Ernest John Harland

Sergeant Ernest John Harland, Service Number 3317 was a member of the Honourable Artillery Company, Second Battalion (Infantry,) when he was killed in action 9th October 1917, during the third battle of Ypres, Passchendaele.

Family Background

Ernest came from a line of military forebears. His grandfather, John Godfrey Bartholomew Harland (1809-1868) had joined the 11th Hussars on 21st September 1829 as a young man. In his early years of service, he would experience the harsh conditions of army life in India. It was there he met and married 14-year-old1 Ann Gregory (1822-1887), on 4th May 1836 in Meerut, near Delhi. Ernest’s father, Frederick Godfrey, was born in nearby Cawnpore2 in 1838. Disease was rife, and John and his family were lucky to return to Britain very shortly after Frederick’s birth: half of the Regiment had succumbed and died in India.

The Landing of Prince Albert at Dover, 6th February, 1840. Engraving after William Adolphus Knell (c. 1808-1875)

On return, the 11th Hussars were brought back up to strength and re-equipped with the best horses and newest percussion carbines, becoming a showcase unit. John would have been one of those chosen to escort the young Prince Albert from Dover to Canterbury when he arrived in England in early 1840 to marry Queen Victoria. Impressed by their dash and efficiency, he adopted them as his own Regiment and Victoria ordered that they henceforth be known as 11th (Prince Albert’s Own) Hussars. Frederick appears in the 1841 Census, living in the 11th Hussar’s Hounslow Cavalry Barracks at Isleworth. Listed separately, but within the barracks, are Frederick (4), Emma (1) and Ann (recorded as 15, although her actual age was 193).

11th Hussar in Crimea, 1855. Copyright National Army Museum NAM. 1968-10-73-15 All rights reserved

The pattern set by Ernest’s grandfather was set to repeat with his father (Frederick Godfrey, 1838-1895). Having been brought up in the barracks, he joined the 11th Hussars at the age of 16, progressed to the rank of Sergeant and was later described as a Bandmaster. In the Crimean War of the 1850s he would have seen action in the infamous Charge of the Light Brigade (1854)—coincidentally alongside the grandfather of another Winchester Training College casualty of the Great War, R.J.C. Ferguson, who was in the 4th Light Dragoons. Frederick married Chelsea-born Elizabeth Caroline McKenzie (1844-1933) in Dublin on 17th April 1865. The first of their ten children was born soon afterwards. Two of the children died in childhood; as the UK registers do not show any other children born to Elizabeth, it must be assumed that the missing children were born and died during their time in India. Ernest was the youngest of the family:

Caroline Emmeline (b. 1866, York)

Frederick William Godfrey (b. 1869 Muttra, India)

Charles Henry (b. 1872, Muttra, India)

Ada Louise (b. 1876, East Molesey, Surrey)

Elizabeth Florence (b.1878, East Molesey, Surrey)

Annie Louisa (b. 1880, East Molesey, Surrey)

Amy Beatrice (b. 1883, East Molesey, Surrey)

Ernest John (b. 14th April 1886, East Molesey, Surrey)

After his retirement from the Army in 1876, Ernest’s father worked as a warder at Hampton Court Palace and was a Chelsea Pensioner. Professional soldiering was perpetuated in the new Harland generation by Ernest’s brother, Frederick William, who enlisted in the Royal Engineers in 1887.

Unfortunately, military service wasn’t the only common thread in the family’s history. On October 10th 1893, at the age of 56, Frederick senior was admitted to Brookwood and Holloway Mental Hospital on the order of a local Justice of the Peace and a doctor. The hospital Admissions Register reports that he had been suffering from dementia for two days before admission. He was discharged after nine weeks but whatever relief had been gained was short lived. He was readmitted on August 10th, 1894 after experiencing dementia over a three-week period. He was to die in the hospital the following July. These must have been difficult times for Ernest, still at elementary school. More traumatic for his mother Elizabeth, was the reappearance of mental illness in the family only five years later. Frederick junior’s career in the Royal Engineers, serving in Cape Colony, Orange Free State and Transvaal, was cut short. A brief note in his Army record reads, ‘Tried by District Court Martial 16th November 1901 and reduced [from Sergeant] to Sapper for embezzlement. Discharged as a lunatic 25th March 1902.’ It is unclear if the mental incapacity was a factor in his committing the offence, or the corollary of the Court Martial.

