2nd Lieutenant Charles Lawes Ross, 390833 of the London Regiment, 9th (County of London) Battalion, (Queen Victoria’s Rifles), was killed in action on 12th July, 1917 near Havringcourt, France.

An International Family

Charles, known informally as Don, inherited his middle name of Lawes from his mother, Elizabeth Lawes (born 1866 in Aldershot). This side of the family were all Hampshire people at least as far back as his great grandfather in the 1780s. They were from the northeast of the county: the settlements of Basingstoke, Odiham, Crondall and, particularly, Aldershot, make frequent appearances in the family tree.

In contrast, his father’s roots and those of his forebears were widely scattered, as were his siblings’. The Ross family were originally from Scotland; his grandparents David and Ellen were born there in 1835 and 1849. David was a soldier, enlisting at the age of 18; he was a Colour Sergeant in the Rifle Brigade and, later, a Government Clerk and Chelsea Pensioner. His Army service took him overseas and it was in Canada that Charles’ father, Charles Mclean Ross, was born in Ontario in 1869. Also born there were Charles Mclean’s brother George (1871), while sisters Isabella (1873) and Amy (1875) were born in Dover and Winchester respectively.

The family’s peregrinations did not end there, for Charles Maclean also joined the Army, but as an Army Schoolmaster. On a superficial glance, the main records show a settled existence in the garrison town of Aldershot: it was there that he met and married Minnie Lawes (married April 7th, 1890 at St Michael the Archangel Church, pictured), and it is where they appear through the subsequent censuses in 1891, 1901, and 1911. However, the birth records of their three children tell a different story: although Charles Lawes was born in 1891 in Aldershot, his brothers were not. Roy Mclean was born in 1895 at Norwich and Robert Hector David in 1900 in Aden.1

The moves must have made for a disrupted home and school life, with the additional painful breaking of childhood friendships. As they grew up, Charles and Roy would follow their father into the teaching profession, while a professional Army career beckoned for Robert.

Charles’ later college Student Record carries details of his schooling. He attended military schools in Karachi, Quetta and Aden, before completing his education at West End Boys’ School, Aldershot. At the age of 16 he continued at the same school as a pupil teacher for one year, and then became an uncertified assistant teacher for a further year, still at West End Boys’. In this final year, he sat and passed the Preliminary Examination for the Certificate, and did so handsomely, gaining distinctions in English Language, English Literature, History, and Geography. The qualification allowed him to apply for a place at teacher training college and his choice was Winchester.

