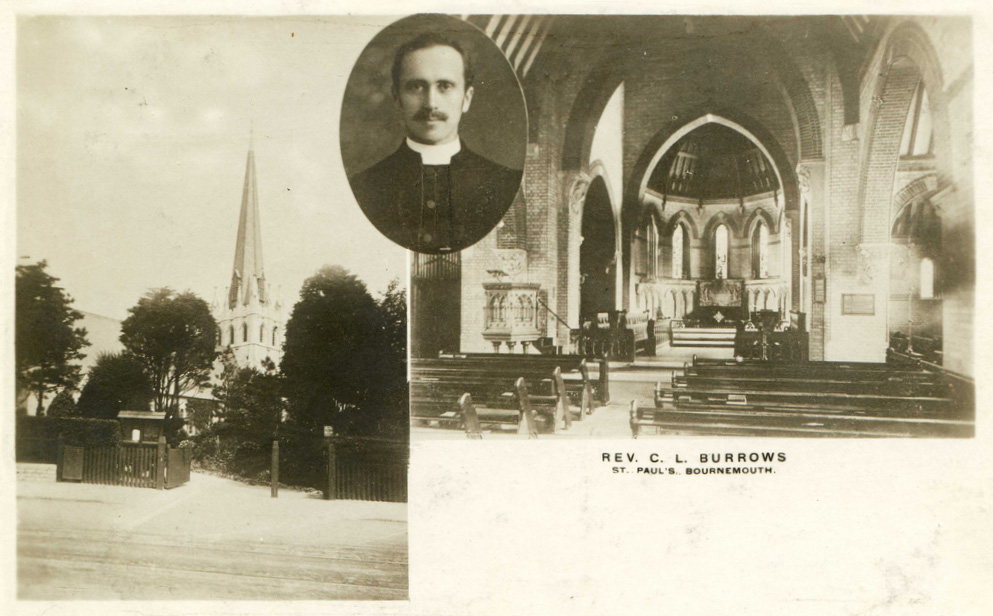

A postcard of St. Paul’s Church, Bournemouth from the turn of the century. The Rev. Burrows was well known to the family and presented Albert with his leaving present. Image reproduced under Creative Commons Licence.

During this time of study, he was working as a pupil-teacher at Central School, Bournemouth.3 Central School is synonymous with Holy Trinity School as William is named as head of both schools in the same period. To add further to the confusion, the school was next to St. Paul’s parish church in St. Paul’s Road and is also referred to as St. Paul’s School. His father was a leading light in the teaching profession in the Bournemouth area, heavily involved in the teacher’s association and the National Union of Teachers. His name appears frequently in the press in connection with these. Being a pupil-teacher under a father’s gaze is an experience shared by a few of the fallen.

For Albert, the time had come for him to spread his wings:

‘A very interesting presentation took place yesterday in the above schools, when the Rev. Canon Eliot presented Mr A.E. Beaumont, son of the headmaster, with a handsome travelling trunk and set of brushes, on his leaving for Winchester Training College, he having obtained a King’s Scholarship there. The Rev C.S.4 Burrows also presented a very handsome book, entitled Palestine Illustrated. Mr A.E. Beaumont suitably replied.’5

Winchester Training College

Albert would have taken his King’s Scholarship entrance exam in December 1901 at the college. Alongside him in the examination hall would have been William Smoker A.R.P.S., who wrote of his college experiences during December 1966 at the age of 86:6

My connection with the College began on Monday 9th December, 1901. There, to take the first King’s Scholarship Exam. Edward VII was King then, for Queen Victoria had died on January 22 at 6.30 p.m., in 1901

In my journey through London to Waterloo Station when bound for Winchester, I bought a watch for 6/6d. the better able to gauge my time in answering papers. The fare from Waterloo to Winchester, return, was 10/6d., the distance 63 miles and the time of journey 75 minutes.

The exam lasted from Tuesday to a late Friday. Two Senior Prefects directed us and the College asked a modest 15/– only, for our board and bed. About 50 of us sat, I was one of the successful, being 9th on the list. I remember two details of that week: one was the question:— draw the position of a sheet of metal weighing one pound and suspended from one corner, when a 2lb. weight is attached to an adjacent corner, and the other was an evening chat I had with the kindly vigilating H.M.I., when we discussed why so many cities like Winchester grew up in such damp and waterlogged hollows.