Subsequent records would suggest his illness was temporary. He was initiated as a Freemason into the Sheerness United Service Lodge (No. 3124) in January 1906, his military service is stated as late Sergt. R.E.—suggesting a degree of dissimulation. He was at this time living at The Watermans Arms, Sheerness, as landlord of the pub (see image). He later became landlord of the Duke of Clarence pub in the town, his brother Charles taking over the Watermans Arms from him.4

Frederick at the Waterman’s Arms, Sheerness

From 1876 onward, the family lived in Ernest Cottage in Park Road, East Molesey. Following Frederick senior’s death, the family had been able to afford to keep the house on. The 1901 Census5 shows that the 54-year-old widowed Caroline was ‘living on own means.’ She had received £131 from the estate of Frederick and would have had a small pension from the Army; it is likely therefore that she had some invested capital of her own. Of the children, only Ada (a dressmaker, 24), Lily (Elizabeth, a school teacher, 22), Amy (no occupation listed, 18) and Ernest (at school, 14) are still at home. By 1911 Amy had married and left home, leaving Ernest with his two sisters. By this time both Ernest and Elisabeth were Certificated Teachers working for the County Council; however currently we have no evidence to show where Elizabeth completed her teacher training.6

East Molesey and Hampton Court Bridge, circa 1900. Ernest’s father would have walked to work across this bridge each day. The family home was about half a mile from the bridge, off-picture to the right. Copyright unknown.

Ernest and Teaching

Ernest had begun his own education at East Molesey National School. The National Schools were run by the National Society for Promoting Religious Education and aimed to provide elementary education, in accordance with the teaching of the Church of England, to the children of the poor. Ernest’s school was on two sites within the village of East Molesey: the girls’ and infants’ school about 400 yards away from the boys’. Ernest had to walk only a few doors down Park Road to attend. The school, led by headmaster George Wright, was oversubscribed, having places for 150 boys but average attendance of 160.7 He remained there as a pupil-teacher.

Life as a pupil-teacher is frequently referred to as arduous. In addition to classroom work in very large classes, there was training before and after school each day with the headteacher, evening classes and often Saturday mornings at a pupil-teacher training centre. There were other challenges that came with responsibility at a young age, as Ernest’s sister Elizabeth was to find to her cost. This from Surrey Comet of Saturday 10 October 1896:

A PUPIL TEACHER ASSAULTED

Mrs. Albert Smith, of 22, Avern-road, East Molesey, was summoned for assaulting Lillie Harland on the 1st Oct.

Mr. G Washington Fox, solicitor, appeared for the complainant and stated that she was a pupil teacher at East Molesey national Schools. Defendant’s two daughters attended the schools, and on 1st Oct. defendant came to the school and enquired for Lillie Harland. As soon as the complainant presented herself, and without any explanation, defendant dealt her a hard stunning blow, at the same time stating that it was for striking her child, and if ever complainant struck her child again she (defendant) WOULD STRIKE HER HARDER. There was, of course, no truth whatever in the statement that the defendant had struck the child at all. As a matter of fact corporal punishment was rarely inflicted at those schools, and if so it was only inflicted by the head mistress. He need hardly tell the Bench that pupil teachers had not too rosy an existence at any time and it would be a monstrous thing if conduct of the kind complained of were allowed to go unchecked and unpunished. There would be an end to all discipline in the schools. He therefore asked the Bench to inflict a punishment severe enough to meet the exigencies of the case.

Complainant, who lives at Ernest Villas, Park-road, East Molesey, said defendant sent two children—Fanny and Charlotte Smith—to the school, and having asked to see witness she took her outside and without any warning struck her on the left side of her face with her open hand. She then said ‘That is for striking my child.’ Witness told her she had not struck her child, and sent for the head mistress. Defendant continued to abuse and threaten her, and said if witness struck her child again she would strike her harder still. In answer to defendant witness denied having ever struck her child.