Winchester Training College, 1909–1911

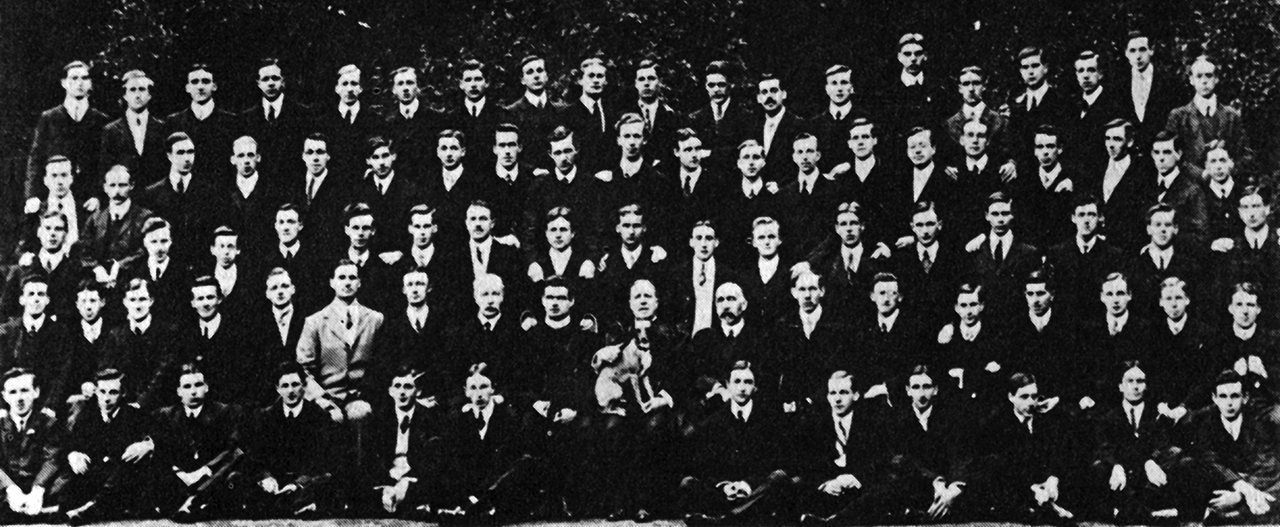

Charles must have been a diligent and gifted scholar to secure a place at College and he started studying there at the age of 18—the minimum age for entry. In his second year he appears on the College census return as one of the seventy-nine students, with the principal Henry Martin, aged 66, named as ‘Head’. He would have had an immediate rapport with Principal Martin’s wife, Frances (36), who was born in Aden where Charles had lived for a while around the age of nine.

The census sheets themselves read as a reminder of the full College Memorial Roll; no fewer than eight of this cohort would fall in the Great War. Those whom Charles rubbed shoulders with were:

In the student publication, The Wintonian, one of his compositions made its way into print. Probably written not long after his arrival, it looks with humour at the relationship between the new first year students (juniors) and the final, second years (seniors):

A Proposal

O! Second year so great and high,

To whom the first Year are as dust,

Who to the Juniors do cry

Do thou our will, thou shalt and must!Remember how in days of yore,

Before thou wast of high degree,

Thou didst with dread and trembling awe

Look on a Senior’s Majesty.Remember how, with shaking fear,

Thou didst behold the mighty man,

Didst brighten at his words of cheer,

Or quail beneath his awful ban,Remember this, and let thy heart

Be filled with pity for our plight,

And let it be thy gracious part

To guide us in the paths of right.If we by chance traditions break,

Or disregard some ancient rule,

No ruthless vengeance on us take,

For we are new to Winton’s school.If we should carol in the Dorm,

Or whistle in a cheerful pitch,

Or break some other Rule or Form

In Hall, or Corridor, or Ditch,

Look on our mirth with lenient eye,

And tell us gently of our error.

Then rest assured that we will try

To do the right through joy, not terror.United with one heart and hand,

The strong shall help the weaker brother,

And Winton’s fame throughout the land

Shall ne’er be equalled by another.

Charles became sub-editor of The Wintonian magazine and, of course, good form would dictate that he would feature less under his own pen. The only other thing we glean from its pages is that he was awarded his swimming medallion.

Despite his undoubted literary abilities and some excellent academic results before entry into college, Charles seems to have struggled with some parts of his college work. While he scored highly in some subjects and was mid-range in many, overall results left him languishing towards the bottom of his year group. He struggled in technical subjects: science, geometry, algebra and arithmetic, and these dragged down his average scores.

Until 1908 it was mandatory for students to join the college Volunteer Company but the national change of all Volunteer units to Territorial led to college requiring students to elect to sign up since the new system placed much more stringent responsibilities on the men. It is not known whether he joined the College Territorial B Company in which many of the students served during their studies.

At the successful completion of his course he left to teach, back again at West End Boys’ School. The West End Schools were divided into three: Infants, Boys, and Girls. They backed onto the Municipal Gardens and, when built in 1873, had accommodation for 375 boys and 300 girls, with a drill hall as part of the Boys School. The schools had been enlarged in 1878 and again in 1883. By 1911 school numbers were 1,332. Charles would have taught under the headmaster Mr. Gregory.2 ‘Drilling’ was included in the boys’ school timetable and two hours a week was set aside for that purpose. An ex-Army Sergeant gymnast was appointed for this class at a rate of 2/6d. per lesson.

Charles and his younger brother Roy were also Assistant Scout Masters at 4th Aldershot West End Boys School scouts. He is listed in their Book of Remembrance and the troop still possess the Don Ross trophy.3

Also in 1911, we find that Charles’ brother Roy had begun to train for the teaching profession.4

At War

Charles Lawes wasted little time in enlisting in the Army. He signed up to serve in the Autumn of 1914 at a London recruiting centre and was placed in the 2/9th Battalion London Regiment (Queen Victoria Rifles).