He arrived at the time of Leggett and Smoker, students whose memoirs of the time feature prominently in later histories of the college. Both stressed the importance of gaining the training before entering the college as this so often gave them an advantage over the post graduates who completed theirs after gaining their degrees.

from the Wintonian Magazine

‘Amenities of college life: from the present-day standpoint these were perhaps few. There was no heating at all of corridors or dormitories, and one open fire only in each of the Lecture Rooms, the Dining Hall, and the Staff studies, with slow combustion stoves in the Library, Common Room, etc.. There was one tap only to the wash basins in the cubicles not a hot one! We washed and shaved with cold water as a rule, for quite a walk and waiting in the queue was involved for most of us to get hot water from the single tap in the Blax dormitory. We might on some other occasions venture to knock on the door leading into the kitchen and make an appeal. On one afternoon in the week we could take our turn in one of the bath-cubicles. Sick-bay? Well, there was one hidden away at the furthest end of the Blax. Most of us saw it but once and did not invite a closer acquaintance.

But let it not be imagined that we dwelt upon this lack of amenities. Far from it the finest assets of Coll were its situation, its abundance of fresh air, and the fact that we were all in the swim together. We sometimes grumbled, but we were seldom out of sorts and on the whole life at Winton was grand.’

Into the World and War

Then he went abroad, first to Germany as a teacher of English, and for the last three years he was at Ghent in one of the Secondary Schools.

This shorthand account omits that his first port of call in continental Europe was Paris, where he gained diplomas as a linguistics student,8 enabling his subsequent language teaching. Again, from his father’s letter: ‘He was most proficient in several European languages (French, German, Flemish, Dutch, etc.)’. Also, while teaching in Germany he acted as a guide for a visiting Bournemouth football team.9

At the outbreak of war, Albert was working in Belgium. The pre-war German strategy (the Schlieffen Plan) was to avoid the strongly defended France-German border and invade France through Belgium-Luxembourg-Netherlands, then sweeping south into France. On July 24th, the Belgian government had announced that, in the event of war, Belgium would continue its historic stance of neutrality. On August 2nd a German ultimatum was communicated to King Albert and the Belgian government, demanding passage through Belgium. This was refused, and Britain guaranteed military support to Belgium. Germany declared war on Belgium on 4th August and the invasion began on the following day with the Battle of Liège.

Ghent was to the northwest of the direct path of invading forces in the initial phase of the conflict and so had a breathing space of a few weeks as the towns and cities to the east and south fell to the invading forces. However, between the end of August and the middle of October, some 45,000 refugees arrived in the city, fleeing from the invasion and the atrocities visited upon the Belgian civilian population in what became known as the Rape of Belgium. This was not polemical propaganda: 6,000 Belgians were killed, 17,700 died during expulsion, deportation, imprisonment, or death sentence by court, and 3,000 Belgian civilians were killed by the electric fences erected by the German Army to prevent civilians from fleeing the country. Around 120,000 became forced labourers, with half of that number deported to Germany. German troops arrived in Ghent on October 12th 1914, and it was reported that Albert was one of the last British citizens to get out of the city. This is born out in his identity papers,10 issued on 10th October 1914. These include a testimonial that seems to be written with future military service in mind but couched in language which would not compromise him if apprehended by the invading forces:

‘The Bourgmestre [Mayor] of the city of Ghent certifies that Mr Beaumont Edward is a British subject, that he is a perfect gentleman and that he would be of service as interpreter.’