Defendant admitted the offence, said her daughter came home and complained of Miss Harland having struck her, and in her anger she (Mrs. Smith) went to the school and committed the assault. She was ver sorry for her conduct now.

The Chairman said such conduct was most unwarrantable, and they had decided to inflict a fine of £1 and 12s. 6d. costs.

On the application of defendant time was allowed in which to pay the fine.

In preparation for applying to a training college he had taken various courses and examinations in physiography, and freehand, model and blackboard drawing. He took the entrance exam for Winchester Training College in December 1904, gaining a first-class pass. Students were also required to take the Archbishops’ Entrance Examination in which he did not do so well, achieving only a third-class pass.

During 1904 and 1905 Ernest played football for Molesey St. Paul’s. His work as a back seems to have been appreciated, judging by reports in the local press. This is one of his accolades from a game against Hampton Wick on 4th March 1905: ‘After a capital display of back work by Harland and Stott, the whistle blew and Molesey ran out winners by three goals to one’8

Winchester Training College

Ernest attended Winchester Training College from 1905 to 1907. The Surrey Comet, published on Saturday 4th March 1905, reported that Ernest had obtained a first-class entrance scholarship to the College. We know little personal detail of his life at college as his name does not appear in the college publications of the period.

Ernest’s experience of student life would have been much like this: On weekdays reveille was sounded by the bell monitor at 6.15 a.m., making his way through the dormitories, ringing a hand-bell. A cup of cocoa stood ready for students at 6.30 in the dining hall, and roll-call, taken at 6.45, was followed by an hour’s lecture. Then came morning service and afterwards breakfast at 8.30 a.m. On Mondays, Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays, lectures lasted from 9 a.m. until 12.50 p.m., with a break from 10.45-11.00 a.m. Lunch was at 1 p.m., and at 2 p.m. on the above days there followed a 1–2-hour art lesson or psychology or hygiene or criticism lesson. This still left time for football, cricket, or tennis on the dytche (a sports field, lying below the main building) before tea at 5 p.m. From 7-9 p.m., commencing with roll-call, all students undertook private study in their appropriate lecture room, either junior or senior. A member of staff supervised in one room and a prefect in the other. Evening chapel was at 9.15 p.m., followed by supper at 9.30 p.m. then to bed, with lights out at 10.30 p.m.

Very much part of student life was the Hampshire Regiment. Until 19089 it was expected that every student would become part of the Volunteer Company, and with them Ernest would receive his first military training. The link with the College went back to 1859 and in 1875 the Company was officially called ‘The Winchester Diocesan Training College Corps’ or the ‘24th Hants Rifle Corps’, or simply the ‘Volunteer Force’. The College had a full armoury for rifles and ammunition, and a small-bore shooting range on Teg Down.

William Smoker ARPS, who was at the College three years before Ernest, recorded his memories of the Volunteer Company ‘written in the 86th year of my life during December 1966’:

When we Juniors entered College in September 1902, the echoes of the Boer war in South Africa were still reverberating. Joining I Company was voluntary. All our year did so. The College students formed the entire I Company of the 3rd Hants Territorials. The College had its own Armoury. The Dorm of the Arkites was above it. We were served with Enfield .303 rifles and Volunteer uniforms. On the 23rd November, 1903 we were measured for new uniforms of khaki.10 In the late Autumn of 1903, Lord Roberts11 visited Winchester. The I Company formed the Guard of Honour. When he spoke from the balcony of the Guildhall, it rained in torrents

College drills of an hour each were held on Wednesday afternoons, and Saturdays at noon. One day annually, Aldershot was attended for Battalion drill. Each man for mid-day ration received a Melton Mowbray pork pie, 5/- today would not buy such a one. We were required to do a specific number of firing practices as each year, gleefully visiting the rifle range butts at either Romsey, Bramdean, Kingsclere, or Lee on Solent. The latter provided us with all the fun of the fair, for the boats were reached from Gosport on a baby railway with metals set about a foot apart, along which a minikin engine drew carriages just wide enough for a pair to sit side by side. We had several sham fights with other Companies. The Principal attended these, and was no mean tactician, and did not refrain from reprimanding us College students, for any military fault. In one sham fight, I took as prisoner, a youth of St. Mary’s College, and was made to release him with much indignation to myself.