The Battalion was formed in London in August 1914, though it is unclear if Charles was there at its inception: his War Gratuity upon death would suggest an enlistment date of around October 1914. The Battalion moved to Crowborough, Sussex, in November, where they were placed under orders of 2/2nd London Brigade. Further moves were to Ipswich, in June 1915, Bromeswell Heath, Suffolk, in May 1916 and then to Longbridge Deverell, Wiltshire, in July.

While Charles was still safe in Ipswich, things were quite different for his brother Roy at this time. Unbeknown to Charles, at 5.50am on 25th September, 1915, Roy and the men of the 1/14th Battalion London Regiment (London Scottish) were going over the top in a full offensive at Vermelles. His Battalion were acting as a link between two Divisions on either side, advancing on a broad front towards enemy lines. They were to walk into a hail of machine-gun and rifle fire and find the barbed wire entanglements uncut by the artillery barrage—the nightmare scenario for all front-line men. Their total annihilation was only averted by the unexpected surrender of the 600 Germans in their sector of the enemy trench. Nevertheless, the War Diary stated, towards the end of the action, that ‘up to this time our casualties amount to 40%’. Roy was one of those who had given his life in service of King and country, although at first his demise was uncertain. There were reports that he had been found by stretcher-bearers but one week later his parents were informed in a letter written by chaplain Rev. R. A. Stewart that he had indeed fallen on November 3rd. His body was retrieved but subsequently lost in further fighting in the locality.

After so many moves around military camps, the next move for Charles and the 2/9th Queen Victoria Rifles was the one that they had all been waiting for. We can pick up the story from the Battalion War Diaries:

At 1am on Sunday, 4th February, 1917, the Battalion landed at Le Havre onboard the transport ship La Marguerite. The next days were spent marching, in billets, in trains and at training grounds. A litany of names announce the procession of the men towards the Somme through February: Auxi-le-Chateâu, Wavens, Sus-St-leger, Burles, Bienvillers, Burles, Bienvillers, Gernas, Hénu, Grenas, Guadiempré, Rivière, Wailly.

March 1st was their introduction to trench life, in Sector F1, in the Pas de Calais/Somme region. Much of the time through the month was spent in cycles of occupying trenches followed by relief to billets and work details making-good roads and defences, and then back to trenches. The Battalion Diary is terse and lacks casualty figures, so it is difficult to gain a sense of the threat level faced by the men.

Work was varied in April, with no combative action in the month. Following yet more moves westward, they fetched up near the Somme city of Bapaume,5 parties of men worked under the Mayor of Miraumont with others working on a railway at Achiet-le-Grand.

The men were back to front-line service on 6th May, southeast of Lagnicourt and, in a sunken road, sustained casualties: 3 killed and 13 wounded. After cycles of relieving other units and in-turn being relieved, on May 15th the Battalion was marched the three miles or so to Bihucourt where they spent 8 days training. They were back in front-line service again on 22nd May at Bullecourt where one officer and eighteen other ranks were casualties. After eight days of training the men were back there on 3rd June. A period of front-line inactivity followed, marked only by two German prisoners taken on the 12th: ‘Both tired of the war and given themselves up’. Two days later the Battalion was relieved and marched to a camp at Mory. There then came a longer respite for the men: days of cleaning, re-equipping, parades and training.

Charles and the men of the 2/9th Battalion were moved by train to Havrincourt on the evening of July 7th. The following day was spent forming up and moving each of the four companies into their correct locations in readiness to move up to the front line: B Company to the right, C Company to the centre and D Company to the left. A Company was to act as a Reserve. The 9th was occupied in moving to the front line. The following day each of the three front-line companies put out patrols, most probably at night, and this was repeated on the 11th. There was an incident on one of these patrols when C Company met a German unit and one man was wounded.6 The next day Charles met his death. It is not recorded in the diary, but the details are preserved for us in an obituary:7

Don had written home on the day he died, referring to a trench raid he took part in the night before. He was killed by a shell whilst working in front of the trench.

As work in front of a trench was always carried out only when dark, as were the patrols in no-man’s land, it is presumed that he was killed while working at night working on improving defences.