‘It is not generally known that Mr. Beaumont was the victim of an unpleasant incident when offering his services to the Royal Irish Rifles—he was arrested as a probable German. Perhaps the accent he had acquired abroad was the source of the trouble, but he was nevertheless detained for some time and would have continued in a seemingly inescapable difficulty had not a letter from his father contained sentences of acquiescence in his determination to enlist immediately.’12

Once this mistake had been rectified, he joined the 1/18th (County of London) Battalion (London Irish Rifles). Again, we turn to his father’s letter to College: ‘With his Battalion he was sent to France about April 1915. For two months he was fighting in the trenches’. He had, in fact, travelled from billets in St. Albans to Southampton by train on 9th March, where the Battalion embarked on four ships: the Queen Alexandra, Copenhagen, Trafford Hall and Viper. They landed at Le Havre at 9.30am the following morning and were moved to a camp five miles from the port. On 12th March they were transported by train 140 miles northeast to Winnezeele, 15 miles inland from Dunkirk. A further move one week later took them to Burbure, 10 miles west of Béthune, where they were to be billeted for the remainder of the month, spending the time training. During April and May, Albert’s short war experience would be played out in the Béthune sector, spending June 8 miles southeast near Loos/Lens.

Béthune in January 1915. The city was largely still intact when Albert and the London Irish Rifles arrived, but was not destined to escape destruction. Copyright IWM Q57407.

By the end of March, Albert’s linguistic skills had been recognised. He wrote home to his father who forwarded it to the local paper. It was published on April 3rd and details show it was written on March 24th at Burbure. The text is worthy of reproducing in full as it not only gives a picture of his situation but gives a sense of the measure of the man:

‘AT THE FRONT — A BOURNEMOUTH YOUNG MAN’S EXPERIENCES

‘Mr. W Beaumont, of 13, Sedgley Road, Winton, has received a letter from his son, Mr. E Beaumont, who is at the front with the British Expeditionary Force, in which he says: “I hope that you received my letter of a few days ago. Since writing it we have made two moves and I have been very busy. I am, I believe, on the upward grade, being recognised as official interpreter of my double company. When we move I go with the advance party to fix up billets for about 250 men. We sleep in barns, outhouses and private houses. The country we are in is purely mining and agricultural, and the people are poor, but their hearts are as large as the barns we sleep in. They are good to us. On the whole the life is absolutely a man’s life—hard and healthy and for a time it is good. We all view our former state of living from a point far distant from it, and the more thoughtful of us see where we have failed and where, if God spares us, we can do better. I have never had it brought home more forcibly the value of time and opportunity, and I am certain that those of us who survive this ordeal will emerge stiffened in mind and body. It is wonderful to see how temperate the fellows are. I have not yet seen a drunken soldier since I have been here with them. On the other hand the language is more lurid, but that will wear off after the war. Personally I am suffering from a lack of mental occupation. When I think of my little library at Ghent, and my piano and music, it makes me wish to get out of it for a short time and forget the war.

“I have had time to study officers and men under new conditions of life. Almost without exception they are good. There are a few of the former obviously too young to lead men and lacking in tact and the necessary experience in handling men, but taking them as a whole they are decent lot of men who will not fail us. My captain has promised to take me before the colonel so that in my next letter I may have good news for you. I have plenty of friends among the men, seeing that I interpret for them all. They find me jolly useful, and it is a pleasure to serve them even in this minor capacity. In the evening I go to the various public-houses with the pickets to see that the military regulations are carried out. That is an interesting if unremunerative occupation. The open-air service last Sunday was very impressive. The hymns and the National Anthem rolled out magnificently, while in the distance an aeroplane (German) was being fired upon and we could see the shells bursting around, the smoke being like small puffs of cotton wool.13

“Sir John French14 reviewed us the day before yesterday. He was pleased with us. You have heard the full story of Neuve Chapelle. What must the fellows left in England think when they read of our heroes out here. I esteem it an honour above all price to be allowed to take part in this war and count myself the luckiest of mortals to be here. All honour to those here, and may the slackers left behind feel the shame a thousandfold for not doing their duty.”’

No doubt part of Albert’s moral imperative was informed by his Ghent experiences and the refugees he would have come across there.

Details of the Battalion’s movements and actions are recorded in the London Irish Rifles War Diary. The handwriting in the early part of this period is very difficult to read and unusually unfocused: it contains a lot of extraneous material on other units, making for a confused picture. The overall pattern is of his Battalion alternating with the 20th Battalion London Regiment, and of life rotating through rest days, training, and deployment in the trenches, where they suffered shelling.