Of the students Ernest knew in his two years of study, no fewer than ten would give their lives in the Great War.

Students took College exams at the end of the Christmas term and in midsummer. In his first set of exams Ernest was placed 17th in the order of merit, with an average grade of 69.9%. At the Christmas of his second year, Ernest was unable to take his exams due to illness. At the end of his two years of study he was graded by the College with A for Music, B for Drawing and Teaching and C for Science. He achieved a second class pass in both his certificate exam and his final Archbishops’ exam.

On leaving College, he worked for Surrey County Council as a certificated teacher. He lived at home and his College records show that he returned to the National School East. The Electoral Roll for 1912 shows the domestic arrangement: he was a lodger at Ernest Villa (the family home), had a furnished bedroom on the second floor which he rented at 10 shillings per week from his mother, who was his Landlord.

On August 2nd 1913, Ernest married Elsie Gertrude Wheatly in the Parish Church in East Molesey and they lived at Walton Villa, 50 Pemberton Road, East Molesey. They had a daughter, Audrey, who was born on 21st June 1914.

At War

He enlisted as a Private in the Honourable Artillery Company at Armoury House, Finsbury Park, on 31st March 1915, and was posted the same day. When Ernest joined it was at Orpington, then it moved to Tadworth, and then finally to the Tower of London in August 1915 to prepare for war.

The Honourable Artillery Company is the oldest regiment in the British Army, dating back to 1537 when Henry VIII granted a charter to the Fraternity or Guild of Artillery of Longbows, Crossbows and Handguns ‘for the better increase of the defence of this our realm and the maintenance of the science of artillery’. It fought in the English Civil War and sent members to the Boer War. In 1908, following army reforms, it become a Territorial Force (T.F.)—part-time soldiers. It was to send seven units to France, and some 13,000 men. The 2nd Battalion HAC fought as infantry throughout the First World War.

As the HAC was a T.F. unit, which had been established for ‘Home Service’ only. T.F. soldiers had to further volunteer for overseas service and Ernest did so on the 31st May 1915 at the Tower of London.

Promotions followed: to Lance Corporal at the beginning of August 1916 and, by the beginning of October, he had substantive promotion to Corporal, having temporarily held that rank from September 1916. Finally he reached the rank of Sergeant on the 15th May 1917. His medical inspection report from the time he enlisted tells us that Ernest was 5ft 10¾in tall, with a 36½in chest. He had perfect vision and his physical development was described as fair. He would have had a period of training and had risen in the ranks to Sergeant, prior to his arrival in France. We know that Ernest, with the HAC 2/1st battalion left Southampton for France on board the paddle steamer La Marguerite, arriving in Le Havre on the 3rd October 1916. His service record states that he proceeded to the front, near Steenwerck, on 4th October 1916.

Troop transport paddle steamer La Marguerite

The 2/1st HAC was placed under the command of 22nd Brigade in the 7th Division. Whilst in France the Division were held in reserve, as the Battle of the Somme was beginning to wind down in preparation for the winter, so were not called into the line for any major offensive. Once at the front, Ernest suffered from bouts of illness. He was first admitted to hospital in November 1916 with dysentery, followed by colitis, before being discharged back to his unit on 23rd December.