Charles is buried at Metz-en-Couture Communal Cemetery, British Extension, Département du Pas-de-Calais, Nord-Pas-de-Calais, France. He is also remembered on the war memorials at Holy Trinity and St Michael’s churches in Aldershot.

Researcher and Author: John Vickers

Sources

For all general Winchester Training College records please see the list of University of Winchester sources at the end of the following Sources list.

Aldershot History Group (2018). West End Schools, Queens Road. [online] Available at: https://www.aldershothistorysociety.com/

west-end-schools [Accessed 2018].

Ancestry (2018). Home page. [online] Available at: www.ancestry.co.uk [Accessed 2018].

Commonwealth War Graves Commission, (2018). Home page. [online] Available at www.cwgc.org/ [Accessed 2018].

Imperial War Museum (2018). Men of the 11th Battalion, Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers in a captured German communications trench near Havrincourt during the Battle of Cambrai, November 1917, Q 3187. [online] Available at: https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/

item/object/205213168 [Accessed 2018].

Issuu (2016). Rushmoor Roll of Honour 2016. [online] Available at: https://issuu.com/rushmoor/docs/

rushmoor_roll_of_honour_2016 [Accessed 27 February, 2018].

Kelly’s Directory (1911). Kelly’s Directory of Hampshire, Wiltshire, Dorsetshire, The Isle of Wight and the Channel Islands, 1911. [online] Available at: http://specialcollections.le.ac.uk/

cdm/ref/collection/p16445coll4/

id/8904 [Accessed 2018].

National Union of Teachers. (1920). War Record 1914“1919. A Short Account of Duty and Work Accomplished During the War. London: NUT.

Rose, M. (1981). A history of King Alfred’s College, Winchester 1840-1980. London: Phillimore.

Vickers, J. University of Winchester Chapel Memorial Rail image.

Wikimedia (2014). File:Aldershot Parish Church.jpg Derivative work: desaturated and sepia filter applied, John Vickers 2018. [online] Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

wiki/File:Aldershot_Parish_Church.jpg. [Accessed 2018].

University of Winchester Archive at Hampshire Record Office

All the following documents are general background resources for the WTC Fallen project and provide general period background of students, college life, staff, activities, etc. The Finding Numbers are given to aid archive searches.

47M91W/P2/4 The Wintonian 1899-1900

47M91W/P2/5 The Wintonian 1901-1902

47M91W/P2/6 The Wintonian 1903-1904

47M91W/P2/7 The Wintonian 1904-1906

47M91W/P2/8 The Wintonian 1905-1907

47M91W/P2/10 The Wintonian 1908-1910

47M91W/P2/11 The Wintonian 1910-1914

47M91W/P2/12 The Wintonian 1920-1925

47M91W/D1/2 The Student Register

47M91W/S5/5/10 Photograph of 5 alumni in Mesopotamia

47M91W/Q3/6 A Khaki Diary

47M91W/B1/2 Reports of Training College 1913-1914

47M91W/Q1/5 Report and Balance Sheets 1904- 1949

47M91W/R2/5 History of the Volunteers Company 1910

47M91W/L1/2 College Rules 1920

55M81W/PJ1 Managers’ Minute Book 1876-1903

71M88W/6 List of Prisoners at Kut

All material referenced as 47M91W/ is the copyright of The University of Winchester. Permission to reproduce photographs and other material for this narrative has been agreed by the University and Hampshire Record Office.

- Aden was at this time, and until 1935, a Colony of the United Kingdom, governed as part of British India, under the jurisdiction of Bombay. It is now in Yemen.

- Kelly’s Directory of Hampshire, Wiltshire, Dorsetshire, The Isle of Wight and the Channel Islands, 1911, p.23 and Aldershot History Society https://www.aldershothistorysociety.

com/west-end-schools - Presented to the group by his parents in 1925

- Information from the 1911 Census where his occupation is given as ‘Student (for teaching profession)‘. Charles Mclean Ross, head of the household, is recorded with a much-changed occupation: he is a Cycle and Motor Dealer‘

- Bapaume was occupied by the Germans on 26th September 1914, then captured by the British on 17th March 1917. On 24th March 1918, the Germans took the city again

- It was a non-commissioned officer and, very unusually especially in such an economical diary, the name is given: Sergeant Bennett

- Rushmoor Roll of Honour 2016