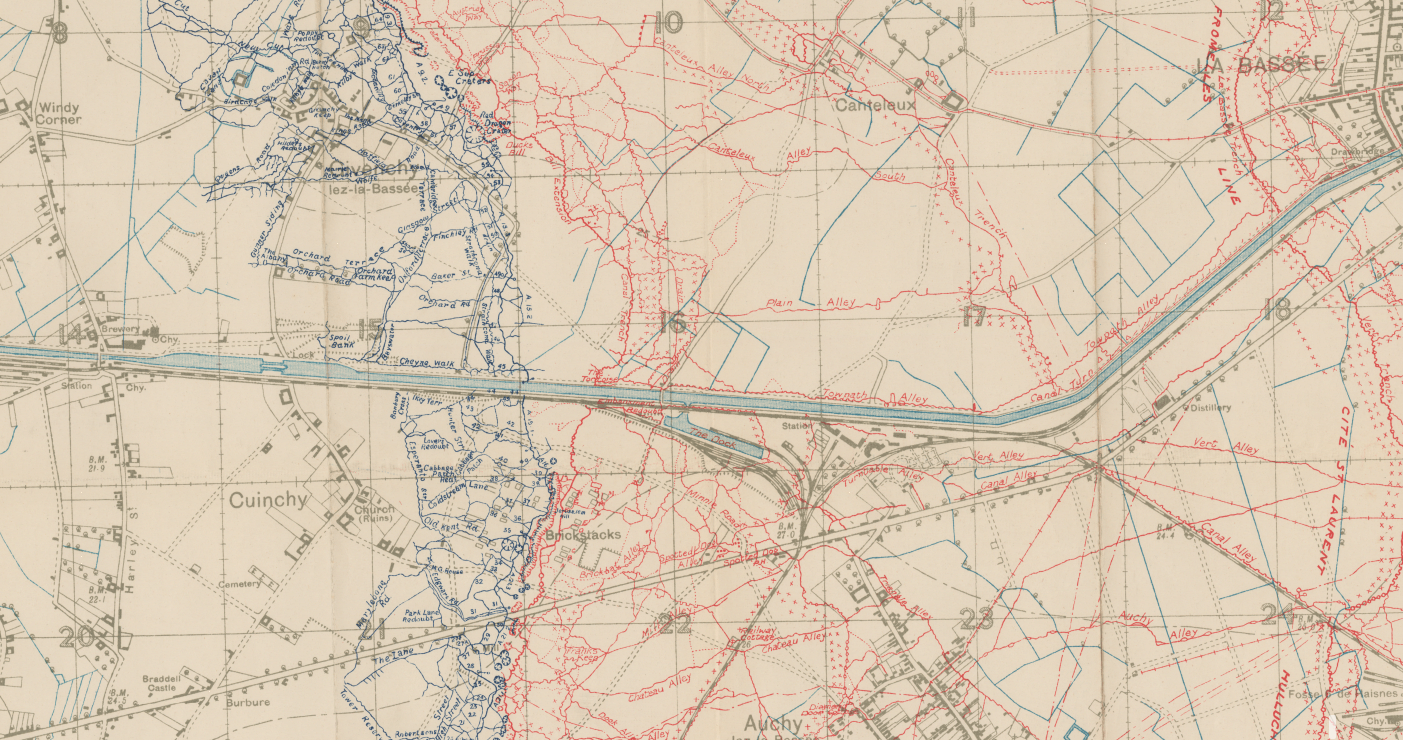

The Battalion’s first taste of action came as they moved into the city of Béthune on April 7th. The buildings, which were to be almost completely destroyed in the German offensive of Spring 1918 were, at this stage, largely intact, though the billets provided for the men were ‘somewhat knocked about—very little glass in the windows.’ This was to be their base and HQ while the four Companies moved out to trenches at Annequin and the La Bassée Road on rotation. The Battalion was attached to the 6th Brigade from this day. The men began working parties around the village of Cuinchy and suffered their first casualties: 2 Riflemen slightly wounded by shelling.