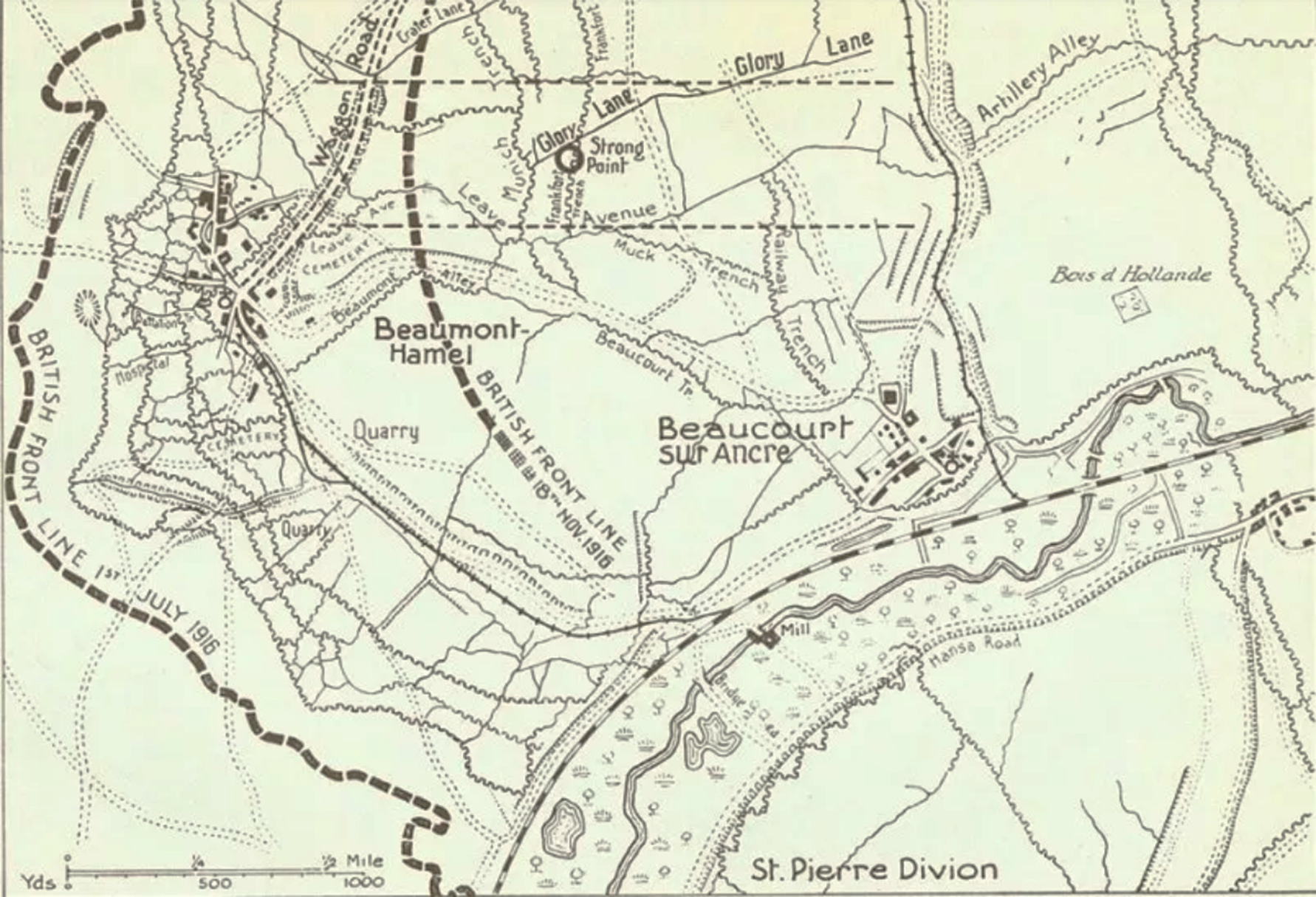

The New Year brought the 7th Division up the line and they formed part of Fanshawe’s V Corps and were involved in the operations of the Ancre. These were skirmishes to establish height advantage over the German positions; essentially they were the very last flickerings of the Somme Campaign.

7th Division were involved in the capture of the Munich Trench, 10th–11th January. The attack, by a brigade of the 7th Division, began at 5:00 a.m., when the leading companies lined up on tapes, 200–300 yds (180–270 m) from the Munich Trench. At 6:37 a.m. three divisional artilleries began a standing barrage on the trench and a creeping barrage started in no man’s land in thick fog. Movement was so difficult that the barrage moved at 100 yd (91 m) in ten minutes. German resistance was slight, except at one post where the garrison held on until 8:00 a.m. After the fog cleared at 10:30 a.m., the ground was consolidated, most of it being free from observation by the Germans.

The area around the Munich Trench, which may be seen running north–south, left of centre, top. Copyright unknown.

Operations continued in the Ancre until the end of February, with actions taking place all along the line designed to advance the Allies lines and to harass the enemy.

As the war dragged on into 1917 the 7th Division, still part of V Corps under Fanshawe, now found itself subsumed into the Fifth Army under Gough. The war was going badly for the Germans resulting in their retreat to the Hindenburg Line. They pursued a scorched earth policy, destroying what they could in order to slow down the advancing Allies.

Ernest and the rest of his battalion found themselves on the move again working northwards, arriving in the Arras sector in April. The Hindenburg Line near Bullecourt was a heavily fortified German stronghold and it became apparent that this needed to be neutralised. The first attack on Bullecourt took place in April but met with fierce resistance so essentially failed in its objectives. The Division was involved in a flanking operation at the second Battle of Bullecourt which took place in May 1917. The 7th Division along with the 62nd finally took the town on May 17th and held on to it. In August, Ernest was granted 10 days leave in the field, so he would not have been able to return home to see his wife and young daughter.

The Division retired from the line and then moved north into the Ypres sector and took part on the Battle of Polygon Wood as part of X Corps under Morland. The Allies were up against dispersed and camouflaged German defences, using shell-hole positions and pillboxes. They also held back much of their infantry for counter-attacks. This strategy meant that as British advances became weaker and disorganised by losses, fatigue, poor visibility and the channelling effect of waterlogged ground, they met more and fresher German defenders. The action became attritional as attack and counter attack developed and no overall gains were made on either side.

The operation that saw the death of Ernest was the attack on Becelaere 9th October 1917. The H.A.C. War Diary at the time states:

October 6th 1917: The 7th Division have been given the task of advancing the line now held by 21st Division in order to secure observation over the valley of the Polygone Beek and Reutel Beek and to widen the salient formed by the present Divisional front.

The 2nd HAC were to attack the village of Reutel, to the west of Becelaere. On their left were the 2nd Royal Warwickshires, with the 9th Devons as Brigade reserve. Zero hour was 0520 9th October. It had rained the week before, so the ground was sodden and the going was extremely heavy for all the advancing soldiers. Not many units managed to get to their starting points on time, some lost their way to the jumping off point and at least one officer was killed when he led his men into the path of a number of Germans.

A barrage was laid down on the enemy, and the battalion advanced only 50 yards behind it. Battalion Headquarters then appeared to lose touch with the advancing troops, and it was not until midday that it was confirmed that elements of the battalion had captured the village. Officer casualties had been so severe that no officer was present in Reutel. Interestingly, the War Diary records that ‘A’, ‘C’ and ‘D’ companies had suffered such heavy casualties that they were relieved. Records show that Ernest was a member of ‘C’ company, which had had a stiff fight for a pill-box, costing the lives of most of a platoon.

The 2/1st HAC held the village and were relieved on the 10th. During the attack, the battalion suffered 296 casualties, including fifty-six dead, one of whom was Ernest. No officer that took part in the attack was not a casualty.

His body was never found. He is remembered on the Tyne Cot Memorial to the missing.

Probate records that his widow Elsie received £254 11s 0d. She was also in receipt of a widow’s pension of 21s. 3d. a week. After his death, Elsie received a package containing Ernest’s belongings. These were: a pocket wallet, letter, photos and a lock of hair. Ernest had survived many battles in the Great War and whilst he paid the ultimate price, he followed the family military tradition.

Elsie Harland died in 1981 aged 96. She never remarried.

Researcher and Author: John Westwood, revised with additional material by John Vickers

Footnotes

[1] Her age is born-out by Indian records and all subsequent British documentation. Details of marriageable age in pre-Raj India (i.e. ruled and administered by the East India Company) for female British subjects is not known. Hindu records for the period do not exist but Catholic figures for marriage age of females (all marriages, British and indigenous) from 1830-1839 averaged 14.0 years, with the median in the 13-14 age group (sample 380. Krishnan, P. (1977). Age at marriage in a nineteenth century Indian parish. Annales de démographie historique, [online] 1977(1), pp.271-284. Available at: https://www.persee.fr/doc/adh_0066-2062_1977_num_1977_1_1353 [Accessed 18 Dec. 2018].)