The coming days were spent in a number of moves around the area to the east and northeast of Béthune, with the men manning front line trenches or in reserve: Gorre and Festubert (April 18th to May 5th), La Beuvriere, Les Glaugmes, Les Façons, Le Touret, Givenchy (May 6th-18th). It is difficult to know to what extent Albert would have been involved in any front-line work as at some point he became part of the HQ staff as an interpreter.15 His father’s letter to the College would suggest that the change took place in early June.16 The Battalion HQ moved with the Battalion, so he would never be far from the action.

The map shows a small section of the Cuinchy/Givenchy area; Bèthune is 4 miles to the west. Although dated two years later, the stalemate in this sector can be seen in that the trenches are in the same place as in May 1915. The Canal d’Aire à La Bassée and the main Béthune to La Basée road are prominent features. The map covers 2½ miles east to west. Enemy trenches are marked in red, British/French in blue.

Albert’s Battalion, part of the 1st Army under the charge of Field Marshal Douglas Haig, were on the southern fringe of the Battle of Festubert. At Givenchy on the 17th, the men were fortunate to escape casualties when a mine was exploded under the British trenches just north of their position. Two days later, the Battalion were moved 2 miles back from the front line to Le Préol for rest before returning to the Givenchy trenches on the 23rd. On the 25th and 26th an attack was made by other units and the Irish Rifles worked in support, suffering some casualties. An enemy trench was taken but this proved to be difficult to defend as it was overlooked by German artillery on higher ground. Attempts to hold it were protracted and expensive, continuing beyond the end of the month, when Albert and his men were pulled out for rest to billets in Bèthune and, on June 3rd, Annequin.

They were then moved south into the Loos/Lens area where they were in support trenches at Le Brebis (7th), reserve billets at Mazingarbe (11th), Le Brebis (17th), Grenay (21st, where it was reported that a number of children in the village were wounded by shelling on two occasions), and Le Brebis, near Mazingarbe (25th).

The whereabouts of Albert in the final entries leading up to his death (26th-30th June) are, on the surface, difficult to interpret. After consistently using place names throughout, the diary suddenly tells us that Albert’s Battalion moved from Le Brebis to relieve the 20th Battalion London Regiment at W3. The link between the entries of 30th June and 1st July (the latter, in a different hand, describes what is probably the same location using a different name) makes it likely that W3 was in or near Grenay/Maroc.17 A map of this area, made by a 47th Division Signals Company Royal Engineers, shows W3 to be the code for a section of the British front line lying just over one mile to the east of Grenay.

W3, 29th June: Quiet day. Slight shelling by enemy but no damage done. Work commenced in B Line.

W3, 30th June: Enemy shelled Battalion HQ and neighbourhood with High Explosive shell. 4 Casualties. Considerable damage done to North Observation Station. Work in B Line continued.

Maroc, July 1st: Enemy shelled neighbourhood HQ at intervals throughout the day, only damage done to North Observation Station. Work continued in B Line and repairs to Observation Station.

Albert, acting as interpreter at HQ was among the casualties.

It is not known if he received his mortal wound on the 30th, as noted in the war diary, or July 1st as stated in his father’s letter. He died in a Field Hospital in Mazingarbe on July 2nd and was buried at Mazingarbe Communal Cemetery, in Grave Number 97. It is a small cemetery with only 108 burials. His headstone carries the words of Christ from John’s Gospel, Chapter 15 Verse 13, chosen by his father:

Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.

Original researcher and author: John Westwood. Revised and augmented by John Vickers

Footnotes

- 1901 figures. Bournemouth Daily Echo – Saturday 26 January 1901, p3

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- This should read C.L. Burrows. Rev. Clement Larcom Burrows M.A. (1858-1915)

- Bournemouth Daily Echo – Tuesday 9 September 1902, p3

- Hampshire Record Office 47M91W-Q4-2 Recollections of College life 1892-1937 – W.Smoker

- The Wintonian, List of Winchester Men 1904-1905

- Bournemouth Guardian – Saturday 10 July 1915, p4

- Bournemouth Graphic Friday 9 July 1915, p7

- Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer – Monday 26 July 1915 p3

- Bournemouth Graphic Friday 09 July 1915 p7

- The Battalion Diary for Sunday 21st March records: ‘Church Parade—Hostile aeroplane observed over LILLIERS—two bombs dropped.’