[2] Cawnpore is known to many for the massacre of the British garrison, but this is still some 19 years in the future at the time of Frederick’s birth.

[3] Ages in the 1841 Census are accurate to the year for those under the age of 16. Older subjects are rounded to the nearest multiple of 5 but some enumerators consistently round up or down. Ann was 19 at this time.

[4] Both pubs were in in Blue Town, Sheerness. Blue Town was a deprived area close to the docks, which had got its name because dockyard workers had ‘liberated’ blue paint from the dockyard to paint and therefore aid the preservation of their wooden houses. Frederick junior’s working career lasted at least into his 70th year, when he was recorded as running refreshment rooms in the Isle of Sheppey (Kelly’s Directory). He died on 1st April 1948, aged 79 years.

[5] The family’s 1901 census is difficult to find as the surname is transcribed in some indexes as Hardlow.

[6]When Ernest was killed in action Army Form W.5080 was filled out giving the names and addresses of his living relatives. As well as his wife and daughter, the list also includes his mother, still living in Park Road along with her daughters Caroline, Ada, Elizabeth and Annie. Amy had married and was living in New Malden, Surrey. Ernest’s two older brothers were both living in Sheerness.

[7] Kelly’s Directory of Surrey, 1891

[8] Surrey Comet, Wednesday 8 March 1905, p8.

[9] In 1908 the Territorial Force was formed, and the Volunteer Force ceased to exist. The College Company became B Company of the 4th Territorial Battalion of the Hampshire Regiment. From now on, students at the College would no longer be enrolled, instead they would be enlisted. This changed the nature of the Force and not all students joined. The men were subject to a more professional system which included military discipline and more thorough training. (Rose)

[10] Before this, the uniform was red tunics and black trousers

[11] Field Marshal Frederick Sleigh Roberts, 1st Earl Roberts, VC, KG, KP, GCB, OM, GCSI, GCIE, KStJ, VD, PC (30 September 1832 – 14 November 1914)

Sources

Ancestry (2018). Home page. [online] Available at: www.ancestry.co.uk [Accessed 2018].

British Newspaper Archive (2018). The Surrey Comet , published on Saturday 4th March 1905, p.8. [online] Available at: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000684/19050304/139/0008 [Accessed 2018].

Commonwealth War Graves Commission, (2018). Home page. [online] Available at www.cwgc.org/ [Accessed 2018]

The Long Long Trail, (2018). Welcome to the long long trail. [online] Available at: http://www.longlongtrail.co.uk/ [Accessed 2018]

Rose, M. (1981). A history of King Alfred’s College, Winchester 1840-1980. London: Phillimore

Vickers, J. University of Winchester Chapel Memorial Rail image.

| University of Winchester Archive “ Hampshire Record Office | ||

| Reference code | Record | |

| 47M91W/ | P2/4 | The Wintonian 1899-1900 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/5 | The Wintonian 1901-1902 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/6 | The Wintonian 1903-1904 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/7 | The Wintonian 1904-1906 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/8 | The Wintonian 1905-1907 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/10 | The Wintonian 1908-1910 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/11 | The Wintonian 1910-1914 |

| 47M91W/ | P2/12 | The Wintonian 1920-1925 |

| 47M91W/ | D1/2 | The Student Register |

| 47M91W/ | S5//5/10 | Photograph of 5 alumni in Mesopotamia |

| 47M91W/ | Q3/6 | A Khaki Diary |

| 47M91W/ | B1/2 | Reports of Training College 1913-1914 |

| 47M91W/ | Q1/5 | Report and Balance Sheets 1904- 1949 |

| 47M91W/ | R2/5 | History of the Volunteers Company 1910 |

| 47M91W/ | L1/2 | College Rules 1920 |

| Hampshire Record Office archive | ||

| 71M88W/6 | List of Prisoners at Kut | |

| 55M81W/PJ1 | Managers’ Minute Book 1876-1903 | |

| All material referenced as 47M91W/ is the copyright of The University of Winchester. Permission to reproduce photographs and other material for this narrative has been agreed by the University and Hampshire Record Office. | ||