- Field Marshal John Denton Pinkstone French, 1st Earl of Ypres, KP, GCB, OM, GCVO, KCMG, ADC, PC (28 September 1852 – 22 May 1925). He was forced to resign as Commander in Chief of the British Expeditionary Force after questions were raised about his leadership. He did so on December 6th 1915 and was replaced on December 18th by Field Marshal Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig, KT, GCB, OM, GCVO, KCIE (19 June 1861 – 29 January 1928).

- Obituaries, Bournemouth Guardian – Saturday 10 July 1915 p4 and Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer – Monday 26 July 1915 p3

- ‘For two months he was fighting in the trenches, and afterwards appointed official interpreter to his Battalion, and was stationed at Headquarters.’

- Usually this would be seen as a map reference but in this case it cannot be so as the only W3 map references are either behind German lines or at least 10 miles from the front line, and the diary specifically says that it is a front line location. The 20th London diary for the corresponding dates, is written the same way: consistent place names then W3.

- Bournemouth Guardian – Saturday 10 July 1915, p4

- Ibid., and Western Gazette – Friday 9 July 1915, p2

Sources

Britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. (2019). Register | British Newspaper Archive. [online] Available at: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000638/19020909/057/0003 [Accessed 26 Apr. 2019].

Britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. (2019). Register | British Newspaper Archive. [online] Available at: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000638/19010126/065/0003 [Accessed 26 Apr. 2019].

Britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. (2019). Register | British Newspaper Archive. [online] Available at: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0002177/19150710/078/0004 [Accessed 26 Apr. 2019].

Britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. (2019). Register | British Newspaper Archive. [online] Available at: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0002173/19150709/050/0007 [Accessed 26 Apr. 2019].

Britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. (2019). Register | British Newspaper Archive. [online] Available at: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000687/19150726/067/0003 [Accessed 26 Apr. 2019].

Britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. (2019). Register | British Newspaper Archive. [online] Available at: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0002177/19150403/075/0005 [Accessed 26 Apr. 2019].

Britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. (2019). Register | British Newspaper Archive. [online] Available at: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000407/19150709/006/0002 [Accessed 26 Apr. 2019].

Commonwealth War Graves Commission, (2018). Home page. [online] Available at www.cwgc.org/ [Accessed 2018].

The Long Long Trail, (2018). Welcome to the long long trail. [online] Available at http://www.longlongtrail.co.uk/ [Accessed 2018].

Rose, M. (1981) A history of King Alfred’s College, Winchester 1840-1980. London: Phillimore.

Vickers, J. The University of Winchester Chapel Memorial Rail image.

| University of Winchester Archive – Hampshire Record Office | ||

| Reference code | Record | |

| 47M91W/ | P2/4 | The Wintonian 1899-1900 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/5 | The Wintonian 1901-1902 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/6 | The Wintonian 1903-1904 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/7 | The Wintonian 1904-1906 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/8 | The Wintonian 1905-1907 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/10 | The Wintonian 1908-1910 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/11 | The Wintonian 1910-1914 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/12 | The Wintonian 1920-1925 |

| 47M91W/ | D1/2 | The Student Register |

| 47M91W/ | S5//5/10 | Photograph of 5 alumni in Mesopotamia |

| 47M91W/ | Q3/6 | A Khaki Diary |

| 47M91W/ | B1/2 | Reports of Training College 1913-1914 |

| 47M91W/ | Q1/5 | Report and Balance Sheets 1904- 1949 |

| 47M91W/ | R2/5 | History of the Volunteers Company 1910 |

| 47M91W/ | L1/2 | College Rules 1920 |

| Hampshire Record Office archive | ||

| 71M88W/6 | List of Prisoners at Kut | |

| 55M81W/PJ1 | Managers’ Minute Book 1876-1903 | |

| All material referenced as 47M91W/ is the copyright of The University of Winchester. Permission to reproduce photographs and other material for this narrative has been agreed by the University and Hampshire Record Office. | ||